Maverick Life

Grahamstown ArtsFest ‘16: Naked in the solo spotlight

One large stage. One small human being. Hundreds of eyes and ears. Solo theatre must be the most frightening thing for an actor to perform. You’re out there on your own. There’s no safety net. The lights are on you and the theatre is silent. And you have to hold them in the palm of your hand. By TONY JACKMAN.

Flying solo, driving solo, going solo. Writing solo. You carry a weight on your shoulders when you set out to write a piece of solo theatre. The words and themes that you’re setting down have to inspire a director who will then carry an actor through an hour or more on stage. It’s no light responsibility.

Then you have to release your words, your mental blueprint of what it will look and sound like, your ear’s interpretation of how a word will be inflected, of which syllable should hold the emphasis, and the tone in which it is being spoken, all into the hands of a director. Your play is your baby, and you have to give it away.

And no two directors are the same. I have only ever worked with one director, Christopher Weare, who has over the years become a close friend and the person who most “gets” what I write. When you work with a creative sort, that doesn’t necessarily happen. They’re a funny lot. There may be histrionics. Okay, there will be. They hold very firm creative opinions, and they prize their craft highly, and deserve to do so. And they are exacting; boy are they exacting. That end result that you see from your chair in the auditorium: you have no idea what has gone into that in the preceding three or four weeks.

And when it is solo theatre, it becomes very close, very intimate. As the writer, sitting in on rehearsals, you’re watching a kind of courtship in that space. The director as a spider, the actor as the prey, being coaxed this way and that, until the actor is no longer the actor but another creature entirely. The thing that had been on the page. Which the director has found, and imposed upon the actor.

As the writer in the darkened space, you feel like an intruder, a fly that has no right to be on the wall. Sure, you’re paying them, but that matters not in the creative space.

Here and there, the director will turn to you and ask why you used that word, what did it mean? In rehearsals of my play Cape of Rebels in Cape Town last year, he put his hand up and said, “Yes, but what does it mean? What is it (the play) about? I answered “well it’s about…” and, exasperated, he said, “No no no, we know what the story is, but what is it about?” And then I answered properly, and we got to where we were going.

And it is the getting of that thing that it is about that is the director’s realm, because he has to extract it out of the play which I had extracted out of my head and my heart. And he can’t see in there, so he has to find it in the text. It is a fascinating process to watch and to be a part of.

And now I am in the starting posts of a new piece of solo theatre that is forming and which I will start writing within days, and off we will go again, Chris and me, and together again we will forge this thing and try to make some theatre magic out of my words and his interpretation of them, his bringing to life of these things in my head.

So when I see solo theatre by other practitioners, and when for an hour or more I feel transported into another world, a world that came out of a mind that I do not know, it captivates me and I am in awe, and I understand what they have all gone through to make it work.

Photo: Daniel Mpilo Richards in Pay Back The Curry (Cue/Dani O’Neill)

And that flat, bare stage is capable of holding things so disparate that from one hour, one show to the next, one world has disappeared to make for another which the first would not recognise. Like Amsterdam, which I saw one morning this week, and Blonde Poison, which I saw the next afternoon, on the same stage. The venue was The Hangar, and it’s big, and certainly not intimate. Yet solo theatre breathes intimacy, relies on the audience’s closeness.

.jpg)

Photo: Chanje Kunda in Amsterdam (Cue/Jane Berg)

Amsterdam has travelled to us from Europe and is really poetry made into theatre. Chanje Kunda takes us very personally into her own world, her own life, telling us in well crafted poetry how she decided to leave her dull life in Manchester behind her and move to Amsterdam with her little boy, in search of love, passion and a life that had meaning; how she found it and how it wasn’t necessarily a bowl of cherries, yet how she certainly would do it again. It is captivating and in places poignant, in other parts very funny.

And here’s Fiona Ramsay, in Blonde Poison, and when she walks on stage I am remembering her in the late ‘70s fresh from drama school, in a series of brilliant productions of Steven Berkoff plays by the Troupe Theatre Company, some of them directed by Richard Grant (before he got the “E”), others by Fred Abrahamse, in a company that included a slew of brilliant young actors.

And decades have disappeared behind us and here is Fiona showing a new generation as if to say, “Watch closely, this is how we do it.”

And what theatre this is, what writing this is – as it happens, written by her sister-in-law, Gail Louw. A play that has been produced all over the world; a play of questions more than answers, and that often makes for the best theatre. A play about a woman in Germany during World War II, a Jew who happens to be blonde so that she looks “the part”, you might say. Of a Nazi, that is. And who is she, what does she carry through her long life. What betrayal is there in her heart, and what regret. And should we care, should we still care one way or another all these decades later. A young reporter from a coastal TV station interviewed me on camera afterwards and asked me just that. Should we be seeing this kind of theatre and allowing ourselves to be depressed?

Photo: Fiona Ramsay in Blonde Poison (CuePix/Megan Moore)

Goddamn right we should. We should depress the hell out of ourselves; our writers and theatre makers should depress the hell out of us. Just look at all the shit going down in our world; we’ve never lived in times closer to the aches and tears of Nazi Europe than the world as it is right now. There is no space in these times for triviality, for rich people trying to get richer and uncaring people trying to care less. These are times when we need to huddle together as if in a bunker, and talk in whispers of ways to get out. Of how to find a path to a future without the Third Reich coming to power, or the Caliphate spreading wider, and wider, and wider, until…

Ramsay. She has not lost a smidge of her massive talent and her mastery of her craft. Far from it, she’s even better than ever. This is a performance, and a production, that you could pick up right now and slap down in the West End or on Broadway and it would hold its own and then some. She may even land a Tony.

She is wry, at times funny, seemingly lost, then assertive and proud. Her character has endless complexity, and Ramsay brings across every possible nuance, every hurt, every fear, and most poignantly every regret; and this is difficult because the character is not easily likeable, and yet, thanks to Ramsay, you do like her. You do feel compassion for her. And in the end, in the denouement, it is thrown back at you in a question. Wouldn’t you? What would you or I have done? And you have to wonder. As to what it is, well, that’s to find out when you see the show.

In another, much smaller theatre, days earlier, I had seen Pay Back the Curry, in which Daniel Mpilo Richards, one of the most exciting young talents in South Africa, performed a series of satirical sketches by playwright Mike van Graan.

‘Curry’ is soooo, soooo funny. And this kid can act. He can do anything. I cried with laughter as he flipped and flopped in and out of a slew of characters and accents; now he’s a white boytjie, now he’s a black dude, now he’s an aunty, now he’s a kugel, now he’s a singer auditioning for Idols (and yes he can sing too). He is ace at physical theatre, and for something like an hour he blasted his way through an avalanche of lines from Van Graan’s wittily acerbic pen with barely a pause for breath. Commit these words to memory: Daniel Mpilo Richards. He will be up there with the greats and it will not take him long to get there.

A word on ovations: I stood and applauded for Richards, as I did days later for Ramsay. But hey, what’s this ovation-at-every-show thing going on in Grahamstown?

I leapt to my feet as Ramsay took her first curtain call, and the audience behind me did too. That is an ovation. You don’t sit there and think, “Mmmmm, I think I might give this one an ovation.” If you’ve thought about it, you haven’t been moved. If you’ve hesitated even for a split second, if you’ve thought about it at all, the moment is lost and the ovation is undeserved. An ovation happens despite you, not because of you. The thrill grabs you out of your seat and yanks you to your feet. Your arms raise and your hands clap like thunder while your feet want to stomp until they ache. That is an ovation. There have been “ovations” at every show – every single show – I have seen in a week. Come ooooooon.

The best ovation I have ever seen was in the early ‘80s one Friday night in the big Monument Theatre in Grahamstown for a famous production of Amadeus with Ralph Lawson and the late Richard Haines. The audience was filled with senior schoolchildren, matrics. As the final line was delivered, the entire audience, 900 people, leapt to their feet as one. The precision, the uniformity, was so perfect you could swear it had been rehearsed. Hitler and Kim Jong-un would have thrilled to the marrow. That is an ovation.

They are not to be squandered, lest they become meaningless. DM

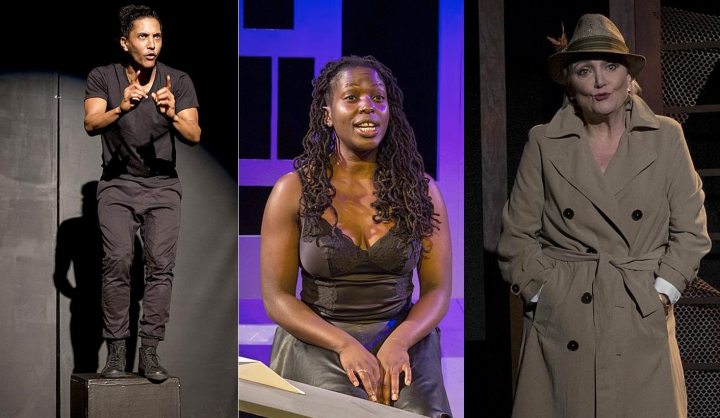

Main photo, (left to right): Daniel Mpilo Richards performs in the fringe comedy show Pay Back The Curry at the National Arts Festival, 3 July 2016. Photo: Cue/Dani O’Neill; Chanje Kunda performs in Amsterdam at The Hanger, July 06, at the 2016 National Arts Festival, Grahamstown, South Africa. Photo: CuePix / Jane Berg; Fiona Ramsay in the solo production of, Blond Poison, on 04 July 2016 in the National arts festival, in the Hanger, Grahamstown, South Africa. (Photo:CuePix/Megan Moore)

Tony Jackman’s solo play An Audience With Miss Hobhouse will be staged at Vryfees in Bloemfontein at the Albert Wessels auditorium from July 11-16. The production, directed by Christopher Weare and starring Lynita Crofford, won a Standard Bank Ovation Award for excellence on the fringe at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown in 2013. Crofford was also nominated for a Fleur du Cap award for her performance. Book at Computicket.

Photo: Lynita Crofford as Emily Hobhouse in An Audience with Miss Hobhouse. Photo by Ross Jansen.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider