South Africa, World

Op-Ed: Reporting Racism in the land of Sunshine Journalism

New Year 2016 saw South Africa waking up to a racist rant from now-household name Penny Sparrow. The next few months would become all the more explosive, down to a church minister labelling black people lazy (and charging R25 for the privilege of listening to the sermon online). Now, post-Brexit, the UK has experienced a wave of racist incidents, ranging from verbal abuse to physical violence and full-blown terror – with Tuesday closing on at least one petrol bombing. Above the chaos, SABC management is singing the same old song: good news stories must reign supreme. Don’t fan the flames. Don’t give the bad guys airtime. Especially if the bad guys are us. But what’s the cost? By MARELISE VAN DER MERWE.

Censorship may not suppress alternative views but rather generate them, and, by doing so, undermine its own aims. – Antoon de Baets

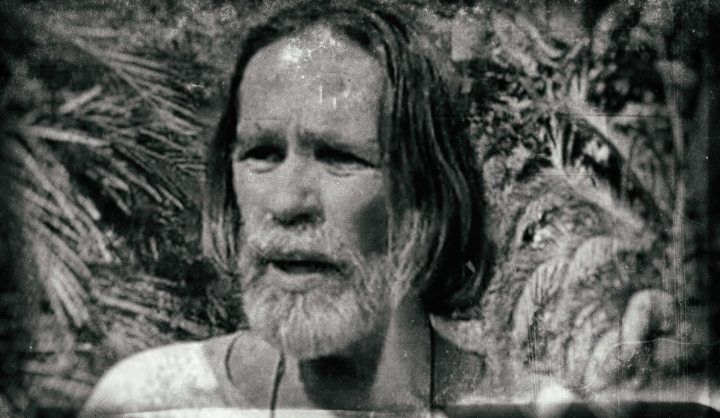

It started with a simple question. We were sitting around having coffee and reading the news. We got to a headline summary of André Slade’s racist outburst. At first we were confused. It was so bizarre it was almost comical. “People having sex in their hotel rooms!” we mused, wondering if the foyer would be more appropriate. “And then they would like them to be cleaned! It’s almost like he’s talking about normal, paying hotel guests… who are neat and tidy?!” Then we started listening to the interview, and the horror dawned on us. There was nothing here to be taken lightly. It was scary, and frenzied, and upsetting.

We felt desperately sorry for the young journalist, Jacinta Ngobese, who had stumbled into the interview. She admitted she was left reeling; while she knew she would be interviewing a racist, she sounded close to tears by the end of the conversation. Surely she was unprepared for what she ultimately encountered. We wondered, in a brief moment of Hlaudi thinking, if it wouldn’t have been better if Slade’s extraordinary rant hadn’t been left buried in his head.

The ambiguity of our reaction, it turns out, is not uncommon. Apparently it’s not helpful either. While it’s tempting to regard severe verbal abuses as the rantings of one rabid racist, or dismiss them as ridiculous, trivialisation is denialism in sheep’s clothing. And numerous studies in South Africa have examined the role of denialism – including by media – in the perpetuation of racism. South Africans may have a great sense of humour, but it’s not always a good idea to use it. Tempting as it may be to shake one’s head, think of an extreme racist as an otherworldly phenomenon or a lost schoolyard bully; minimising the perpetrator is an integral and dangerous part of silencing victims.

So in a year when racist incident after racist incident has been hitting the headlines, how should racism be reported? It’s a key question as the country grapples with a state broadcaster in crisis. Censorship is a more sensitive subject than usual, and South Africa is in no mood to be fed the good news story. So what impact does reporting racist incidents in news and social media have? Does it – in an argument worthy of the SABC – fan the flames? Does it bring to light an issue in dire need of exposure? Or, worst of all, is it one more wave of superficial outrage, a “flavour of the month” in headlines that will go viral a few times and stop as suddenly as it started, making no impact at all?

A preliminary look suggests reportage on racism does have an impact, although the kind of impact is debatable. The recent Gauteng Quality of Life Survey revealed an overall softening of attitudes between races, although on closer inspection attitudes of whites appeared to have hardened while those of blacks appeared to have softened. Researcher Christina Culwick told Daily Maverick that although the survey question itself was open to interpretation, it was possible that grappling with “the nastiness we live with” had had an overall positive effect.

In the UK, an apparent spike in racist incidents post-Brexit has resulted in complaints from “Brexiteers”, not just due to their Leave vote, but in view of alleged mistreatment from media, who they say are giving skewed coverage of the violence. Closer to home, one might ask whether increased reportage of isolated racist incidents can result in greater defensiveness and/or aggression among the privileged, or create an inflated perception of the extent of racism, stirring further anger overall. More positively, reportage can also be validating, allowing victims to feel heard and imparting courage.

Dr Musawenkosi Ndlovu, of UCT’s Centre for Film and Media Studies, describes a double-edged sword. “Some people may conclude that [these incidents] are just the tip of the iceberg… [They] have huge potential to critically impair South Africa’s racial harmony progress if they persist. The damage done to our country by these people is deep. No one knows which racial incident would be the final straw that could lead to catastrophe. Their ‘go viral’ exposure, on the other hand, diminishes the culture of denial about the persistence of racism in South Africa.” The key, he adds, is in the nature of the coverage. “Critical here, especially in a young and hurt country trying to find itself, is the ‘so what’ question. Any good journalist should ask themselves [about their motives].”

News coverage itself leaves little reliable way to assess the extent of racism in South Africa or anywhere else, points out Ndlovu. “The scale of racism is assumed. It is reasonably assumed on the basis of South Africa’s long and immediate history of racism; also on grounds of sporadic, mainly social media-based, incidents of racial insults, and forms of race-based physical attacks in public. Daily, some South Africans encounter racism in private and public spaces. Otherwise, nobody really knows the extent and depth of racism. It could be that racial prejudice is declining or increasing.”

The same may be said of the UK; a simple Google search reveals multiple violent racist attacks in recent months. Looking at the recent rise in reported incidents, it is possible that racists are emboldened by the Leave vote; it is also possible that there is increased attention on racist attacks. It’s also possible that, with increased reportage, victims feel brave enough to report abuse. To use a parallel example, Texas teacher Bridget Kelly was instrumental in changing the policy on reporting rape at The Omaha World Herald (including rape in crime reports, which had been prohibited). After the story of her brutal sexual assault was written by her father, a columnist for the paper, calls to the Texas rape helpline increased by 200%. Victims, feeling represented, started speaking out.

Validation, of course, cuts both ways, and a side-effect is that racist incidents may be amplified and made indelible, says Ndlovu. “The ‘problem’ here, in part, is the change in technology and public communication,” he explains. “A racist’s private conversation, which would have been between two or four people, now occurs in ‘public’, on social media. It gets amplified. It gets recorded and stored. It can be played over and over again. It can be heard or viewed by people across the world. It gets mixed up with other racist incidents in other countries. Legacy media picks up these incidents. They receive comment on social media again, on talk shows and opinion pieces. There is a cycle and loud noise about one subject.”

The cycle continues when politicians chime in and begin to capitalise. Then a new incident occurs in an environment already “crowded with racial noise”. “A sense is created that racism is out of hand,” he says. “People have every right to feel whichever way they want to about racism. The media has every right and responsibility to report racism, the same way it does crime and corruption – also antisocial forms of behaviour. The big problem, for me, is when a serious impression is created that South Africans are nothing but racist. We have many South Africans just getting along.”

But that hardly means one should revert to not reporting such incidents; Kelly’s story illustrates the importance of validation. Unfortunately, denialism isn’t a one-dimensional issue. Just ask Hlaudi Motsoeneng. “

South African media are censoring good news,” he complained earlier this month.

Sadly, Motsoeneng has managed to take a concept that is not entirely fallacious to its most damaging conclusion. The Media Online has pointed out that rationing “negative” news coverage should, logically, also result in a ban on covering racism. (And unfavourable sports results. And corruption. And a host of other problems.) Because, hey, that just brings everybody down.

As Ndlovu points out, news coverage – because it is often crisis-focused – can create skewed impressions; it should be obvious, however, that sunshine formulas are no remedy. The late André Brink famously wrote:

“It is a cliché, but one which cannot be repeated too often: that censorship is not primarily a literary or even a moral institution but part of the apparatus of political power. More specifically, of political power veering towards the totalitarian, and finding itself threatened from within. It is in itself an admission of fear…”

In a country whose leadership fears the confrontation of its own failures, the solution cannot be to remain propped up by a sanitised narrative, one in which it remains the great liberator, the African success story; not the cliché, where it takes the very shape of that which it sought to overcome, the antithesis of liberation.

An early post-apartheid analysis by Associate Professor of Historical Studies at UCT, Professor Sean Field, is instructive. He wrote in The Politics of Disappointment that even the version of reconciliation promised by the TRC was to provide a sanitised version of history to some degree; that “promises of redemption or complete closure are problematic and at best provide some hope and the partial release of emotions through oral testimonies”. At worst, he said, “redemptive claims offer ‘curative’ or ‘spiritual’ solutions which evoke the unrealistic hope of ‘removing… pain’.”

Field predicted the frustration fuelling restlessness in South Africa today – the reality that pain has not been removed, that trauma has not healed, and, perhaps worst of all, that original wounds are being scratched open where there is ongoing perpetration of racism. Field also raises the important point that victims’ pain is often used for political, legal or financial ends, with “pop psychology [being] appropriated by leaders and officials”.

“The legal or political closure desired by lawyers and politicians is not equivalent to the ongoing struggles of trauma survivors to at least reach a symbolic emotional closure. But emotional closure in the complete sense is not possible,” he adds.

Publicly, South Africa is the success story; privately, its struggles are messier.

And so the South African fairy tale begins to unravel. And the increasing need by citizens to tell the story of a country that has not been saved and where racists go unpunished becomes clearer. In this context, the question becomes not, “Does one expose racism?”, but, “How does one reveal racism helpfully?”

If citizens need to speak, it’s the role of media to help them figure out what needs to be said, and say it.

In the case of social media, citizens will do it themselves. A 2015 poll by the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation found that the majority of respondents (61%) felt race relations since 1994 had either stayed the same or deteriorated; nonetheless, 59% also believed the country had made progress on the road to national reconciliation since the end of apartheid, and should keep pursuing this national objective. Call it a mood of resignation, perhaps, to the difficulty of the task at hand; but it appears that in the land of Rip van Winkle, citizens are waking up.

A spate of viral racist incidents might be just this – a demand to be heard, to be released from the 1994 fantasy which no longer serves the country’s citizens. They’ll tell their story on social media and they’ll tell it at the voting stations. Meanwhile, the public broadcaster may be singing a lullaby, but nobody else is sleeping. DM

Original photo of André Slade by EWN’s Clement Manyathela.

Read more:

Become an Insider

Become an Insider