Maverick Life, Sport, World

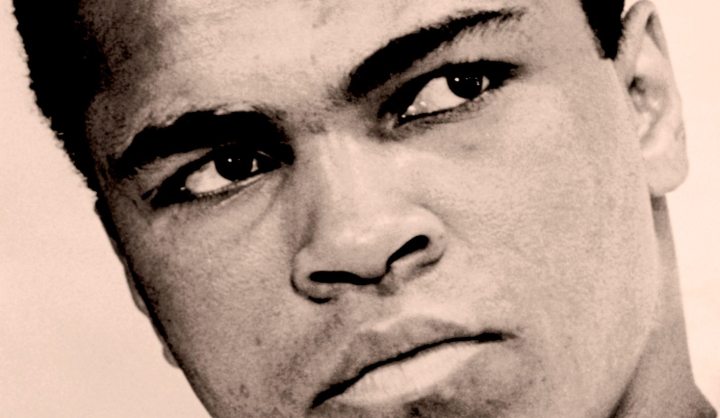

The Greatest: A Tribute to a Prometheus of the Boxing Ring

In thinking about Muhammad Ali, J. BROOKS SECTOR inevitably reaches for mythic comparisons to speak about a unique life.

This past week, Muhammad Ali’s funeral procession wound through his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky as thousands drew near to say their final farewells to a hometown hero who had become a national and then, increasingly, global icon. The memorial service brought together family and friends, Buddhist, Muslim, Christian and Jewish clergy, celebrities and pre-teenagers, and even an ex-president in the person of Bill Clinton. Ali had reportedly outlined the entire contents of what he had wanted in this memorial service before he passed away.

All were united in praising the late boxer’s extraordinary skill in the ring, his magnanimity as a person and the light, the encouragement and the comfort he brought to people everywhere both from his skills as a boxer and the content of his character. It is astonishing to recall that Ali’s sports career had already ended some 35 years ago, while his boxing career spanned the two decades before that.

Perhaps the highlight of these tributes came when entertainer Billy Crystal brought his inimitable brand of humour to bear by remembering Ali’s warm embrace of Crystal’s own mimicry of the boxer – as well as Ali’s willingness to drop everything and join in the many fundraisers and other campaigns for international cultural-humanitarian efforts that were reflective of Ali’s own values and beliefs in bringing light, metaphorically, to others. Or, as Crystal had said, “Yet at his heart he was still a kid from Louisville who ran with the gods, walked with the cripple and smiled at the foolishness of it all.” In the telling of such tales, his eulogisers performed a magical act that transformed Ali into a kind of secular Prometheus for our contemporary world.

When this writer was still young, a favourite weekend excursion was to visit the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The building was – and remains – a magnificent Greek revival temple perched atop a small hill at the confluence of a particularly scenic bend of the Schuylkill River and one of the city’s main downtown traffic arteries. The museum contains an especially striking, jumbo-sized work by Peter Paul Rubens, depicting the legendary Greek titan, Prometheus, punished with having his liver forever being plucked at by an eagle. Prometheus, of course, was the titan who had stolen wisdom, knowledge, and fire from the gods and given them to humanity.

The steps leading up to the Philadelphia Museum of Art from the street were also the steps where the fictional Rocky Balboa had completed his triumphant runs through Philadelphia in his cinematic training regimen. And so, connections from Prometheus to Rocky to Muhammad Ali are not all that hard to find, really. The film’s creator, Sylvester Stallone, has said the real-life model for Rocky’s ring antagonist, Apollo Creed, was none other than Muhammad Ali (and isn’t Apollo the name of a Greek god as well?). In fact, the actor Carl Weathers, who had portrayed Creed, even looked and sounded uncannily like Ali. Creed’s fictional ascendancy came just as Ali’s own star had begun to fade in the actual boxing ring. After Ali’s death, innumerable people around the globe, in their encomiums on Ali’s life, in an echo of Prometheus’s legendary actions, have pointed to the special light Ali brought to the world by virtue of his actions and his values.

In a way, it seems more than a little astonishing and a special irony that Muhammad Ali should have become such a near-universal hero as a person, rather than just as a sports legend. His great sporting triumphs came in a small enclosure where his assigned task was to try to beat another similarly trained person into unconsciousness by the quick and skilled use of his fists, rather than from any great moral teachings or some miraculous invention.

His self-endowed sobriquet, “The Greatest”, might have been slightly misleading. Nevertheless, the broad fraternity of boxing historians clearly puts Ali in contention for that label, along with (from among all weight classes) such names as Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson, Jack Johnson, Jack Dempsey, Mike Tyson, Julio César Chávez, Rocky Marciano, Henry Armstrong and Willie Pep as among the greatest in the sport.

Muhammad Ali had his great personal struggles with the government and the law, most notably his three-year battle to avoid jail time and military service by virtue of a claim of conscientious objector status during the Vietnam War. But, were his struggles worse than the travails Joe Louis or Jack Johnson had faced in prior years?

Jack Johnson, of course, was the first black heavyweight boxing champion in America, back in the early years of the 20th century. At a time when racial segregation and an automatic assumption of white superiority was the norm throughout the nation, his public presence as a defiant black boxing champion deeply annoyed many whites. And worse was to come when he was charged under the Mann Act for a romance with a white woman. Stemming from his successful title defence against a white boxer, James Jefferies, Johnson’s victory had triggered white-on-black race riots in 25 states and in about 50 cities.

A generation later, Joe Louis, “The Brown Bomber”, the fighter generally acclaimed to be the best boxer in history after the early bare knuckles era, had raised vast sums for the US war effort during World War II through exhibition bouts where all funds paid in were given over to the government to help finance the war effort. Astonishingly, he was pursued for years for unpaid income taxes on those very revenues, once the war was over and his usefulness had ended. Eventually reduced to near penury, Louis was bailed out by Max Schmeling, the German boxer whom he had beaten decisively in 1938, before the outbreak of World War II.

Later, to make ends meet, he took a job as a “greeter” in a casino. It was a stunning humiliation, echoing the fate of so many fictional boxers in films such as Requiem for a Heavyweight or The Harder They Fall, and so many other cinematic boxing stories, all deeply laden with the moral fable that boxers can rise on their raw talent; they can make scads of money, but then they will have it leeched away from them by crooks, promoters, and avaricious women. Eventually, they will either die in poverty and illness, or find one last redemptive moment to regain self-respect, just before their death, as with lead character in The Champ.

But Ali’s trajectory was very different from such stories. A boxing prodigy from Louisville, Kentucky, after he took the advice of a white policeman to learn to box to avenge the theft of a prized bicycle when he was 12, he shot to global fame with a gold medal in the 1960 Rome Olympics, won while he was just 18 years old. (Years later he angrily threw his medal into the Ohio River in frustration over racial segregation in his home town and beyond.) Backed by a sponsoring syndicate from his hometown – even though Louisville was still staunchly segregated, and including men whose preoccupation, ironically, was in the judging of the bloodlines of racehorses – he turned pro and quickly became a boxing force of nature.

By that time, he had chosen a new name, Muhammad Ali, under the influence of his embrace of the Nation of Islam, and had renounced his birth name of Cassius Marcellus Clay. It was a slave name, though he also shared his surname with the slaveholding 19th century politician Henry Clay. Ali’s family story was that Henry Clay was an actual ancestor, and not just somebody with the same name.

This put him firmly in tandem with much of the growing civil rights struggle as well. At the memorial service, his widow had commented on Ali’s preternatural sense of timing, both in the ring and in life, in his choices and with his pugilistic moves.

Having joined the Nation of Islam, he had renounced violence (although certainly not in the ring), and declared himself eligible to be a conscientious objector to military service during the Vietnam War, with that famous public comment, “I got no quarrel with them Vietcong.” (Nor should anyone else have had one, for that matter.) In a country still largely supportive of the anti-communist fight in that Southeast Asian nation, and almost entirely behind the military that was carrying out that action, what may have been Ali’s toughest fight of his boxing career lasted for three years and cost him everything that might have come his way, including very lucrative title defences, product endorsements and sponsorships.

Watch: All Muhammad Ali’s knockouts

His effort to stay out of jail for refusing military service went all the way to the US Supreme Court before he was finally cleared of any conviction. After that decision he could again seek boxing licences to regain a title that had been unceremoniously stripped from him by various state boxing commissions and federations. In retrospect, given the intensive publicity of Ali’s fight against the draft and likely service in Vietnam, the case should have served as a warning bell to the government – and it almost certainly helped light a fuse to growing opposition to that war and to the draft. That sense of timing his widow had spoken of. (Perhaps only Emil Zátopek, the Czech long distance Olympic runner and Czech national hero, had used his sports fame and prowess to so much political purpose – and Zátopek ran the risk of imprisonment or much worse from his criticism of the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.)

But along the way Ali found an increasingly effective ally who helped him break through as a national cultural and political force, in addition to his pugilistic prowess. Television and radio sports announcer Howard Cosell and Muhammad Ali became on-air verbal “sparring partners” in conversations that engaged and excited viewers everywhere. They were an unlikely duo. Cosell was an acerbic, fast-talking New York City lawyer with the vocabulary of a lexicographer’s filing cabinet. His in-your-face style virtually challenged most interviewees to mutter under their breath that they wanted to kill him. And Ali, of course, had a boastful, arrogant way of talking about himself as a man who could not be caught, let alone beaten by anybody else. And there was that new, vibrant mode of “trash talk”, ahead of virtually everyone else in sports.

But Cosell and Ali found their respective soul mates in each other – in their joint appearances, they were more than just two men in an interview. Cosell would rhapsodise in multisyllabic riffs about the epistemology of the sweet science and then Ali would fix Cosell with a terrifying look and bring forth one of his patented lines such as that he would “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. The hands can’t hit what the eyes can’t see”. Or even let loose with a run of rhymed couplets designed to mock and destabilise any opponent in an upcoming bout.

Photo: Muhammad Ali lying on the ground during the 15th round of his bout against Joe Frazier in New York, USA, 08 March 1971. EPA/DPA FILE

More than almost any other sports figure, Ali had learnt (often from his association with Cosell) how to make the fullest possible use of broadcast media to deliver his celebrity, his boxing skills and the tremendous force of his protean personality right through the TV screen. The very naming of some of his greatest fights, the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa or the “Thrilla’ in Manila”, were tributes to Ali’s ability to shape the semiotics of his bouts.

But his linguistic skill also reached back and drew upon an old form of distinctly African-American spoken word – “doing the dozens”. The usual form of such a verbal battle comes when two men go at each other with increasingly imaginative insults, sometimes ending up with a battle of alternating “Your mama is so…” jibes. Ali, ever the jester, especially when he was dealing with a noticeably uncommunicative or mentally or verbally less than razor-sharp opponent at a weigh-in or joint press conference, could even end up doing both sides of the verbal duel, just to unsettle his opponent even further. The nation (and the world) had never seen anything like it, and they grew to love it when Ali went on one of his rounds of verbal pyrotechnics.

Throughout history, sports stars have almost always been tightly focused in their comments about their chosen sport, or given to speaking in awkward monosyllables whenever anything else came up in an interview. About the only time a sports star could have delivered a public political riposte and gotten away with it was when the much-loved baseball star Babe Ruth, a similarly outsized personality, responded to a question about whether the fact that he earned more money than the president was appropriate. Ever the showman, in the midst of the Great Depression when Ruth was at his peak, he could snap back – “I had a better year.” But in contrast to almost everyone else on a gridiron, a baseball diamond, a boxing ring or a racing track, Ali was unstoppable, once he began to speak.

Eventually, like all sports figures, his time as an athlete began to fade. But by that time, his feelings about Vietnam had become the conventional wisdom of history. His association with the Nation of Islam faded away and he became an adherent of a more “conventional” strand of Islam. He mixed with the great and good, he travelled on humanitarian missions, he met political leaders such as Nelson Mandela and they even did a few moments of sparring for the cameras, and he became the emotional core of the success of the 1996 Atlanta Olympics when he was the immensely popular choice to light the Olympic flame (again, giving light like Prometheus?), at the opening of the games before a global television audience reckoned to be around 3-billion souls.

In his later years he struggled increasingly with the Parkinson’s disease that probably was the result of the boxing ring punishment he had received. And by the time the end came for him, he was largely mute and barely able to walk, but his fame was now so universal that his image was emblazoned on millions of T-shirts, posters and – inevitably – in the reproductions of some of those extraordinary photographs from his glory days in the ring, showing off a stunning physique as well as an unstoppable attitude.

And then there were films such as the biopic, Ali, and When We Were Kings, a laudatory documentary of one of his greatest fights, the “Rumble in the Jungle”. At the end of it all, Ali entered that exclusive pantheon of only a select few, those greatest of sports figures whose reputation had only continued to grow, long after he had hung up his boxing gloves and done his last “rope-a-dope” and that famous “Ali Shuffle” in the ring. DM

Main photo: Muhammad Ali in 1967 (World Journal Tribune photo by Ira Rosenberg via Wikimedia Commons)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider