Africa

South Sudan: An inconvenient justice

Ignoring South Sudan’s need for justice is just putting off necessary pain for debatable short-term gain – and, needless to say, the country’s leaders only have their own interests at heart. By LAUREN HUTTON.

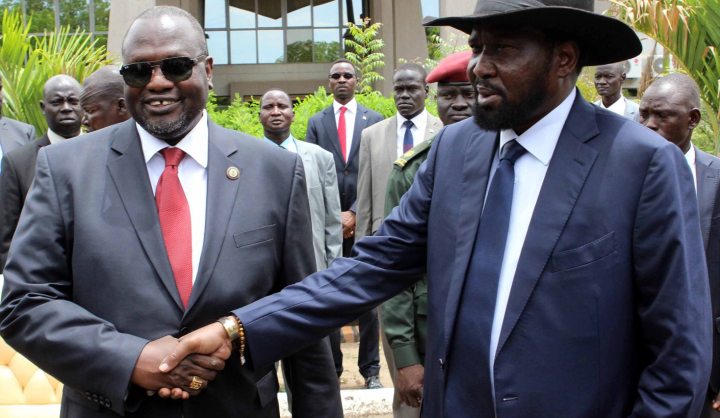

South Sudanese leaders President Salva Kiir and Vice-President Riek Machar have finally found something they agree on: the costs of justice outweigh the need for peace.

While implementation of other parts of the August 2015 peace agreement have just been ignored, delayed or subverted, the leaders went to the effort of writing an op-ed for the New York Times on Tuesday to explain how the victims of the December 2013 civil war do not need disciplinary or retributive justice. Rather, the leaders argued that what’s necessary is a process of “remembering through dialogue, and by so doing affirm the truth of what happened during our bloody civil war” in order to lay the foundations for “building a nation alongside those who committed crimes against them, their families and communities”.

That does not sound too bad. The public relations folks, Ivy League degreed no doubt, who wrote this trough of spin didn’t do a bad job. It’s not the lack of sincerity that stinks the most. It’s not even the completely flawed and unreasonable idea that there is some form of debate between peace and justice or that stability and retributive justice exist on two ends of a spectrum. The reader can even suspend reality and believe that these two leaders just got themselves caught up in a war without reason or direction and now want to work together. What stinks the most to me is that the authors would have us believe that the people with blood on their hands are the lesser evil.

The real issue, however, is what are acceptable levels of violence for a state to exercise against its citizens? And should they be held to account for criminality, war crimes and human rights abuses committed while wearing the colours of the flag? Restrictions of civil liberties are to occur, we are taught to believe, when necessary to combat insecurity. This notion underpins so many assumptions of law and order that it has become sacrosanct.

The South Sudanese state was faced with a threat to its people and territory. Regardless of who shot first, there was an elected government (lacking critical behaviors consistent with law and order but still elected in a somewhat participatory process – it’s all relative after all) and there was a declared rebel insurgency with a stated intent to remove the government by force.

But then the brakes came off – national security needs, narrowly defined, not only collided with civil liberties but shot them into orbit. Counterinsurgency became synonymous with civilian casualties; the war effort was defined not only in territory gained but in assets seized and voices silenced. The reproductive capacity of communities was attacked, their women and girls raped, the young men brutally killed and their assets looted. It was forceful, violent and unjust. It was purposeful. To remove a sense of agency and purpose from violence is to underestimate the worst of human nature.

If the South Sudanese leadership manages to scrap justice for reconciliation, it will be just another step in the cycles of intractable violence that characterise life in South Sudan. It really doesn’t change anything. That’s the point. It’s like an addict: you know something is bad for you, you know it’s wrong but it can always be justified in the moment. The short-term high is better than the long-term damage – just ask any cigarette smoker. Denying justice for the levels of atrocities that have been committed in South Sudan is like buying another pack of cigarettes: it may not kill you today but there’s an increased likelihood of black lung in the future.

The path to future insecurity is laid by impunity, lack of respect for human life, inequalities and greed. Dealing with accountability could offset future human suffering (as quitting smoking would reduce your risk of cancer) but it would also undo the power of the powerful, who will resist it by any means possible (as cigarette companies sought for decades to deny the connection between smoking and cancer and now so astutely find new ways of flavouring cancer sticks). Just two ingredients are required: the will to change and the humility to admit it when you are wrong.

But it is also reductive to equate justice with retribution and punishment. The process of justice serves to adjudicate values in society. For South Sudan, the process of justice is more than just dialogue; it is being able to say what values the society would like to uphold and how. Reconciliation may have worked, to varying degrees, in South Africa, Rwanda and Northern Ireland. But in these cases, reconciliation was only one part of a strategy to untangle and disengage the structures and relationships, which produced violence with ease.

That’s part of the reason why South Africa still struggles to undo the structures of violence associated with economic freedom – we just can’t seem to undo the inequalities that underpin our economy. The point is that reconciliation is part of a strategy to avoid future conflicts; it can only work when the structural factors that enabled the rampant expression of violence are reset. Not only does delaying justice reinforce the use of violence to set power relations, but it denies victims the chance to face their perpetrators and define a suitable justice. It also denies perpetrators of violence the opportunity for redemption.

It is easy for these leaders to write now, in June 2016, that “anything that might divide our nation is against our people’s best interests”. These are exactly the words that should have been said in December 2013 before the very same leaders cut the ties holding the very fragile state together. One part of me is glad that such a realisation exists today but I cannot escape that the levels of violence experienced in the last years are an unconscionably high price to pay. Since the 15th century, Lady Justice has been depicted with a blindfold. In the 21st century, she’s on life support – and the prognosis is not good. And after too many mixed metaphors, all I really want is a cigarette.

Addendum

And after a cigarette break, I now read that Machar is denying that he co-authored the article. And with that we have a return to normal world, where Kiir and Machar do not agree on anything and, for sure, did not author that trough of spin. So why did I get my knickers in a knot? I hate it when I fall into propaganda games – but they make it just juicy enough that years of self-righteous indignation requires public expression. Sigh, I am officially part of the machine. DM

Photo: South Sudan President Salva Kiir (R) shakes hands with former rebel leader and First Vice-President Riek Machar (L) after a new unity government was sworn-in, Juba, South Sudan, 29 April 2016. South Sudan President Salva Kiir named a new unity government sharing power with former rebel leader Riek Machar, ending a conflict that erupted since mid-December 2013. EPA/PHILLIP DHIL

Become an Insider

Become an Insider