Maverick Life

Book review: Bongani Madondo, throwing daggers from the corners

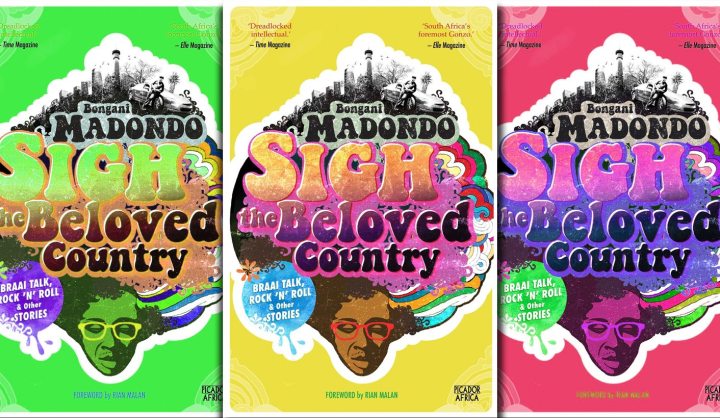

A decade after his debut, Hot Type, Bongani Madondo is back with Sigh, the Beloved Country. Put down what you’re doing, pick up the book, and back carefully into a comfortable chair. Now take a deep breath. You’re going to need it. By MARELISE VAN DER MERWE.

Hot Type, when it was released, was described by Books Live as a “firecracker”. It’s a good description. There is something electric about Madondo’s style. One has the sense of words crackling off the page; a suggestion that something could explode at any minute.

Sigh the Beloved Country has the same energy. Letting Madondo take you on a tour through South Africa is the literary equivalent of taking a road trip with Magritte, with Escher narrating the GPS: surreal, frenetic, and no – do not assume that is a pipe. Yet it seems oddly effortless. Madondo slips easily from one genre to the next: from an essay on race, to memoir, to fantasy; from an analysis on violence to satire; current affairs to letters to an ode to Miriam Makeba.

He humanises headlines and skewers celebrities. One moment the reader is being accosted by a litany of uncomfortable truths and the next they’re laughing out loud. You can’t be sure whether your social/political psyche is getting punctured by the country’s most devastating analyst or whether you’ve just found your new, most wanted dinner guest. (Heck, maybe that’s what makes a great dinner guest.)

Still, the years have left their mark. There’s rage and sadness in Sigh the Beloved Country. It’s funny, but also melancholy. There’s a gravitas that has grown in weight and volume since Hot Type. Madondo, like the country, like all of us, has grown older.

I wanted to ask Madondo, after reading the book, why he writes. It took a while to figure out why this one ostensibly silly question was bothering me. He devotes an entire chapter at the start of the book to skirting around the subject, quoting, among others, Bessie Head, and dabbling with some of the reasons why writing is important.

“Make no mistake,” he writes, “South Africa is exhausting. What we never say enough, though, is that South Africa is also enchanting, complex, beautiful, confident, unsure, insecure, and spirit-roiling. It is both a magical and crippling country. This is what this shit is about.”

It eventually came to me: I was bothered because it’s the one question Madondo doesn’t answer directly, despite the above-mentioned chapter. When you think about it, though, it’s obvious. He writes because he has to. This is what this shit is about. Madondo writes because, aware of it or not, he can’t help himself. The truth must out.

The raw, unflinching and relentless honesty that shines through beneath the technical skill is what ultimately hooks the reader. One can gush, at great length, about the brilliance of Madondo’s style (it is tempting to do so). It is tempting, also, to launch into lengthy analysis of the fascinating and sometimes paradoxical or even contradictory arguments in Madondo’s book. But all this, in the end, is irrelevant. Actually, although Madondo stands at an unusual angle to the universe, often throwing daggers from the corners least expected, his ideas are not always new. That, too, is irrelevant. What makes his book so remarkable is that it is completely skinless; that whether he is examining himself, the reader, a celebrity or anybody else, Madondo’s gaze is unwavering. This book has the unmistakable sting of self-awareness. One lurches because you sense him holding up the mirror without flinching. Sigh the Beloved Country is many things, but it is not performative. Madondo doesn’t write like someone who wants to be a writer; he writes like someone who has something to say.

“Art,” he points out, “is indulgent and elite. And art issuing out of a liberal, however humanist or radical, even more so. People are correctly impatient about artists not aligning with the people, and yet even that impatience is revolutionary bullshit. Which art worth its salt excludes ‘the people’ or ‘humanity’ at its core?”

It is highly unlikely that anyone reading the book will agree with everything in it. In some ways, perhaps, Madondo is the quintessential counter-revolutionary; in others, his writing is his revolution. Some of his notes on race will be pertinent to the Penny Sparrows and Matt Theunissens of the world (spoiler alert: he does not wish to give them undue power) and perhaps also give pause for thought as the country debates the foibles of Judge Mabel Jansen. In what he calls The Black Monster, Madondo gives some perspective on the stereotype of the violent black man:

Growing up in the 1970s as I jived to the electric beats of The Cannibals and The Drive and envied my brothers boogying to David Bowie, I felt a shot of perspiration across the brow every time the shebeen queen in my block blasted the propulsive Soul wretchedness of Bobby Womack, whose voice evoked fear, despair, and red-warning bells all at once. It is also the time I snuck in at the back of the lounge to watch my mother, her friends, and their suitors bump-jiving, cheek-to-cheek to the sounds of Nile Rodgers and his bell-bottom pants Chic. While all of this took place, it felt as though the lilting sounds of pop was just a soundtrack. Something more urgent was at play: the Black vicious monster wielding a panga. Each and every generation has freakzoid names for this male Black Monster. […] Surely, the horror flick starring ‘All Black Males as the Rapist Your Momma Warned You About’ was back at your local barnyard theatre. There have been other templates before, that is, ‘The Yeoville Rapist’, the ‘Denver Serial Killer’, and other scoundrels whose features … matched mine, my friends, relatives, and all male associates’ profiles. We can’t sweet-soak this off: It is true all of those African psychos were Black, but how does that even translate to the notion that all Black men are psyychos out to defile your wife and eat your children’s heart for dinner? […] Despite our best efforts, we could not honestly deny that the face of crime then was the face of the Black Man: that we were it.

Similarly, through the autobiographical story of his family’s love affair with literature, he raises the devastation wrought by forced removals. The tongue-in-cheek title of the essay belies the beauty of the love story contained within; Madondo creates a vivid and evocative world in the story of his family’s multi-generational love of reading. Books & the Madondos’ Status Anxiety is one example of his skill in doing this; in fact, Madondo creates a new universe in every chapter.

When the white man and his grey removal truck moved in, forcing whole African families out, without even considering whatever status and value they might have believed themselves into, he did not quite grasp the extent of heritage, narrative and lineage he done smashed down. Fifteen of the family members, mostly women, were removed from their father’s mansion with its sprawling orchards, Buicks, Chryslers, servants, extended relatives, tenants, and so on, and sardined into a four-room matchbox in the newly built township of Mamelodi East, twenty kilometres out of Pretoria proper.

The content of the book is disparate, but the title conveys the overall tone well: satirical, but delivered with a small sigh of resignation. This is not a light read – as much as the title might suggest otherwise – but it is well worth the investment. And if Madondo is right, there’s no time like the present to do so. Because, in his words: “We all are going to have to do some serious individual and collective soul searching.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider