South Africa

Op-Ed: Language, Knowledge and the Stellenbosch Dilemma

On Tuesday 22 March, Stellenbosch University released a new draft language policy, with a call for comments that will feed into developing the final draft. This article serves both as a submission to this process and a more general reflection on the Stellenbosch taaldebat or language debate, analysed against the backdrop of the language-related conflict that has broken out in recent months on numerous South African campuses. By LLOYD HILL.

Language policy and practice at Stellenbosch University have been the subject of heated disputes for years, but the national student protests that began in 2015 have brought the matter to a head. Consequently, Stellenbosch University finds itself under contrasting pressure to either maintain/implement the current policy – which was adopted in December 2014 and gives English and Afrikaans equal status as undergraduate mediums of instruction – or to replace it with a new policy.

The pressure to maintain and implement the current policy comes in the main from Convocation, the Afrikaans press and various Afrikaans interest groups – notably Afriforum and a new initiative called “Gelyke Kanse” (equal opportunities). Pressure for change comes most notably from the Senate, Student Representative Council, Open Stellenbosch, a new collective known as the “Language Coalition” and a growing number of academic staff members who find the current policy both discriminatory and difficult to implement.

As a response to these countervailing pressures, the new draft policy is equivocal and rather unimaginative. Aspects of continuity and change are combined in an awkward manner that evokes the title of a famous Spaghetti Western, The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. In the following sections, key features of the draft policy are explored thematically as follows:

- The recent history of “language planning” as a policy paradigm at Stellenbosch, other universities and in the wider policy domain (the Ugly);the transmission theory of knowledge that underpins this paradigm, and which sustains inequality (the Bad);

- and the potential to break with this paradigm by means of the devolution of language-related decision-making to faculties and disciplines (the Good).

The draft language policy is to some extent a revised amalgam of the two documents that constitute the current (2014) policy: the Language Policy and the Language Plan. The new draft commits the university to the “advancement of institutional and individual multilingualism” at undergraduate level.

Beyond the recognition of growing language diversity on campus and a vague commitment to promoting multilingualism as a “distinguishing characteristic” of graduates, it is not clear what is meant by “individual multilingualism” or how this is to be promoted. Clearly a tacit preference for English-Afrikaans bilingualism is at stake here.

With respect to institutional multilingualism, the new policy retains the commitment to English and Afrikaans as the principal languages of learning and teaching. The nomenclature and articulation are different, but the essence of the 2014 policy is retained in the form of two (English and Afrikaans) usage configurations: “parallel medium teaching”, which involves the duplication of lectures; and a rather confusing “dual medium teaching” option, in which the paradoxical juggling of continuity and change is most apparent.

A key feature of the “dual medium” option is that “all information is conveyed in English”. But this option can also include “additional support”, notably in the form of “real-time interpreting services from both English to Afrikaans and Afrikaans to English [which] can be offered to students – especially in the initial study years.”

The phrasing of this section therefore appears to address critical responses to the current dual medium specification (the T-option) and the use of simultaneous interpreting. However, in effect it simply repackages the “preferred options” in the 2014 Language Plan. The ambiguous reference to “information” also suggests continuity with respect to key assumptions about the relationship between language and knowledge, which are explored below.

The new draft policy states that the “university places a high premium on the advancement of multilingualism in faculties and support services”. The financial implications of this premium are not specified, beyond a cryptic reference to “incentives for faculties, support services and individuals who excel in this regard”. This and other vague references to the value of multilingualism reflect a certain “language planning” idiom, which tends to foreground “language diversity” at the expense of other dimensions of diversity and inequality, such as race, class and gender.

It is noteworthy therefore that the draft policy contains no references to “race”, (socio-economic) “class”, “gender” or “transformation”. This is consistent with a more general pattern: language advocates and policy-makers in South Africa have tended to treat language planning as essentially a technical exercise – a task for language specialists. Inspiration for this can be found in many contributions to the international literature on language planning – a subfield of applied linguistics.

Language planning as an institutional enterprise is not implicitly “bad”, but it tends to be “ugly”, i.e. it involves conflict over resources in the name of “a language”. Attempts to make it “pretty” or “scientific” tend to mask its roots in 19th century nationalism. In the more recent literature on language planning, the preferred term for scientific language development is “status planning”, but this notion tends to mask the underlying social and political issues at stake. In reality, languages are inextricably embedded in social inequalities defined by race and class. The tendency to ignore these connections is increasingly placing macro-institutional language planning on the back foot.

A number of recent events are precipitating a process of rethinking the social and political costs of using many languages in higher education and in other relatively high status domains of South African society. These include:

- Racialised language-related conflicts on numerous campuses;

- The reformulation of language policies at many universities;

- Continuing legal debate over an Equality Court ruling that it is not necessary for legislation to be translated from English into the other 10 official languages;

- The effective collapse of the Pan South African Language Board (PanSALB), following the Arts and Culture Minister’s decision to dissolve the board in January this year.

The new draft language policy therefore reflects a more general tendency in the local literature on language planning: the abstract valorisation of “multilingualism”. In the draft policy, the promotion of “multilingualism” (in reality, bilingualism) rests on problematic assumptions about the relationship between language and knowledge.

While the prescription of parallel medium instruction and real-time interpreting is presented as a multilingual solution, it is difficult to see how these options can be reconciled with the university’s transformation goals. Notable in this respect is the stated commitment to demographic change, where currently 62% of students and 78% of academic staff are white. For political, economic and pedagogical reasons, the university will be compelled to bring its languages policy into line with both national trends and its own broader vision for the future.

Politically, the university must take seriously Jonathan Jansen’s admission that the main driver of the recent language policy change at the University of the Free State was the tendency for parallel medium instruction to produce predominantly black and white teaching streams. Economically, the costs of parallel medium instruction and interpreting need to be assessed not just in absolute financial terms, but in terms of opportunity cost, i.e. money that would otherwise be spent on bridging programmes, tutoring, training in academic writing and other forms of academic support.

The political and pedagogical costs of real-time interpreting are becoming increasingly apparent at Stellenbosch University. Afrikaans-to-English interpreting is contested by black students, who feel “accommodated” and marginalised by the practice. On the other hand, there is very little demand for English-to-Afrikaans interpreting. The reason for this would seem to be that (predominantly white) Afrikaans speakers are very bilingual and increasingly opt for lectures in English – the language in which they do most of their reading and in which they increasingly need to work after graduating. This trend suggests the core pedagogical problem with the new draft policy: the transmission theory of knowledge that underpins the attempt to maintain the equal status of “Afrikaans for academic, administrative and communication purposes for the benefit of speakers of all the varieties of Afrikaans”.

The phrasing of the new draft language policy – and the language planning discourse on which it is built – manifests what the linguist Roy Harris has called a “segregationalist” philosophy of language. Languages are assumed to be autonomous speech systems – or channels of cognition – which exist independently of writing and other more recent communication technologies.

As discrete forms of speech communication, it is commonly assumed that all languages function – rather like a telephone – as equivalent mediums, capable of transmitting all forms of knowledge (typically understood as “information”). This image of language underpins much of the discourse on multilingualism in South Africa and the problem with this, as Sinfree Makoni and Alastair Pennycook have noted, is that it produces “a way of thinking in which languages are independent of their speakers and may lead to situations in which rights are attributed to languages rather than to speakers”.

And this image conjures up the beguiling idea that universities can and should foster “a realisation of the value of multilingualism and the cognitive nature of the living communication that we experience as ‘language’…” Et voila, Ferdinand de Saussure’s faites de langue become Breyten Breytenbach’s feite soos ’n koei (in die bos). In other words, an analogy with living things (in this case a “cow”) underpins an image of “languages” as natural “facts”. If this sleight of hand is believed, then it is no great leap of the imagination to believe that mother-tongue instruction is a “right” in South African higher education and that action intended to protect one language – Afrikaans in the case of Afriforum Youth’s interdict against Stellenbosch University – serves the interests of all “languages” in South Africa.

The draft policy document contains elements of a different style of thinking about the relationship between language and knowledge production – a subdued “good” alternative. One of the “policy principles” contained in section 6 of the document states that “academic language and literacies comprise sets of complex practices which are linked to how disciplines create knowledge. Such literacies are best developed within the contexts of academic disciplines and their fields of study.”

This important insight should be the centrepiece of the policy. It is noteworthy that the draft language policy is set to replace two current documents: the “language policy” and “language plan”. While the new “concept language policy” combines aspects of these early documents, it also devolves responsibility for developing “annual context-specific language implementation plans” to faculties. This laudable new proposal is, however, undermined by the implicit assumption that language policy is essentially concerned with undergraduate teaching. “Research” is conspicuously absent from the list of contexts or domains listed under “Policy provisions” (Section 7). The overall emphasis therefore falls more on speaking and listening at undergraduate level, and less on reading and writing as a bridge to research and postgraduate study.

Given that Stellenbosch University is the oldest of the historically Afrikaans universities, the instinct to protect and preserve Afrikaans is understandable. But set against the wider context of a higher education system in crisis and a complex new constellation of identity politics on South African campuses, the instinct to institutionalise “languages” as the primary means of managing diversity is misguided.

There are conversations to be had on the status of Afrikaans and other languages within university spaces, but the broader policy conversation needs to reflect the complexity of deliberations at faculty and discipline level.

The “Stellenbosch dilemma” can therefore be summarised as follows: can the identity demands associated with “a language” be reconciled with the discipline-specific learning needs of an increasing polyglot student population? Significantly, the national Language Policy for Higher Education (2002) also advocates “parallel and dual language medium options” as a means of sustaining Afrikaans as an academic medium.

The Stellenbosch dilemma is therefore clearly also a national dilemma. DM

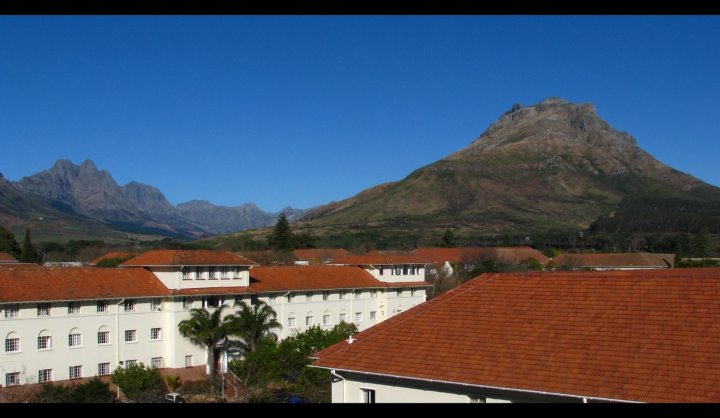

Photo of Stellenbosch University by Chronon6.97.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider