South Africa, World

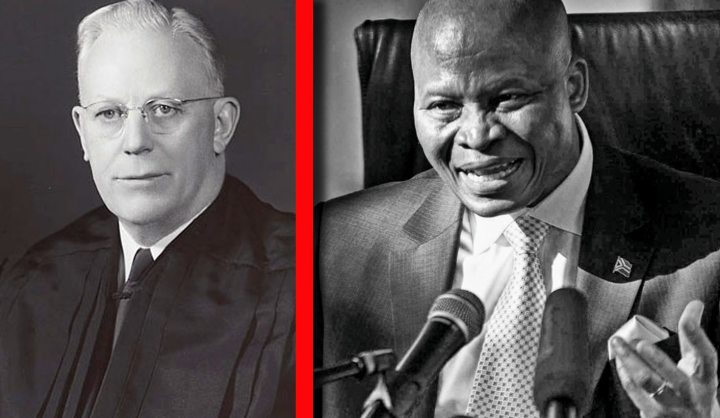

When Judges make history: Earl Warren and Mogoeng Mogoeng

In thinking about the actions of Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng, J. BROOKS SPECTOR reflects on the importance of what a chief justice and a top court can do when it does what must be done.

In the past few days, there has been a flood of sudden, positive commentary over the way Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng stepped up to the plate and obliterated a reputation of being the near-empty vessel tool for the president. Instead, for many, perhaps most South Africans, he has unexpectedly morphed into the local equivalent of Henry de Bracton, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Moses the Lawgiver – in one tidy, compact package.

Justice Mogoeng’s moment of triumph and redemption came on Thursday as he read out the unanimous Constitutional Court decision in the matter of the large amounts of public funding that had been illegally spent on the president’s Nkandla homestead, the need for Number One to repay these monies, and for both president and Parliament to take an exceedingly sharp, very public rap across the knuckles for traducing the country’s Constitution.

Instead of being derided for his sins, Justice Mogoeng has become a national paragon of jurisprudence (except, perhaps, for those people who think he may still have something to account for over a number of judgments related to rape). Justice Mogoeng’s astonishing apotheosis into national hero – with chances for yet more approbation as various other similarly important, controversial cases make their way through the country’s judicial system – has triggered a memory of the same journey US Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren travelled in America about 60 years ago (unless you were an arch segregationist or police thug).

Earl Warren had been California’s attorney-general and then that state’s governor during World War II. In that period, he had vociferously supported the rounding up of all Japanese nationals resident in California, as well as US citizens of Japanese descent, on the grounds they were an obvious fifth column of potential spies, enemy agents and saboteurs. Warren had written at the time, “The Japanese situation as it exists in this state today may well be the Achilles heel of the entire civilian defence effort.” While this endeared him to other Republicans (and not a few Democrats), it had earned him no gold stars from defenders of civil rights and constitutional values – or from the victims of that round-up.

Then, in 1952, in the midst of growing national panic over the seemingly unending war in Korea and the fears of a communist spy epidemic as claimed by Senator Joe McCarthy, Warren was aiming for the Republican presidential nomination as the “favourite son” candidate of California delegates at the GOP national convention. He was eventually beaten to the nomination by Dwight Eisenhower, who had gained Warren’s support with a secret understanding he would nominate Warren to the next vacancy on the Supreme Court.

Then, when Chief Justice Fred Vinson suddenly passed away in 1953, Warren was appointed, first as a recess appointment, and then confirmed by the Senate as his replacement, with Eisenhower noting privately that Warren “represents the kind of political, economic, and social thinking that I believe we need on the Supreme Court…. He has a national name for integrity, uprightness, and courage that, again, I believe we need on the court”.

According to many historians, after watching Earl Warren’s Supreme Court in action for a few years, Eisenhower, as a largely conservative politician, is reported to have said to his brother that Warren’s appointment had been “the biggest damn fool mistake I ever made”. Todd Purdum, writing in The New York Times, went on to add that as Chief Justice, Warren had “discomfited him [Eisenhower] with the Brown v. Board of Education ruling ordering desegregation of public schools, and other liberal opinions.”

More recently, of course, a George W Bush appointee, John G Roberts, had been the deciding vote as chief justice in favour of the constitutionality of the Obama administration’s signature legislation, the Affordable Care Act, to the horror and dismay of Republicans across the nation, so one never really knows how a justice will go, once he or she is freed from more quotidian political concerns.

Meanwhile, returning to the Warren Court, constitutional scholar Melvin Urofsky argued that while Warren’s own jurisprudence was not as carefully drawn up as such giants as Louis Brandeis, Hugo Black or William Brennan, nevertheless, Warren’s strengths were in his public gravitas, his leadership skills among the other justices, and in his firm belief the Constitution guaranteed natural rights – and, crucially, that the court had a unique role in protecting and defining those rights. Meanwhile, political conservatives howled their dismay over the decisions made by the court he led for over a decade and a half. The Warren Court legacy includes monumental decisions such as Brown v Board of Education, Baker v Carr, Reynolds v Sims, Gideon v Wainwright, and Griswold v Connecticut.

The 1954 decision, Brown v Board of Education (bringing together a number of similar cases), coming at the beginning of Warren’s tenure, eliminated the legal basis for segregation in American schools under the “equal protection” clause of the Constitution. This decision helped give great impetus to the broader civil rights revolution that was beginning to gather force in the country. This decision was a dramatic, radical shift in the Court’s focus away from property rights protection and towards a strengthening of civil rights as part of the national discourse and legal framework.

Compounding this revolution, Baker v Carr and Reynolds v Sims in 1962 and ‘64 overturned the previously legislatively approved, gross malapportionment of state legislative chambers that was almost inevitably to the extreme detriment of those in urban areas. In Reynolds, Warren himself had written for the court, “To the extent that a citizen’s right to vote is debased, he is that much less a citizen. The weight of a citizen’s vote cannot be made to depend on where he lives. This is the clear and strong command of our Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause.”

Anyone who has ever watched an American police drama on television or in the cinema is very familiar with that spiel the police tell anyone being arrested about that presumed malefactor’s constitutional rights. In three separate but related cases, Gideon v Wainwright, Powell v Alabama, and Miranda v Arizona, these now-familiar rights of the accused became the universal law of the land – in what is often called an accused criminal’s “Miranda warning”. The Warren Court was also busy with extending First Amendment (free speech, freedom of religion, freedom of the press) rights, as with Engel v Vitale, the decision that outlawed mandatory school prayers, and with Griswold v Connecticut, where the Warren Court set out the constitutionally protected right of privacy for citizens.

Probably none of these Warren Court decisions would have found favour with President Eisenhower in advance of Warren’s appointment – let alone with most of the Republican senators who voted to confirm his appointment to the court. But Warren’s leadership, along with the other justices he shepherded towards these and other decisions, staked out a new national legal territory on behalf of a civil rights culture.

PBS (the US Public Broadcast Service), in summing up Warren’s life, said, “Although he came with no judicial experience, no sign of literary talent, and limited familiarity with constitutional issues, he enjoyed power and was astute and decisive in its exercise, and he was determined to set his stamp upon the Court…. Within a year Warren had managed to bring a divided court together in a unanimous decision, Brown v Board of Education (1954), overturning the infamous 1896 ‘separate but equal’ ruling in Plessy v Ferguson with regards to public education. The new ruling banned segregated schools and gave birth to the modern civil rights movement. Throughout the South, billboards proclaimed ‘Impeach Earl Warren’. Tough-minded, amiable and persuasive, Warren led the court to landmark decisions throughout the 1960s that extended individual rights and the rights of the accused and forced the government to justify any attempts to infringe such rights. The Court introduced the concept of one man, one vote, limited the scope of police searches, extended the right of accused felons to have counsel even if they were unable to pay, and recognised a fundamental right of privacy.”

And 20 years ago, Judith Leonard, speaking of her film history of the court, said her documentary aimed to explore the mind and heart of “one of the most revered and reviled men of the 20th century.” Legal Affairs Editor of Newsweek, David Kaplan, reviewing Leonard’s cinematic portrait, had written, “Unlike other Chief Justices, Earl Warren brought to the Supreme Court no reputation as a scholar or judge, nor did he wrestle with the great philosophical issues that fascinated such gifted brethren as Hugo Black or Felix Frankfurter. Instead, Warren brought political prowess – of the kind displayed, for example, in pushing the Court in Brown v. Board of Education to rule unanimously. For him, the goal wasn’t to articulate neutral principles but to reach correct results.”

The crucial point, and the one relevant to our current fraught circumstances here in South Africa, is that virtually none of that Warren Court revolution had been expected when he was appointed, in place of the conservative, rock-no-boats philosophy that was anticipated. This was especially true given Warren’s role in incarcerating thousands of Japanese-American citizens, rounded up and sent to cope in desolate camps in isolated areas in the High Plains and Rocky Mountain states.

Still, Warren himself, towards the end of his own life, had written he had “since deeply regretted the removal order and my own testimony advocating it, because it was not in keeping with our American concept of freedom and the rights of citizens…. Whenever I thought of the innocent little children who were torn from home, school friends, and congenial surroundings, I was conscience-stricken…. [I]t was wrong to react so impulsively, without positive evidence of disloyalty.”

Given a certain other justice’s – and his court’s – probably very controversial, crucial workload coming right at them in the near future in protecting the public, telling some hard truths to power, and calling officials to account when they violate the public trust, perhaps we should pray that the ghost of Earl Warren and other courageous jurists from history will guide them, protect them, and strengthen them in their necessary work. DM

Photo: Earl Warren (Wikimedia Commons); Mogoeng Mogoeng (Greg Nicolson)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider