Maverick Life, South Africa

Op-Ed: Government’s nuclear plans – will it be the Arms Deal 2.0?

The decision to begin the process for the procurement of nuclear plants was published in mid-December 2015 in the Government Gazette, but oddly signed by the previous Minister of Energy, Minister Ben Martins. We are of the view that this is a significant development, although the nuclear programme is not a done deal just yet. Public concern is still warranted as the nuclear deal remains shrouded in secrecy and is following worrying patterns all too familiar when one considers the history of the arms deal. By SALIEM FAKIR and GARY PIENAAR.

Fundamental questions about governments proposed nuclear plans remain unanswered How much more installed generation capacity do we need? That question, in turn, can be answered only by answering a prior question: Ehat is the current and foreseeable demand for additional electricity generation capacity?

In terms of the law (s.6 of the National Energy Act, 2008 and s.34 of the Electricity Regulation Act, 2006) these questions must be answered by regularly revising the Integrated Energy Plan (IEP) and the Integrated Resources Plan (IRP). The IRP is an evidence-based determination of SA’s electricity needs (i.e. the economy’s ‘demand’ for electricity). The prerequisite of an updated IRP is an important legislated check on any unnecessary and wasteful expenditure on large-scale public procurement. It is significant that the process of updating the IRP entails an inclusive and participatory assessment of our energy needs and the availability of the most appropriate resources to meet those needs. Review of the plan must be done in consultation with the National Energy Regulator (NERSA) and must include public consultations.

The process of updating the IEP and the IRP (2010) was begun in 2012, but it remains inexplicably incomplete. Comments on the Department of Energy’s initial draft included pointed criticism of its reliance on out-dated demand data, inaccurate price information, and unsubstantiated assumptions. The draft revised plan, reflecting the realities of the country’s worsening economic situation, suggests that more nuclear power is not needed and that the decision to build additional base-load capacity on the scale entailed by one or more nuclear power stations should be delayed.

In order to avoid expensive infrastructure that will require a vast capital outlay and significant ongoing operating costs for largely spare capacity, the National Development Plan’s (NDP) preference is for the “least regret” option. It envisages smaller-scale gas or renewable energy modular installations that are cheaper, quicker to build, and are more readily adjustable to unpredictable economic growth and associated electricity demand growth. It is for good reason that the ANC’s own recent National General Congress (NGC) also asked for caution.

There are several reasons for exercising caution. First, increased electricity prices over the past few years have depressed demand to a degree not anticipated in the IRP 2010. Depressed demand is likely to continue for a long time to come. Second, a slow-down in our economy has also been influenced by uneven global growth and associated ‘long-tail’ commodity slumps. Third, South Africa’s economy is increasingly being dominated by services. Over the last twenty years we have seen a major structural change in the nature of our economy. Fourth, the growth in distributed generation solutions with massive costs reductions in solar PV and more likely with storage technologies in the future, poses a major risk for long-term base-load options and could threaten electricity utility business models. These trends will also disrupt conventional modes of capital expenditure on large-scale infrastructure projects. Even new generation nuclear technology designs are becoming modular.

Fifth, long lead times and a trend of substantial cost overruns and construction delays (such labour disputes as seen during Medupi’s lengthy construction phase), as well as far higher lifecycle costs of nuclear power (including decades-long decommissioning and centuries of waste management), further increase the risk profile of nuclear power and reduce its attractiveness, especially the full projected 9.6 GW.

Real costs must take into account financing costs and other hidden costs related to regulatory compliance, insurance against disasters, and loan guarantees that the state has to provide because private finance is risk-averse and hence unaffordable. Capital and debt repayment costs, and currency hedging due to exchange rate volatility, are particularly significant factors associated with foreign purchases, especially if there are construction delays, but financial planning precision is notoriously elusive and indeterminate. Hidden or variable costs include future costs like the importation of skilled staff and equipment, the price of uranium, inflation, exchange rate fluctuations, and plant refurbishment costs over the 40-60 years’ plant operating lifespan.

Six, the “learning rates” (cost reductions due to technological innovations) for nuclear have tended to be negative for generation three-plus designs rather than positive, given that most nuclear reactor designs are “re-versioned” designs of older forms of reactors like the EPR, APR 1000, etc. New designs have proven to be 3 to 4 times more expensive.

All of these factors suggest that nuclear generation capacity is prone to two possible extreme price pathways in terms of construction costs and electricity pricing. If all things go well, it could be a competitive source of energy. However, if problems arise, prices could be the highest of all types of generating technologies.

Are we at risk of the nuclear deal repeating the mistakes of the arms deal?

Government’s apparent haste and disregard of lawful processes and procedures appear uncannily like those that gave us the economically and politically damaging arms deal. First, Cabinet is again driving and managing the process. This ensures that decisions will be secret, as records of its proceedings are excluded from the ambit of the Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA). The collective responsibility of Cabinet members also makes it more difficult to hold individual government representatives to account. Cabinet was a primary location for risk associated with the arms deal, which represented the victory of politics over the public interest, of conflicts of interest and cronyism over accountability. Cabinet took decisions that ignored expert advice that was kept secret from citizens. Arms deal procurement criteria and determination of “needs” were changed by Cabinet members midway during the arms procurement process, with no independent oversight. Efforts by SCOPA to exercise ex-post parliamentary oversight were notoriously muscled aside by the Presidency (see Andrew Feinstein, After the Party, Verso, 2010).

In the case of nuclear plans, a Cabinet sub-committee – the National Nuclear Energy Executive Coordinating Committee (NNEECC), chaired by then Deputy President Kgalema Motlanthe, has been replaced by the Energy Security Cabinet Sub-committee (ESCS), chaired by President Jacob Zuma, and including Energy Minister, Joemat-Pettersen.

Worryingly, secrecy appears to operate also between this sub-committee and other members of Cabinet – they were reportedly unaware of the contents of the agreements signed by Joemat-Pettersen until sometime after Russia’s Rosatom broke the news in late 2014. The ability to gain access to key documents and cost studies by Treasury remains uncertain, as these have been classified as TOP SECRET under what government continues to incorrectly term the Minimum Information Security Standard “Act” – it’s merely executive policy.

Second, government seems to lack determination to avoid repeating the critical procurement errors that characterised the arms deal. Thanks to investigative journalists, we now know that, ahead of concluding the arms deal package with its initial R30-billion price tag, the government brushed aside the advice of its own financial experts, as well as their warnings about the serious economic risks involved. The studies prepared for government highlighted the risk of very large foreign procurement exercises.

The first report, on financing the arms deal, was prepared by National Treasury. It warned that paying for the packages could be achieved only by shifting spending from other departments or expanding government borrowing. It noted: “The scope and magnitude of these risks suggest that it is important that government adopt a more, rather than a less, prudent approach to the proposed procurements.” It also correctly predicted that there “is the risk that [the new] operating costs will be greater than expected”.

Treasury recommended one of two options. The first was to permit a slight expansion in the defence budget and allow the department of defence to choose what to buy – “This would entail the department of defence cutting back substantially the strategic packages and ensuring that it enters into negotiations only for packages that it can afford …”. The other proposal was to delay a purchase decision slightly to allow for a “comprehensive review” in which the conflict between defence needs and budgetary imperatives could be properly reconciled.

Instead, Cabinet chose the option that was expressly discouraged: announcing the arms deal’s preferred bidders without first addressing the concerns regarding affordability and actual defence needs.

The Treasury study also pointed out that a “Cabinet decision to approve a list of preferred tenderers and to allow negotiations to begin would, in effect, signal that it is committed to defence expenditures in the region of the aggregate amount of the proposed procurements. Once negotiations have begun, it will become increasingly difficult for government to back out of the negotiation and procurement process without losing credibility with international governments and the industry.”

Preparations for a nuclear deal appear to suggest that Cabinet has not learned this lesson from the arms deal. While pricing, or a pricing methodology, are not mentioned in the intergovernmental “Strategic Partnership Agreement” (SPA) with Russia tabled in Parliament in June last year, a particular technology is specified (VVR reactors) as is the initial number of nuclear units (two) and their location – at either Koeberg, Thyspunt or Bantamsklip.

The agreement, signed by Minister Joemat-Pettersen on 21 September 2014, is far more detailed than the other nuclear cooperation agreements tabled in Parliament at the same time; those with the People’s Republic of China, the French Republic, the Republic of Korea, and with the USA. The Russian agreement also essentially shifts all major risks onto South Africa, with very little risk assumed by Rosatom.

For now, it seems the supposed Russian deal may not mean that the deal with the Russia is signed and sealed as it will also have to be subject to the national procurement process. It would seem that for the purposes of the proposed nuclear procurement, National Treasury as a key potential safeguard, has been removed from the process by the New Electricity Generation Capacity Regulations of 2011. While s.5 of the Regulations recognises the need for feasibility, costing and value-for-money studies before a decision is made to procure new electricity generation capacity, s.2 explicitly declares that this does not apply to a decision-making process concerning nuclear energy. Similarly, while the need for due diligence assurance and oversight by National Treasury in terms of the Public Finance Management Act, 1999 (PFMA) is recognised by s. 9 of the Regulations, s. 2 ensures that this oversight is excluded where nuclear energy is the source of new generation capacity. Instead, Ministerial discretion is prominent in the Regulations. One is left to wonder what purpose is being served by the nuclear and other energy costing studies and assessments recently undertaken by Treasury.

The further crucial question is whether a nuclear build lends itself well to a bidding process that allows a price discovery mechanism to kick in. Since a nuclear build has so many uncertainties, the answer is that it is practically impossible given the complexities of a nuclear build programme. The contrary is true of successive rounds of procurement for installed capacity involving renewables and gas. This is more difficult with nuclear, as each site and plant operates in unique geographical and socio-political settings. This is evident in Turkey where nuclear build projects are being undertaken by two different vendors and involve different technologies. Ultimately, vendor choice determines what the deal looks like and how risks are shared.

Our view is that nuclear is not a necessity, and certainly current trends do not justify a full fleet of 9.6 GW. The need for proper Treasury oversight, and even veto can only be ensured if there is consistent public pressure and requirements for more transparency. DM

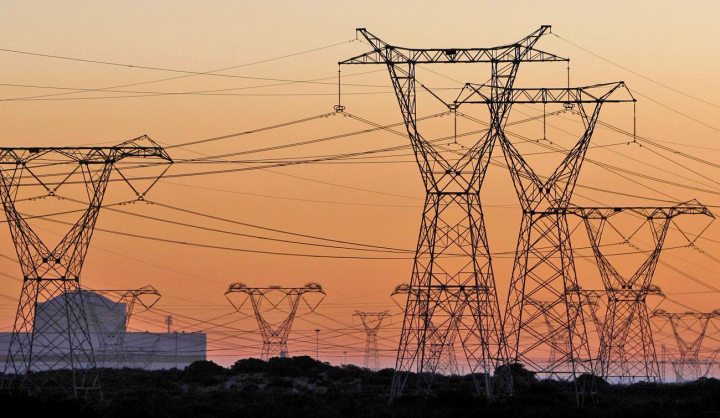

Photo: Electricity pylons carry power from Cape Town’s Koeberg nuclear power plant July 17, 2009. REUTERS/Mike Hutchings

Become an Insider

Become an Insider