South Africa

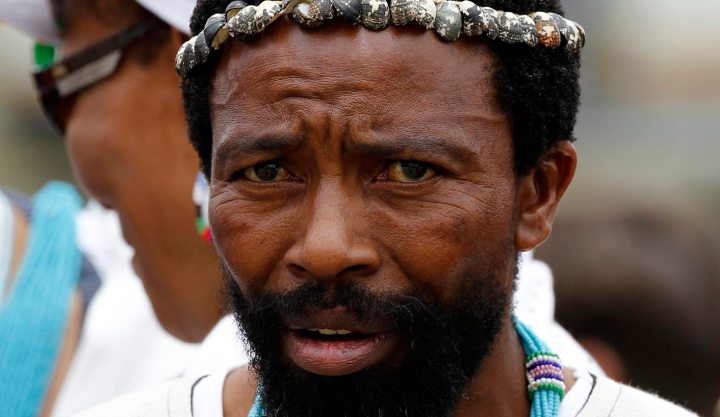

Analysis: King Dalindyebo’s disregard for customary law is the problem, not his conviction

The recent judgment of the SCA confirming the conviction of King Buyelekhaya Dalindyebo and upholding a sentence of 12 years imprisonment has been strongly criticised by supporters of the king. The most vocal critics have been former President of CONTRALESA, Phatekile Holomisa, and Thami kaPlaatjie, advisor to the Minister of Human Settlements, Lindiwe Sisulu. Both Holomisa and kaPlaatjie claim the judgment inappropriately uses ‘western law’ to judge and condemn the king’s actions. Their claim is that this undermines customary law and does not take it seriously as a system of law on an equal footing with ‘western law’. These arguments overlook one very crucial point, which is that it is the conduct of Dalindyebo himself that undermines customary law. By NOLUNDI LUWAYA.

Holomisa and others justify King Dalindyebo’s authority over his subjects on the grounds that he was acting as a judicial officer. Court records show that the king failed to convene a customary court to hear and decide the outcome of the crimes his subjects are alleged to have committed. His failure to do so goes against the well-established practices and traditions of customary courts. These have always been open forums where people can answer to the charges leveled against them, and where decisions about punishment are made by a collective. These courts, which are composed of respected community members, cross examine witnesses, hear the defence of the accused and attempt to mediate disputes so that all can live with the outcome. They are the hallmark of the famed restorative justice approach that characterises customary law.

Western courts, by contrast, centralise authority in presiding officers such as magistrates and judges. They are criticised for their punitive and autocratic approach to dispute resolution, which does not involve community input about how to restore relations of trust and dignity between all parties.

Dalindyebo acted directly against people without giving them a chance to defend themselves in a customary court. This means that he did not, in fact, act in the capacity of a judicial officer. He failed to convene the very forum that would have given him the authority to act in the capacity of a ‘judicial officer’ overseeing a customary court. The king instead ignored and bypassed essential elements of the inclusive restorative justice process that traditional leaders are quick to laud.

In defending King Dalindyebo’s actions by asserting that his role as a judicial officer should offer him protection from prosecution, his supporters are defending western constructs of judicial power. They are entrenching the oversimplification that judicial power resides in the person of the judge, and not in the integrity of the processes that judges oversee. A comparison of the king’s actions to those of a judge delivering sentence after a proper court process is deeply problematic. In the first place it implies that there was nothing wrong with the punishments Dalindyebo meted out. Beyond that it conceals and trivialises the fact that he did not hold a public trial in accordance with customary law processes. This is an attempt to legitimize criminal conduct by dressing it up in the clothes of judicial power. The inevitable implication is the status of ‘judicial officer’ puts all traditional leaders beyond the reach of law, even when they flout the basic principles of customary law.

In fact, what supporters of the King are defending is a distorted conception of traditional leadership that gave leaders unilateral power. This conception was entrenched by apartheid and resoundingly rejected by people living under customary law, both historically and in the present. The recent Traditional Courts Bill that was defeated in Parliament made the same mistake. It sought to centralise judicial power in presiding officers who are senior traditional leaders and to ignore the role of councilors in hearing and deciding disputes. This is one of the reasons that the provinces voted against the Bill. The voting mandate of Limpopo province stated for example that training programs should not be limited to Kings, Queens and senior traditional leaders, but should be extended to all other members of the court. The mandate goes on to state that the bill defied tradition in so far as it envisaged traditional leaders as presiding over the proceedings of customary courts. The Limpopo legislature said instead that tradition does not ascribe such a role to traditional leaders, whose role is to endorse court decisions that are made in council.

It is disappointing that traditional leaders would rally around someone who departed so fundamentally from the deeply humanist principles of customary law. It begs the question: what type of customary law are they endorsing? One that justifies the burning down of people’s houses? Are they defending a customary law system in which a traditional leader is above the law and can act with impunity against his community? Have these leaders abandoned the inherent people-centric conception of customary law captured in saying like Inkosi yinkosi ngabantu (a chief is a chief by the people)?

Accusing the SCA and the ‘western legal system’ of undermining and belittling customary law is, in this instance, a distraction. It distracts us from interrogating the institution of traditional leadership and the worrying trend that traditional leaders can mistreat their communities with no consequences. It distracts us from interrogating recent laws and policies that embolden traditional leaders while stripping communities of their ability to hold their leaders to account. These are issues which require important conversations, conversations that are not aimed at eradicating traditional leadership, but which seek to strengthen the institution by calling on it to put rural people first.

If the king’s actions were to go unpunished this would imply that all traditional leaders, including those who flout customary law in the most blatant way, must inherently be immune from criminal prosecution. The consequences for rural communities would be terrifying. DM

Nolundi Luwaya is Deputy Director of the Land and Accountability Research Centre (previously the Rural Women’s Action Research programme, RWAR) at the University of Cape Town.

Photo: Buyelekhaya Dalindyebo looks on as former South African President Nelson Mandela’s flag-draped coffin arrives at the Mthatha airport in the Eastern Cape province December 14, 2013. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider