Africa

Africa in 2016: The stories we are watching

From contentious elections to concerning economies, 2016 promises to be another turbulent year in Africa. SIMON ALLISON looks at the stories that are likely to dominate the continental headlines.

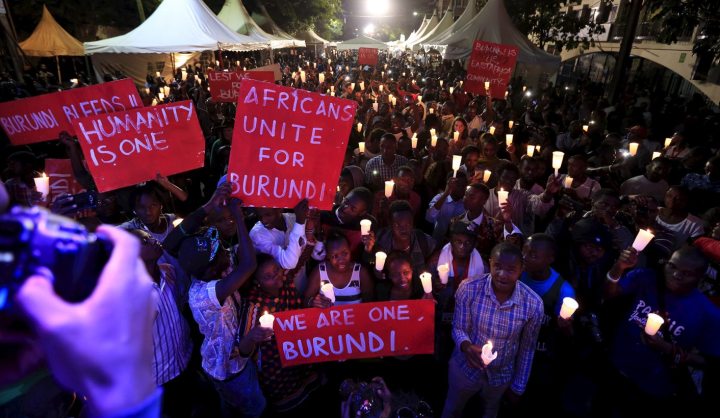

In Burundi, the doom-mongers were right

Prospects for peace in Burundi diminished further this week when the government pulled out of planned peace talks in Tanzania. It has also rejected a proposed African Union peacekeeping mission, leaving the international community little choice other than to sit and watch the situation unfold. At the same time, there are explosions and summary executions in Bujumbura, and rebel movements are reportedly training in neighbouring countries. The number of refugees fleeing the country, often into potentially dangerous conditions, continues to increase. Doom-mongers have been predicting civil war in Burundi ever since President Pierre Nkurunziza announced his intention to run for a third term in office. Tragically, it looks more and more like they may be right.

Kabila’s indecision sparks unrest in the DRC

The third term debate will intensify this year. Several African presidents plan to follow the example of Burundi’s Nkurunziza and hang on to power beyond constitutionally-defined term limits. Paul Kagame has finally acknowledged that he will contest Rwanda’s next elections, while Denis Sassou-Nguesso amended the constitution to allow him to do the same in late 2016.

While none of these are particularly encouraging developments, the one that is most worrying is Joseph Kabila’s poorly-disguised intention to stay in office in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The DRC is much less stable that Rwanda or Congo-Brazzaville, and anti-Kabila protests are gathering momentum – as is the brutal police response to them. Kabila needs to make his intentions clear, and quickly. The best case scenario is that he confirms that he will step down, and concentrates on consolidating his country’s fragile stability through a fair election and peaceful handover. The worst case scenario is that his greed overcomes his common sense, leaving the DRC teetering on the brink of another dark chapter.

Can Buhari deliver change?

Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari got an easy ride last year, with most criticism drowned in the enormous goodwill engendered by his historic election victory against Goodluck Jonathan – the first time in Nigeria that power has changed hands democratically. But he did not get off to a strong start. It took him more than six months to appoint a cabinet, raising uneasy questions about his unsavoury past as a brutal military dictator. He also struggled to make significant headway against Boko Haram (despite his outlandish claims to the contrary). Most seriously, the economy continued to decline, crippled by low oil prices. Buhari’s campaign promised change, loudly. Now it is time to deliver. Does Buhari have what it takes? And how long will it take Nigerians to run out of patience?

Ethiopia’s social contract takes strain

Ethiopian officials rarely dispute the fact that their government is authoritarian. It tightly controls political space, and keeps opposition quiet by means both fair and foul. But this is justified, they say, by the country’s stellar economic growth and impressive development record. Which begs the question: What happens when the economy stops growing?

In December, at least 75 people were killed in student-led demonstrations in the country’s Oromia region. The protests were aimed at halting a controversial plan to expand Addis Ababa into surrounding farmland, with little compensation to current inhabitants. The roots of the unrest go even deeper. The sizeable Oromo population has long been excluded from Ethiopia’s cultural life, and marginalised economically. A stuttering economy and a devastating drought means that Ethiopia’s growth prospects are poor this year. With more tough times ahead, and Ethiopia’s social contract looking ever more fragile, there could well be more civil instability to come.

Museveni not yet ready to tend cattle

Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has a solid plan for his post-presidency. “If I lose the election I shall leave power. I have got my job at home, I am a cattle keeper,” he said last year. It’s hard to imagine, however, that Museveni will adapt easily to life outside State House, his home for the last three decades.

Fortunately for him, he will not have to. Museveni is all but certain to win elections in February, which will keep him in charge until 2021. But a rejuvenated opposition means that to do so he will have to work harder, and break more rules, than usual. There have already been some reports of politically-motivated murders, while a new civilian militia group, known as the Crime Preventers, has harassed and intimidated opposition rallies.

In Kizza Besigye, a veteran opposition figure, and Amama Mbabazi, who defected from the ruling party, Museveni faces two political heavyweights who command very different constituencies. As yet, attempts to form a united opposition have failed. Should they succeed, Museveni may be in real trouble – and his response is unlikely to be pretty.

Peacekeepers must do better

The year has barely started, and already we’ve got our first peacekeeping scandal of 2016, with the United Nations investigating new allegations about its peacekeepers in the Central African Republic. These allegations involve the sexual abuse of four young girls. It’s not the first time that this particular mission has been implicated in exploiting the vulnerable women and girls that it is supposed to protect. Nor is it the only peacekeeping mission to be embroiled in controversy. Elements of the African Union Mission in Somalia, for example, were accused of running a smuggling ring in conjunction with Islamist militant group Al Shabaab. This is simply not good enough. Are peacekeepers part of the problem, or the solution? And what, if anything, will the African Union and the United Nations do to stop the rot?

Dlamini-Zuma’s uncertain future

Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma’s tenure as African Union chairperson expires in mid-2016, and she hasn’t indicated whether she will run again. It’s not an easy decision. For one thing, she knows that her election in 2012 was bitterly divisive, and only succeeded because South Africa used all its diplomatic muscle to bully opposing countries into submission. Will South Africa be prepared to go to battle again on her behalf? For another, she is often mooted as a strong candidate to succeed Jacob Zuma as president of South Africa. A second stint in Addis Ababa will effectively put her out of contention for this, as South Africa’s next elections are scheduled for 2019, a year before her second term would end. Of course, it’s not really her decision to make. As a loyal cadre of South Africa’s ruling party, she will do whatever she’s told, which means the ball is really in President Zuma’s court – and how he plays it will offer a few clues about his future, too. DM

Photo: People light candles during a street concert organized to highlight the situation in Burundi by PAWA254, an activist organization, in Kenya’s capital Nairobi December 20, 2015. REUTERS/Noor Khamis

Become an Insider

Become an Insider