South Africa

Affordable city housing: A model and building Joburg must maintain

When Johannesburg residents avoided eviction and agreed to move from a dilapidated Berea building to City of Johannesburg building in 2007, it was hailed as a victory for engagement and an example of affordable public housing for the urban poor. The model should be expanded, but the City has neglected its building and its residents. By GREG NICOLSON.

Nelson Kethani walks through the courtyard stepping over the sewage. Streaks of green run down the surrounding walls, as though a flood has just subsided. “We always report things but the City doesn’t want to come to the party,” says the well-built 64-year-old. Around him are the four stories of Joubert Park’s old MBV military hospital.

In 2007, after residents of Berea’s dilapidated San Jose building were threatened by the City of Johannesburg with eviction, a court battle led to an agreement that saw them accommodated in low-cost temporary housing. They moved into the “Old Perm” building or MBV, both owned by the City. It was lauded at the time. The residents would not be homeless, and their new rent was tied to their income, set at a maximum of 25% of an occupier’s monthly earnings.

“The MBV and Old Perm properties are tiny oases of public housing in the middle of what is, for the poor, the desert of the inner-city residential property market. They are also a symbol of what the state can do when it stops making excuses and starts delivering,” wrote Moray Hathorn, Lauren Royston and Stuart Wilson at the time. “Ultimately, though, the MBV and Old Perm buildings are monuments to our Constitution, and the socio-economic rights entrenched therein. For without rights to stand on and courts to enforce them, the residents of San Jose and 197 Main Street would have been on the streets years ago.”

While MBV remains a symbol of the right to housing and an important model for inner-city accommodation, residents face continuing challenges as the City fails to maintain the building. When about 290 people moved into what was supposed to be temporary accommodation at MBV, the agreement certified by the Constitutional Court stipulated there would be security against eviction, access to sanitation, access to potable water, access to electricity for heating, lighting and cooking, and that the building would meet accommodation by-laws.

Level by level, Kethani points out the problems. A security guard from a private company, paid by the City, sits in an office at the entrance, but doesn’t look up or ask for my details when we enter. Residents say the security company does not do its job, and the entrance gate is permanently open, leading to crime and unregistered residents moving in. There is electricity and lighting in the rooms, but most of the lights in the hallways and kitchens are out, making it even more dangerous at night.

“There’s no safety. You can be attacked at any time inside because there are a lot of Tom, Dick and Harrys who are here who are not registered,” says Kethani.

In the communal kitchens, many of the stoves do not work and the taps all seem to be leaking or dry. A broken pipe spills sewage into the courtyard and walls throughout the building are water-damaged. Many of the communal showers and toilets are broken, and some of the bathrooms are flooded.

“Same story, the building is dilapidated,” says Kethani, as we reached the fourth floor.

“Fuck” is scrawled on the wall of a communal area residents wanted to turn into a crèche or work space, where they could make the pillows some of them sell on the streets (both ideas were rejected by the City). There’s a mound of rotting food in one of the kitchen sinks that makes me gag. Potato peelings lie in a shower stall in the men’s bathroom. Residents work together to try to clean and maintain the building, but a manager has not been appointed since February, and unregistered residents continue to move in, making it hard to keep order.

This is not the first time we have pointed out problems at MBV. In 2010, Daily Maverick’s Kevin Bloom reported similar conditions. Edward Molopi from the Socio-Economic Rights Institute (SERI), which represents the residents, says there have been repeated attempts to engage the City, and correspondence over the years has continued to ask for issues of maintenance, security, administration, rules and the role of the caretaker to be addressed.

Molopi says MBV is a model of low-cost accommodation that needs to work. Kethani, who is unemployed, pays R160 a month. “Our research indicates that about 50% of households in the inner-city earn below R3,200 per month. This means they can afford to pay less than R800 per month on housing, based on 25% of monthly income. Furthermore, 18 % of households earn between R1,600 and R3,200 per month, and 31 percent earn less than R1,600 per month. This means they can only afford R400 on housing,” he explains. “We are saying that the form of alternative accommodation like the one given in MBV should be permanent and not temporary. Currently I am not aware of any formal accommodation market for these price ranges.

“We just want the City to do what is required of them, and that is to maintain the building and enforce security at the minimum,” Molopi continues. SERI is hoping it can engage the City and is not yet planning to litigate the issue.

Doreen Maduna, 51, moved to MBV from San Jose, and lives with her children and grandchildren. She likes it but there are too many problems, she says. “The building is leaking all over. There is human waste all over. We are trying our best to clean the place, but it’s not enough because pipes are leaking, and the City does not come to the party,” says Maduna as her daughter makes breakfast.

Down the hall, Letticia Ngcongolo, 58, lives in a small room with her three-year-old granddaughter. “Living here is nice, but it is hard,” she says. “The building is leaking everywhere – toilets, kitchens, bathrooms. There are no lights in the kitchen. Everything nje is just disgusting.” Ngcongolo, who has also lived at MBV for eight years, says her granddaughter wants to play in the building, but it is dangerous for children.

While MBV could be a model for affordable accommodation in the inner-city, the City of Johannesburg’s continued neglect of its own property, an oasis of public housing in an unaffordable town, suggests it is only concerned about the urban poor when the courts tell it to be. DM

Read more:

- Joburg’s urban poor: Why the city wishes they didn’t exist in Daily Maverick

- Victory for engagement in relocation from San Jose in Business Day

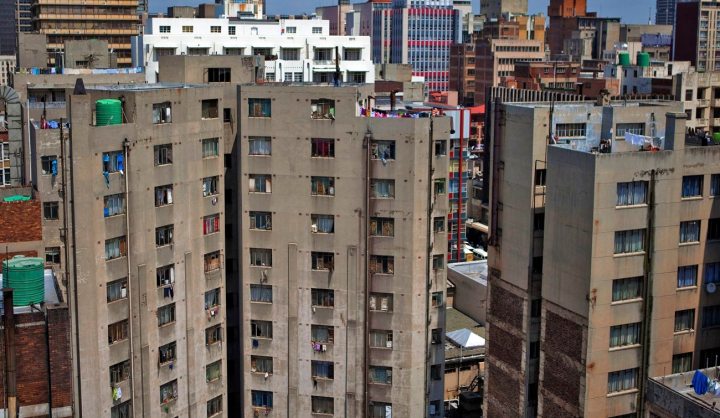

Photo: General view of buildings in the Central Business District of Johannesburg, March 3, 2010. REUTERS/Finbarr O’Reilly.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider