Maverick Life, South Africa

Psyche of the nation: A report from inside the mind of a public-sector child psychologist

Did you know that childhood trauma has a lasting impact on a person’s DNA? Did you know that in South Africa there is exactly one public-sector psychologist and/or psychiatrist for every 300,000 members of the population? KEVIN BLOOM is led from these considerations into a looming national quandary: do we continue to throw our limited funds and energies at ambiguous concepts like Lead SA and the anti-corruption march, or do we move from such externals onto the tougher ground of the country’s roiling inner life?

1. Out of bounds, out of reach

The scene: a pavement café in suburban Johannesburg, the sun in its early summer luminescence, the street a favourite of that caste of South African male whose car and/or motorbike is an unconscious expression of his chronically undeveloped psyche. The question (put to you by the person you have come here to meet): “We can’t use words like ‘damaged’, ‘needy’, ‘abandoned’ or ‘destitute’ because that would compound the psychological problems these children face in later life. At the same time, how do we create awareness – or raise funding – without using these words?”

No doubt, it’s this disconnect between the context and the question that highlights the profundity of both. In the former case, as another man-child on an idling Harley revs his throttle in demonstration of his contempt for all sentient beings, you’re thinking that the interior world of the incurable asshole is almost always on public display. In the latter case, with respect to Dr Shalya Hirschson, the educational psychologist who has just asked you the question, you’re thinking that actual children with treatable psychic wounds tend to live their lives in self-imposed silence.

“Shame,” as Carl Jung once said, “is a soul-eating emotion.” Meaning, if someone (or something) does not intervene, in time there will be no soul left.

And so to restate the Catch-22: how are awareness and funding raised when the mental healthcare of South Africa’s minors implies non-negotiable terms of confidentiality? We are here at this absurd suburban venue because Hirschson cannot, under any circumstances, invite me to sit in on a group therapy session with her patients. The most she can do is tell me stories like the following:

“On the weekend I got a call that an 11-year-old orphan girl at a children’s care centre in downtown Johannesburg was self-harming. I have a relationship with the manageress there, and she didn’t know what to do. There was no qualified practitioner on site; the one social worker for all 50 kids was out. The child was cutting herself and a suicide attempt seemed possible. I made a few calls to get an assessment by a psychiatrist. When she got to casualty at a government hospital, the nurse said she couldn’t see anything untoward – and to bring the child back if something happened.”

It’s a typical example in Hirschson’s experience, and it’s symptomatic of what appears to be an undeclared national pandemic. Not only do we have the manifest failure of the government to implement its own policy guidelines on child and adolescent mental health, we also have the private sector’s obsession, when it comes to corporate social responsibility, with so-called “measurable” objectives.

“It’s all well and good to say we’ve donated 7,000 laptops to high schools, fed 20,000 children, clothed 10,000 primary school pupils,” says Hirschson of the more visible projects to which corporate South Africa donates its time and resources. “That is important, it obviously contributes to childhood development. But if psychological wellbeing is not nourished, nurtured and protected, do we have any chance of raising a generation of well-adjusted individuals?”

2. In comparison with which modern South African literature is mostly meaningless

In 2010, as per this peer-reviewed paper, the total personnel working in public mental healthcare facilities in South Africa was 11.95 per 100,000 of the population. Of those, 0.28 per 100,000 were psychiatrists, 0.45 other medical doctors, 10.08 nurses, 0.32 psychologists, 0.40 social workers, 0.13 occupational therapists, and 0.28 other health or mental health workers. Clearly, these figures, while they do articulate the fact that the mentally ill are hard-pressed to get the attention of anyone but a nurse with a four-year diploma, do not draw a distinction between the mental healthcare needs of adults and children. Neither do they account for the factors that in all likelihood have further eroded the number of public mental healthcare practitioners in South Africa since 2010 – for instance, the impossible administrative hoops that foreign doctors must jump through if they want to practice here.

In the above equation, Hirschson is a rare local phenomenon on a number of counts. She is a psychologist focused exclusively on children; she is a psychologist focused exclusively on the mental health of children who were not born into the blessed community of the medically insured (she doesn’t even buttress her income with a part-time dip into the private practice well); she is a psychologist with a PhD (unlike in the US, Canada and the UK, in South Africa you need only an MA and a short practicum to be deemed official).

Hirschson’s PhD thesis, entitled “Using Creative Expressive Arts in Therapy to Explore the Stories of Grief of Adolescents Orphaned by AIDS,” is testament, in 517 footnoted and cross-referenced pages, to the fact that if anyone has the right to talk publicly about this issue, it’s her. As the thesis states on page IV: “(The) critical ethnographic design was employed in order to give attention to the cultural context of the 16 adolescent participants and how this context influenced their sharing of their grief experiences, following the loss of one or both parents to AIDS.” The thesis goes on to document the data sets that were drawn up from the expressive art therapy sessions, and the reporting of the results is in parts more emotionally instructive (both in content and form) than a lot of the writing that counts as modern South African literature.

For example, this from page 3 of Appendix J: “[Girl X] presented her tree and stated that one of her dreams is to be a mother. It struck me though, that when I asked ‘what are some of the things your mother taught you’ – her response was ‘she taught me to walk’. Had she not internalised or held onto anything else from her mother?”

Or this from the page overleaf: “Towards the end of the session, I was asked if I was going to leave the trees on the wall in the room. I see this as an indication that the group wants me to leave them for a while so that they can reflect on them, think about what we have done in the sessions and perhaps even because they are proud of what they have accomplished. The stories of their difficult lives had been beautifully transformed into a forest of trees that now coloured the dull, cold wall of their chapel room. This showed me that through this session (and previous ones) some of the ugliest and saddest elements of their lives had been acknowledged, shared, witnessed and that the trees were some kind of testimony to the teenagers’ strength and the pride they felt that they had survived many storms.”

In 2009, after returning from a few years in the United Kingdom – where, among other things, she had provided administrative and strategic support to a staff body of 24 mental healthcare practitioners at the department of adolescent psychological services at the Middlesex Hospital – Hirschson formed a not-for-profit that would put her PhD thesis into grassroots South African practice. Called the Uvemvane Project NPC (nonprofit company), its objective is to work with children and families who have experienced trauma, illness, displacement, abandonment, violence and grief. The project also provides psycho-educational services to mental healthcare professionals who work with children. Uvemvane is one of less than a handful of such services in the country.

3. What the DNA remembers, South Africa prefers to forget

But what are we talking about when we talk about the mental health of a nation’s children? If any mainstream publication is trying to grapple with this question from a Western perspective it’s Aeon Magazine, the online long-form journal that is currently making the likes of the New Yorker look about as cutting edge as a gossip columnist at a cosmologists’ party. The Childhood & Adolescence sub-section in the psychology archive includes meditative pieces on (amongst dozens of others): the dangers and dishonesty of adult-to-child esteem-boosting platitudes; the market-driven gender dynamics of the colour pink; the important things that happen to us (and that we forget about) before the age of three; and the long-term implications of the fact that today’s children, who are “cosseted and pressured” in equal measure, don’t have enough time or freedom to play.

A day spent in this richness will be a day that edifies you as to what the world’s most progressive educators and parents are worrying about when it comes to their wards and progeny. Meaning, the archive is elitist – aside from the aforementioned blessed community of the medically insured, there isn’t much here that’s relevant to the continent of Africa.

One piece, however, comes close to compensating for the entire continental oversight. It is entitled ‘Childhood, disrupted’, and it opens with the story of Laura, who at 46 is externally successful, but internally is still reeling from the effects of a bipolar mother and absconded father. The thrust of the piece, backed up by watertight science, is that childhood trauma leaves lifelong scars on our DNA. In the bodies of children whose fight-or-flight hormones are forced to work overtime, the chances of return to a ‘normal’ baseline are slim.

To quote from the science part: “Joan Kaufman, director of the Child and Adolescent Research and Education programme at the Yale School of Medicine, recently analysed DNA in the saliva of happy, healthy children, and of children who had been taken from abusive or neglectful parents. The children who’d experienced chronic childhood stress showed epigenetic changes in almost 3,000 sites on their DNA, and on all 23 chromosomes – altering how appropriately they would be able to respond to and rebound from future stressors.”

The point is that epigenetics, as a local endocrinologist explained to the Daily Maverick a few weeks back, has done away with the concept of genetic determinism. Where we used to think that our genes predefined our hormonal responses to the world, we know now that our attitudes and life choices can have an even greater impact on our genetic make-up. In South Africa, where yet another generation of children is dealing with the psychic damage of domestic abuse, abandonment, illness, violence and grief – to say nothing of the wounds inflicted by poverty and inequality – the odds of reversing a negative DNA imprint are about as favourable as that lone public-sector psychologist and/or psychiatrist to every 300,000 members of the population. So here’s a little question for us to ponder: do we continue to throw our limited funds and energies at low-stakes (because they are hopelessly ambiguous) concepts like Lead SA and the anti-corruption march, or do we move from such externals onto the tougher ground of the nation’s collective inner life?

As the same suburban asshole revs the throttle of the same suburban Harley (dude’s been doing loops), Hirschson waits a moment before continuing. “I was scheduled for a site visit last year to a paediatric oncology unit at a large public hospital,” she says. “On the day of our visit, one of the kids had passed away. My issue was, when the only social worker on the ward was dealing with the kid’s parents, who was dealing with the rest of the kids who had just watched their friend die?” DM

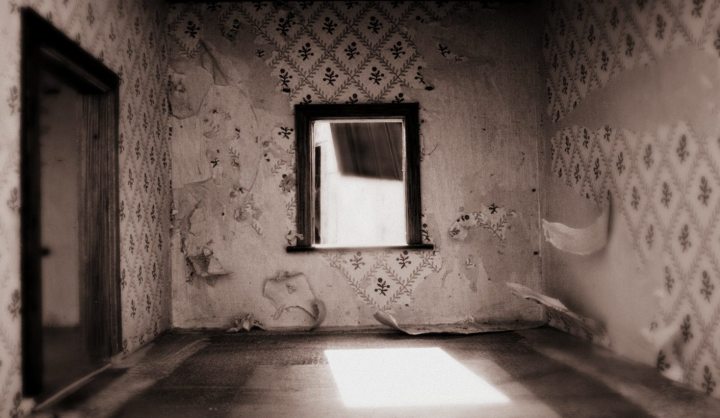

Photo: Dark & Dangerous, by Theresa Williams.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider