Long ago it became one of those South African truisms that opera was some kind of foreign, alien import inimical to the development of the people’s real music. However, in truth, over the past generation, South Africa has come to see (and hear) a real blossoming of world class, classically trained voices.

Many of these singers are talented performers who had their first experience of classical music via school and church-affiliated choirs – the traditional spaces for this exposure, as great operatic choruses have been part of South Africa’s community-based choirs for generations. But in contrast to the harsh realities of the apartheid era, the new generation of singers, increasingly, have also had the chance of thorough training in South African universities, and then opportunities to sing in performances of the great war horses of the operatic repertoire with opera companies in Cape Town and Johannesburg. The best of them have been able to participate in some of the great competitions around the world for rising, young singers. Rather than singers, however, what has largely been missing so far has been an accessible homegrown repertoire on South African themes that audiences can grow to love.

Back in 2010, the Cape Town Opera commissioned five short operas of about 20 minutes each from five different South African composers – Peter Klatzow, Martin Watt, Bongani Ndodana-Breen, Peter Louis van Dijk and Hendrik Hofmeyr – something in the fashion of similarly short commissioned works by the Scottish National Opera in recent years. This is opera stripped down to its basics, one big aria, a duet or a trio, a couple of choruses and then a quick musical wrapping up with each of those works in succession so that the entire collection could be staged and sung over the same evening. Of course, 2010 was a high water mark for South African, self-congratulatory cheerleading, what with a certain football championship on the go across the land, and Cape Town’s opera management clearly thought they could join in the fun as well with a specially commissioned evening of song.

Most recently, the newly formed Gauteng Opera decided to group three of these short works under the name Cula Mzansi, staging them at the Soweto Theatre this past weekend. Gauteng Opera’s determined impresario Marcus Desando had determined that the three works by Klatzow, Watt and Ndodana-Breen respectively would be a production that spoke cogently and forcefully to the questions of memory and remembering – as they drew deeply on South Africa’s history and depicted three telling episodes in the country’s history. History delivered in this manner can have a much greater impact than yet one more dreary, boring, formulaic speech at some national holiday gathering, mumbled by a politician taking a brief break from the trough.

Photo: Words From a Broken String by Peter Klatzow (Amanda Osorio)

Specifically, Klatzow’s work, Words From a Broken String, offered the remarkable story of Lucy Lloyd and //Dabbo. Back in the latter part of the 19th century, Lloyd and Wilhelm Bleek had fastidiously recorded the folk tales, legends, stories, songs and poetry of San prisoners of the Cape Colony – with one prisoner, //Dabbo, a key informant. Lloyd and Bleek were deeply mindful of the fact that the traditional San culture was dying out – and was actually on the raw edge of extinction.

Watt’s piece, by contrast, was drawn from the prison writing of Sestiger poet Breyten Breytenbach, and was titled Tronkvoel (jailbird). This opera, took place in an apartheid era prison and ends with the hanging of another prisoner, even as Breytenbach longs for the time when he can finally be reunited with his Vietnamese wife, living in Paris. The trilogy ends with Ndodane-Breen’s work, Hani, a work that depicts the librettist’s visions and communication with the spirit of South African revolutionary figure Chris Hani, slain by an assassin’s bullet just as the country was moving out from under apartheid’s shadow.

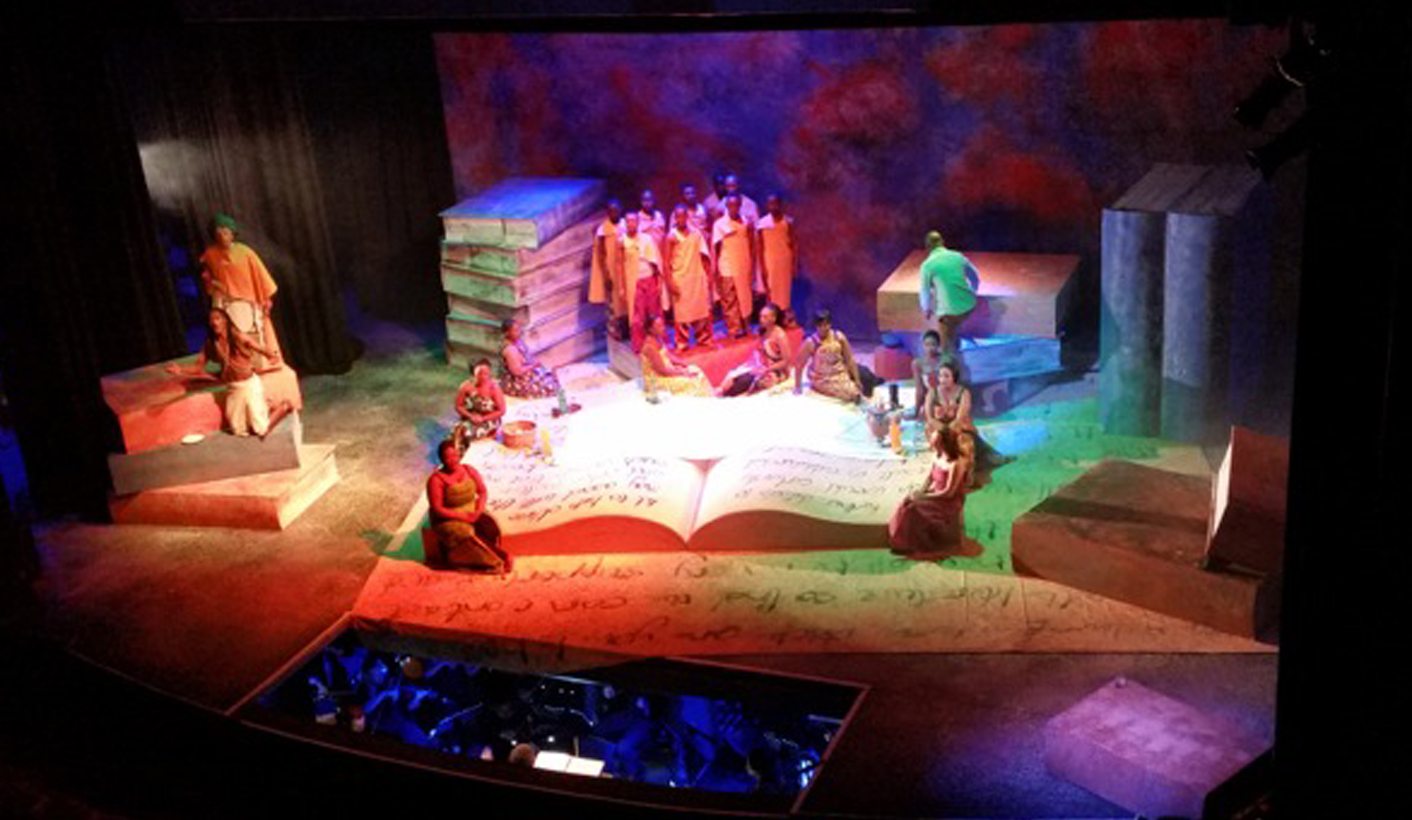

Photo: Ensemble in Hani by Bongani Ndodana-Breen (Amanda Osorio)

In all three of these works, a modern musical vocabulary and idiom predominates, even if these works do not fully embrace all those abstruse, distancing devices like serialism, 12-tone rows and the wilder dissonances of other composers – let alone prepared pianos or other unorthodox instruments and electronically generated sound. Instead, taking compositional cues from composers such as Aaron Copland, Samuel Barber, John Adams, Richard Strauss, and Kurt Weill (and perhaps a light dusting of Carl Orff as well), Klatzow, Watt and Ndodana-Breen’s music remains fully approachable for audience members – even if those audiences could not realistically be expected to depart from the theatre humming any of the arias they had just heard. One partial exception in this was Ndodana-Breen’s use of musical elements from the iconic South African liberation struggle anthem, Senzeni na, as well as the widely known traditional lullaby Thula Baba.

The sets for all three works included large abstract blocks (and a set of jail cells and a hanging noose for Watts’s work). But dominating the stage was an outsized open book – clearly symbolic of the criticality of the word in understanding, preserving and the passing along of the great truths, stories and memories of history. The message from all this should be clear: the failure to embrace history through its words is to lose it. The irony, of course, is that this history was beautifully sung, rather than simply read out to the audience like a tiresome lecture.

Conductor Graham Scott ably led the singers and chamber orchestra for all three works; while Desando directed the first opera, Tshepo Ratona the second, and Warona Seane (the artistic director at the Soweto Theatre) the third. The sets and lighting were designed by the talented Wilhelm Disbergen with a fine eye for delivering eye-catching designs that amplified, rather than competed with the works being sung. And the cast for the three works included fine evocative performances from Phenye Modiane, Khumbuzile Dhlamini, Kagiso Boroko, Coert Grobbelaar, Natalie Dickson, Elizabeth Lombard, Njabulo Mthimkhulu and Thamsanqa Khaba, as well as chorus members and dancers. In particular, the dancers in Klatzow’s work, wearing loincloths and cow horns, evocatively echoed the storyline of loss. Many of these singers have come from musical training with the Tshwane University of Technology or University of Cape Town opera programs as well as time spent with the Cape Town Opera Studio or Johannesburg’s Opera Africa, or other performing groups in Gauteng, before coming to join with the new Gauteng Opera.

Describing her experience as a novice opera director, Seane explained she had never directed an opera before being asked to participate in the Cula Mzansi project by taking on Hani. Describing her cross-disciplinary and cross-cultural approach, she said: “Because of the new territory and the nerves that accompany saying yes to such a challenge, I read a lot around how the opera community see themselves and the form … I listened to the music a lot. A lot. But also the libretto speaks of the Famadihana; a Madagascan tradition of exhuming loved ones, cleaning the remains and reburying (them) and so I searched for sources on the tradition. I loved working on this production very much. I found it excitingly challenging.”

While many critics of this overall joint work, when it was first performed in Cape Town five years earlier, had lauded the event, not everyone had robust praise for it. Composer Michael Blake, for example, had written at the time: “That there is little critique in Five:20 or in most new South African music, suggests that new music in South Africa has not yet created a critical ‘edge’... And this is where a golden opportunity was missed: for where else but in a closed, parochial, self-satisfied university context could one experience the blast of the postmodern new? Where better to make bold new musical statements about our South African-ness? It was expected in every way, not least from the marketing. We were all braced for history in the making: the demand was there, but the supply did not rise nearly enough to meet it.”

But that, surely, is almost besides the point of the composition of works like these. Such works have been designed so that audiences can listen to them attentively and carefully, fully aware of the didactic and moral lessons on offer, rather than simply be available to be awed and mystified by the accomplished, avant garde tricks of the musical trade.

In fact, musical history offers many examples of great operatic composers who have composed works as a pathway for audiences to take on board serious political lessons. As obvious examples, Giuseppe Verdi’s operas such as Rigoletto, were designed to nourish a growing sense of Italian nationalism at a time when much of the peninsula remained under foreign domination – as well as to offer audiences a rollicking, entertaining time while they were in the theatre (Verdi, when asked about his more academic theory of opera, had simply said that the theatre’s seats should be full, after all). Similarly, Beethoven’s Fidelio served as an extended exposition of his belief in the new fervour for political freedoms and human liberties across Europe in the wake of the French Revolution. Even a more modern work like Gian Carlo Menotti’s The Consul delivered a message about the shutting down of freedom and as a signal that political refugees were a major artistic issue for the latter half of the 20th century.

It is a great shame, therefore, that Cula Mzansi only had an abbreviated, three-performance run at the Soweto Theatre. It should have been allowed to build audiences over a longer run – and to have been positioned as a way to attract audience members, either those unfamiliar with opera or those unacquainted with the still new, relatively unknown Soweto Theatre. To cushion the concerns of some people of even being able to find that place, perhaps management needs to look into organising a special express bus departing from and returning to a popular gathering spot like Rosebank or another familiar location. This would mimic the way the Brooklyn Academy of Music helped build its loyal following for its distinct cultural offerings, back when New York City’s audiences often disdained the very idea of travelling from Manhattan to Brooklyn for their cultural edification.

Photo: The prisoners, guards and Breyten Breytenbach in Tronkvoel by Martin Watt (Amanda Osorio)

The audience’s appreciation of the meaning of Cula Mzansi was enhanced through electronically projected surtitles above the stage. Given the fact that, between them, the three works made use of four different languages – English, Afrikaans, Xhosa and French – without surtitles many audience members would have been left out of a deeper understanding of the works as they were performed. Their successful use for this work should encourage other theatre operators to try using surtitles in productions that also make use of South Africa’s diverse linguistic heritage (or even languages largely unfamiliar to the nation’s audiences). Gauteng Opera should also accept that audiences really do want programmes – rather than instructions to look up the details on the internet once they return home. A programme is a sign of respect for the efforts of the performers, every bit as much as a guide to help audiences make sense out of what they are witnessing on the stage – even if it is simply a well-designed, single sheet of black-and-white paper.

Once again, here was a work that deserved a much bigger audience and the embrace of all of those who yearn to understand South Africa’s history. It was a stunningly beautiful way to absorb some of the lessons of the country’s history and probably deserves a national – and even, perhaps, an international tour as well. DM

Main photo: Hani by Bongani Ndodana-Breen (Amanda Osorio)

For more, read:

- Cula Mzansi: 3:20 min South African Operas at the Gauteng Opera;

- History Never Sounded so Good, at the Unisa;

- Martin Watt on Tronkvoel.mov at YouTube;

- Cape Town Opera’s 5 new operas at the ClassicSA.