Maverick Life

Pluto: Because we are human and we long to know

The wonder and awe of the New Horizons space probe’s mission to Pluto inspires J. BROOKS SPECTOR yet again to be amazed by the power of astronomy and imagination.

Way back when this writer was barely a teenager, he built a telescope. Well, okay, he didn’t grind the mirror all by himself (he did get help), but he put the whole thing together out of bits and pieces and got started on some ambitious observational astronomy. There were all those nebulae to see and record, there was the Milky Way galaxy and there was a partial solar eclipse to follow – as well as couple of comets, dozens of double stars, and those magnificent star clusters such as the Pleiades in Taurus.

But for pure excitement there was the Moon and the traditional planets – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Looking at all these objects made one feel at one with those heroic astronomers from the past, like Galileo who was the first to see the mountains and craters on the Moon, the rings of Saturn, the four big moons of Jupiter, a glowing crescent-shaped Venus, and that bright red circle of Mars, all moving through the constellations, just waiting for someone with a telescope.

Becoming an avid reader of the amateur astronomer’s monthly magazine of choice, Sky and Telescope, the writer carefully examined the magazine’s lists of objects to identify when they could be seen at their best advantage – high in the night sky, especially in the winter air. It is just possible that the writer and his friends managed to see Uranus, one of the planets not known to antiquity. The writer joined astronomy clubs to work with larger telescopes and he sat outside until late at night to observe meteor showers – wrapped in an overcoat, blankets and two pairs of gloves. There were dreams of a career as an astronomer – even though that eventually disappeared when it became clear that an understanding of physics required calculus and that, sadly, became a moment of truth.

But the fascination never really ended. As the first images from lunar and Martian landers were beamed back to Earth decades earlier, astronomical exploration continued to enchant. Growing up as the era of space exploration finally became true meant staying up late at night to watch as those first images of the Moon and when those early images of Mars were broadcast on television. The writer realised he was much more interested in the science of these wonderfully complex machines, as they brought science fiction to life, than in dreaming of being one of those astronauts whose missions took them into those repetitive low-altitude orbits around the Earth.

And even as another career happened, the writer continued to marvel at the marvellous imagery from the next generation of planetary missions – and, most especially the Hubble Telescope’s humbling depictions of star nurseries and colliding galaxies at unimaginable distances. But, for this writer at least, it was the two Voyager spacecraft and their movement through our Solar System and beyond – with their encoded messages embossed on a golden plate, designed to explain humanity to any possible inhabitants of other worlds – that seemed almost unimaginably ambitious and audacious.

And now, after nearly a decade of travelling through space, the New Horizons craft has just reached Pluto, right on target and virtually bang-on-time (apparently it was just a touch more than a minute early). The plutonium-powered probe silently roared past Pluto at more than 28,000 mph (45,000 km/h) on a trajectory that brought the fastest spacecraft ever to leave Earth’s orbit to come to within 7,770 miles of Pluto’s surface. Stuffed to the gunnels with cameras and all its other instruments, the New Horizons craft had been designed to gather a cornucopia of images and data as it rolled on by Pluto and its five small moons, Charon, Styx, Nix, Hydra and Kerberos. Forbes Magazine made a point of noting that its power system ran on plutonium, explaining, “This mission was possible only because the radionuclide Pu-238 generates continuous power far out in space where solar energy is too weak, chemical energy is too heavy, and batteries and fuel cells are too short-lived to be of use…”

Stephen Hawking, the renowned Cambridge cosmologist, offered a recorded message of congratulations to the craft’s scientific team, speaking on behalf of all humanity when his message said, “Billions of miles from Earth this little robotic spacecraft will show us that first glimpse of mysterious Pluto, a distant icy world on the edge of our solar system. The revelations of New Horizons may help us to understand better how our solar system was formed. We explore because we are human and we long to know”.

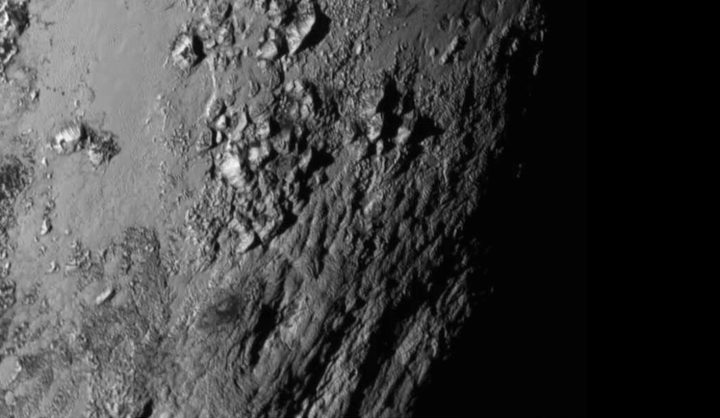

As an engineering, navigational, and scientific feat, the New Horizons’ success has been just about inconceivable to most of us. Think of throwing a small pebble many hundreds of thousands of miles to hit an invisible dot on another fast-moving rock – and that wouldn’t even be close to the difficulty of this project. As it grew closer and closer to Pluto, the pictures New Horizons returned to Earth began to deliver a vision of Pluto (and its satellite, Charon) that became astonishingly detailed. And as is now known, Pluto has gigantic mountains composed out of some kind of ice, vast, rugged landforms – but no craters. That last bit has thoroughly surprised scientists who have been working on this mission. This lack of craters seems to imply – most improbably – that Pluto is a tectonically active orb whose geology somehow erases any meteorite impact craters after they have appeared. This is something virtually no one expected until this week – except for astronomical illustrator Don Dixon. It seems Dixon had painted a picture of Pluto thirty-six years ago that has an uncanny resemblance to the actual Pluto.

Dixon told the media once the real Pluto had been revealed, “I’d like to claim prophetic powers, but the painting was guided by the reasonable assumption that Pluto likely has a periodically active atmosphere that distributes powdery exotic frosts into lowland areas. The reddish colour of the higher features is caused by tholins – hydrocarbons common in the outer solar system. The partial circular arcs would be caused by flooding of craters by slushy exotic ices. Pluto is apparently more orange than I painted it, however; I assumed the exotic ices would push colours more into the whites and grays.” That man deserves a Bell’s!

Until seeing those first images, scientists had believed Pluto should be totally covered with craters, since it is, effectively, part of the inner lip of the Kuiper Belt with all that implies. That belt is a vast ring of tiny planetoids, dust and icy debris that surrounds the edge of the Solar System and it is presumed to be the source of some of the comets that, from time to time, come streaking towards the inner Solar System. Surely some of that stuff should be hitting Pluto all the time, leaving the evidence of those collisions. Or not.

Photo: This new image of an area on Pluto’s largest moon Charon has a captivating feature—a depression with a peak in the middle, shown here in the upper left corner of the inset. Credits: NASA/JHU APL/SwRI

In the weeks, months and hopefully years to come, the data stream from New Horizons’ imaging of Pluto, its measurements of radiation and temperatures, spectrographic analyses, observations in variations in gravity, and other data will slowly stream back to Earth from the probe’s position of around a light year away from Earth. And then there will be those measurements from that unexplored region beyond Pluto that will, soon enough, begin to flow homeward as well. Eventually, if an alien species on one of Alpha Centuri’s planets find this craft, it may come to be like one of those Star Trek episodes where the crew of the Enterprise encounters an ancient, alien spacecraft and try to puzzle out its purpose.

Beyond the new controversies about Pluto and its features, its atmosphere. its core, and pretty much everything else that will be debated for years to come, the nature of Pluto itself has been up for grabs since it was first discovered. But the story of Pluto actually goes back 150 years before that day in 1930 when a young astronomer first found a tiny dot on two photographic plates that jumped when they were compared simultaneously because that distant object had moved in the intervening days between the dates when the two plates were made. Once Newtonian physics – with gravity and all that really important stuff – became understood, it became clear that the orbits of the outer planets of Jupiter and Saturn were not precisely in accordance with the dictates of gravitational attraction as could calculated on the basis of all the known bodies in the Solar System.

To solve that problem, astronomers in the late 18th century became fixed on the idea of finding a new, heretofore unknown planet out beyond Saturn that could put them out of their computational misery. The honour of this discovery fell to William Herschel in 1781, a transplanted German living in England who was a court musician and an amateur astronomer. Herschel applied some serious observational rigour in his night-time hobby and so it was not surprising he found the new celestial body. Initial calculations by more mathematically inclined astronomers soon showed that his discovery of the newly christened new planet, Uranus, accounted for most of the deviations in the predicted orbits of the other outer planets. Almost all of these, but not quite all of them, however.

The remaining deviations continued to drive astronomers howling into the darkness, especially since Uranus’ own orbit now showed some of these same disturbing and perplexing anomalies. Over a half-century after Herschel had found Uranus, in 1846, Johann Gottfried Galle, using calculations by Urbain Le Verrier and John Couch Adams, found a yet further away planet, Neptune. But yet more complex, more exacting calculations indicated Neptune’s orbit was also not quite as predicted. As a result, the hunt began again for a yet-further distant planet, Planet X. Enter the young astronomer, Clyde Tombaugh, who finally found the offending planet on 18 February 1930, making use of those laborious, outrageously tedious photographic plate comparisons.

The new object was named Pluto, for the Roman god of the dark, nether world and when, in the fullness of time, the first moon for Pluto was also discovered, it was christened Charon in honour of the ferry operator who brought the spirits of the dead across the Styx (or Archeron) River and into the underworld.

Pluto, of course, hasn’t quite fit the model of the rest of the Solar System’s planets, not least for the fact that its orbit was significantly inclined away from the plane of the orbits of the rest of the herd – and most importantly, because it actually crossed over Neptune’s orbit every so often, so that for years at a time it is actually closer to the Sun than Neptune is. And eventually astronomers were increasingly convinced it was too small to be graced with the title of being a real planet (although New Horizons seems to have given it back some size and mass). Given the realisation Pluto was closely identified with the Kuiper Belt, it was finally demoted on 24 April 2006 from being a real planet to the indignity of being a mere planetoid.

This undignified demotion has not set well with legions of amateur astronomers, as well as ordinary folks, as Pluto had come to be a kind of mascot planet for many people. There is an argument that blames all this weird affection for a distant frozen chunk of rock on Walt Disney of all people. Within months after the discovery of the new planet, the Disney folks gave the name Pluto to Mickey Mouse’s pet dog, after rejecting the name, Rover, as being too common, too ordinary to use.

It is a great story, and it is true the cartoon dog gained that name just after the planet’s discovery. Unfortunately, no actual record in the Disney studio archives of precisely how that decision came about still exists; so maybe the story is true, but maybe it isn’t. Regardless, dog and planet became a fiercely bonded pair in global affection and people did not take too kindly to their pet planet’s demotion. Now, of course, since Pluto seems to have more to it than before, we are likely to see petitions to restore Pluto to its former standing and glory. And as more and more data about this hunk of rock comes back to scientists, and as they try to unravel the possibility it has a real atmosphere being refreshed by tectonic action from deep within its structure, the more like a planet it may become again.

As a feat of engineering and imagination, New Horizons has now become the latest in a string of fantastic exploration feats in space exploration. But, given the surprises Pluto has already delivered in less than a week, it is likely there will be many more to come as the entire data stream finally reaches Earth and as the pictures and so much more is evaluated and debated by teams of scientists.

Oh, and by the way, amortised over the 10-year period of its mission, New Horizons turns out to have been amazingly cost-effective as a research tool. According to its programme managers, the Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, New Horizons has cost Americans about $.70 per person, per year – much less than a couple of newspapers. Seems pretty cost effective for all the surprises New Horizons has already delivered. DM

Main photo: New close-up images of a region near Pluto’s equator reveal a giant surprise — a range of youthful mountains rising as high as 11,000 feet (3,500 meters) above the surface of the icy body. Credits: NASA/JHU APL/SwRI

For more, read:

-

New Horizons: Nasa’s Mission to Pluto, at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory;

-

Artist’s Decades-Old Painting of Pluto Is Eerily Accurate, at Yahoo;

-

New Horizons: Images reveal ice mountains on Pluto, at the BBC;

-

New Horizons Reveals Ice Mountains on Pluto, at the New York Times;

-

New Horizons Delivers First Close-Up Glimpse of Pluto and Charon, at Scientific American;

-

Pluto photographs thrill Nasa scientists after nine-year mission, at the Guardian;

-

Pluto Tool Kit, at the Nasa;

-

Plutonium Propels Spacecraft To A Close Encounter With Pluto, at Forbes.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider