Maverick Life

Obituary: Omar Sharif – the artist of disappearance

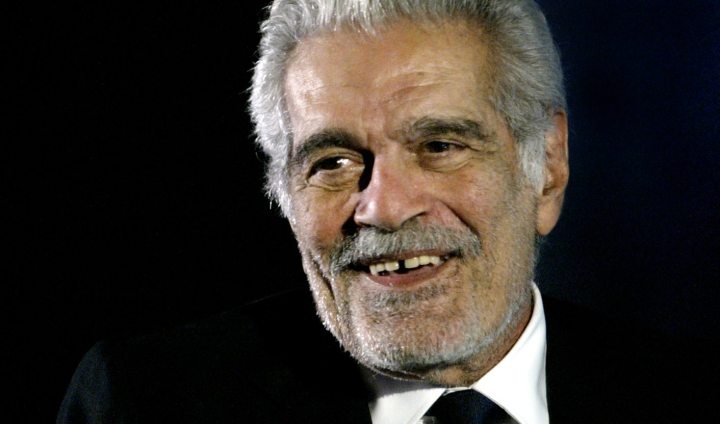

Omar Sharif, who died in Cairo last week, was actually a construct; similarly too the idea of him being a masculine and seductive Muslim Orientalist. He was born Michel Chalhoub in cosmopolitan Alexandria in 1932, the son of Melkite Greek Catholic family of Lebanese descent. By KALIM RAJAB.

When the celebrated expressionist director David Lean was scouting for an actor who could play the enigmatic, soulful character of Ali for his desert epic Lawrence of Arabia in the early 1960s, his Hollywood funders were keen to force his hand and cast a bankable American or European star in the role.

On the choice of the headline act of Lawrence himself, Lean had already had his way in the selection of a young tyro Irishman whom he alone seemed convinced could pull off the complex nature of T E Lawrence – at once broody and recalcitrant, romantic and mystical, yet ultimately ambiguous and divergent.

The 30 year-old tearaway Peter O’Toole was in the incipient stages of cultivating a reputation of being a rabble-rouser, perplexing the funders as to why Lean would cast him over the likes of the more established Marlon Brando or Albert Finney. But they yielded to Lean on this one, settling to ensure that they held sway over the choice of Ali, Lawrence’s chief ally and friend.

For they, like Lean, knew that the character of Sheriff Ali was in many ways the moral heart of the film and an almost equally important role. Ali represents, in a single character, the ambitious hopes and nationalistic dreams of the entire Arab nation in the early twentieth century, seeking to throw off the yoke of colonialism.

While sharing Lawrence’s idealism and youth – young men, after all, are the ones who dream of change and who lead revolutions – Ali is a grounded counterweight to the politically naive Lawrence; the one who doesn’t lose his soul in the chaotic march of war as Lawrence’s Arab Revolt makes a headlong charge to claim Damascus for the Arabs. Both men are drawn to each other by a shared devotion to the desert – for each of them it represents something spiritual – “the desert is an ocean into which no oar is dipped.”

But unlike Lawrence, Ali is of the desert, understanding its undulating ebbs and flows and that its sand covers ancient tribal divisions which resist sudden attempts at closure. When the Englishman is asked by the mystified Arabs why he is drawn to the desert and he answers “because it’s pure”, you sense immediately that Ali, by contrast, knows that the pureness is but a mirage. And when an ultimately undone Lawrence flees Arabia, foiled by Anglo-French political machinations and the mercurial nature of the Arabs themselves, you sense that it is Ali who will be the one who will try to pick up and restore the scattered pieces of nationalism.

So why did Lean gamble on an unknown Egyptian actor, whose only experience in films had hitherto been in Egyptian fluff, to pull off this most hopeful of roles? Why was he prepared to fight the Hollywood producers yet again to get his choice, even though they had already given the contract to another actor of their choosing?

It’s worth remembering that Lean, for all his great filmmaking virtues, had a notable weakness – a product of European snobbery, he had an unwillingness to consider Oriental actors for such parts, preferring instead to give them to Europeans. “I can’t direct them [Orientals],” he would say. “They find it difficult to stand still, hold a look; they tend to exaggerate everything.”

Thankfully for us, David Lean was able to put aside some of that snobbery. Part of the reason, he would later recall, had to do with the Egyptian’s eyes. They gleamed like few others did, hinting at emotions hitherto unseen. And they shimmered like few others did too, suggesting depths of soulfulness. They were the eyes of a revolutionary, a doomed lover, a haunted wanderer, a beguiling raconteur – and a poet.

Part of timeless nature of Lawrence of Arabia, that most enduring of films and one called “a miracle” by a reverential Steven Spielberg, has to do with the character of Ali and the actor who played him. Omar Sharif, the Egyptian Coptic who died last week aged 83, will forever be associated with the role, along with his other great triumph with David Lean, that of the sensual and tragic poet Dr Zhivago who creates magical verse for Lara, the great but unrequited love of his life.

In both of these and his other prized roles, it was the eyes which set Omar Sharif apart. Those mesmerising eyes are what we chiefly remember all these years later. As the French film critic Agnes Poirrer theorised, they embodied “an explosive melange of suaveness and passion, of indolence and fire.”

Watch: Doctor Zhivago trailer

But the more perceptive viewers would also note that they seemed to hint at some other, hidden secret. Their perception would have been correct, for the actor was an artist of disappearance. Omar Sharif was actually a construct; similarly too the idea of him being a masculine and seductive Muslim Orientalist. He was born Michel Chalhoub in cosmopolitan Alexandria in 1932, the son of Melkite Greek Catholic family of Lebanese descent.

His mother was a noted society hostess and bridge partner of King Farouk; his upbringing representing the alluring mix of French, Hellenistic and English elements which the Middle Eastern elite of that period imbibed. He only took on his non de plume to make it easier for Egyptian audiences to pronounce his name – but for all that, it was the alluring mix with which he had been blessed as Michel which gave the dash of charisma to his performances

When Lawrence of Arabia was restored and rereleased in 1989, I was a young boy. I still remember being taken to the cinema on the opening afternoon by my filmophile father, and it was here that a dawning realisation of the power and magic of the cinema was born. Like millions before me, I was entranced – that is the only word to describe it – by the scene which introduced Omar Sharif to the world – that infamous, unnervingly brave long-shot where he arrives, mirage-like, out of the heat of the desert and into movie history. All the romantic qualities of the desert – of the silence, of the vastness, of the mystery – are captured here.

Having made such a dramatic entrance, how could Sharif possibly follow up Lawrence and Dr Zhivago? He couldn’t – and in truth he didn’t care much to. Years of drift followed, in which he appeared charmingly in undistinguished Hollywood films or in films which, even if they were not undistinguished, failed to showcase his full talent. The artist had disappeared yet again, into a breezy, elegant world of high stakes bridge (he became a world authority, even if in the process he lost millions), of soirees and horse-racing. He seemed to be good-humouredly cocking a snoot at those of us who wanted him to take his craft more seriously. “I’d rather be playing bridge than be making a bad movie,” he said, but for decades he seemed to be doing both with equal vigour.

He reappeared one final time, about a decade ago, to make a small, but important film. Monsieur Ibrahim is a wistful tale about the relationship between an elderly Muslim shopkeeper and a troubled young Jewish boy who both find meaning in their lives through their friendship. For our post 9-11 world, it’s a parable of tolerance and understanding between religions – and a film well worth watching for all those who believe that their religion alone holds the monopoly on truth. It was a film, he said, “about people interacting as people and not symbols” – and he made it to help his grandchildren understand this idea. As the grizzled but graceful shopkeeper, a keeper of beautiful thoughts and inclusive humanity, the elegant artist had belatedly returned – and this time the flames in the eyes danced again. It would be one final hurrah.

He died, after a long illness, in his beloved Cairo. The artist has disappeared for good. But at least we’ll always have the memory of those eyes. DM

Photo: Actor Omar Sharif speaks about his career at the American Film Institute’s “A Tribute to Omar Sharif” in Hollywood, California November 11, 2003. (Reuters)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider