Africa

Can the IMF save Ghana’s currency?

A cool $114 million has just found its way into Ghana’s struggling bank balance, courtesy of a new loan package with the International Monetary Fund. It’s not huge money in the grand scheme of things, but alongside the government’s own reforms – and with more IMF funds on the way – it could be just enough to rescue Ghana’s free-falling cedi and stabilise its wobbly economy. By SIMON ALLISON.

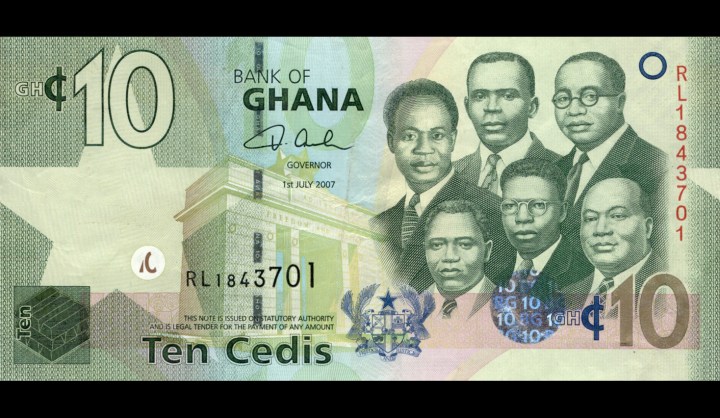

On Tuesday, the Bank of Ghana’s strained reserves received a boost, to the tune of $114 million, from the International Monetary Fund. It’s a tidy sum designed to shore up the rickety central bank and stabilise Ghana’s currency, the cedi, which has lost nearly 20% of its value against the dollar since the beginning of this year.

This swift depreciation is no anomaly, but the acceleration of a dangerous trend. Over the course of 2014, the currency lost about a third of its value, despite government efforts to halt the decline, and threatened the stability of the economy as a whole – which had been one of Africa’s most promising.

Tuesday’s deposit is just the first tranche of an extended loan facility from the IMF that will eventually be worth $918 million. It’s part of what is basically a three-year structural adjustment program that’s supposed to restore macroeconomic stability and sustain higher growth. Despite earlier promises to avoid IMF assistance, President John Mahama described the deal as good news for Ghana that would allow the country “to deepen our social protection intervention to help cushion the poor and vulnerable in our society”.

Ghana’s currency crisis has its roots in a decision to standardise public sector salaries – a decision inherited by the current government led by President John Mahama. The public wage bill ballooned dramatically, from 3.4 billion cedi in 2010 to 10.8 billion cedi in 2014, stimulating an explosion in imports that the country found very difficult to finance.

“After two decades of strong and broadly inclusive growth, large fiscal and external imbalances in recent years have led to a growth slowdown and are putting Ghana’s medium-term prospects at risk. Public debt has risen at an unsustainable pace and the external position has weakened considerably. The government has embarked on a fiscal consolidation path since 2013, but policy slippages, exogenous shocks, and rising interest costs have undermined these efforts. Acute electricity shortages are also constraining economic activity,” said Min Zhu, IMF Deputy Managing Director.

Initially, Ghana insisted it could fix its problems by itself, instituting a series of “home-grown” structural reforms. The government increased VAT, removed fuel subsidies and imposed a fuel tax instead, and introduced ad-hoc import tariffs and taxes on the financial sector. These worked, to an extent, especially in terms of narrowing the current account deficit. It wasn’t enough, however, and in August last year the government asked for international assistance, of which the IMF package is just a first step. According to financial analysts, it is likely to be followed by deals with the World Bank and the African Development Bank, as well as the issuing of a World Bank-guaranteed Eurobond.

Stephen Bailey-Smith, head of research for Africa at Standard Bank, says he is optimistic that the measures being taken by the Ghanaian government, including the IMF deal, are the right ones. “The finance minister is actually an ex-IMF official, he spent ten years on the IMF giving advice to countries on fiscal policy, so he’s very well-versed on what the IMF would need and expect to get out of this conundrum,” he told the Daily Maverick.

Bailey-Smith added: “Ghana has been growing very swiftly, and the economy is moving albeit in an unstable fashion. So if you’re talking about foreign direct investors, in the tourism sector or construction or retail, that part of the economy is starting to move again. If anything, the economy had been overheating and I think we’ll have a more normalised growth process going forward… Longer term I’m fairly constructive on Ghana emerging as a reasonably prosperous society, and I think getting that stability back into the financial sector will assist that process.”

Ghana’s main opposition party, the New National Party, isn’t so sure. National organiser John Boadu criticised President Mahama for resorting to IMF assistance – and, therefore, IMF regulations – for what he described as a relatively trifling sum, one that football clubs spend on top players. “You have run the country to a point where there is nothing to do but to borrow…money which can be used to transfer a Chelsea player…I see Ghana as a rich country. We are not poor and so I get surprised when things like this happen.”

For the record, Chelsea’s most expensive signing is Fernando Torres for $80 million, while football’s most expensive player is Gareth Bale, for whom Real Madrid dished out $123 million. This isn’t quite enough by itself to rescue the economy of a mid-size African country, although – alongside Ghana’s own reforms and in anticipation of the tranches of cash – it should certainly help. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider