“Welcome,” TRC Commissioner Dumisa Ntsebeza told a witness at a hearing that took place in Cape Town on 2 June 1998.

“I have explained very quickly to most witnesses that this is a Section 29 enquiry. What it means is it is an investigative enquiry. It is not a trial, it’s not a tribunal, it’s not disciplinary enquiry, no findings will be made. It’s an information gathering exercise,” Ntsebeza said.

“It is held privately so you can safely regard everybody here to have been sworn to confidentiality and so also will the evidence that will be taken here to not be made public and that decision will be the decision of the Commission as and when certain requirements have been complied with.”

This is part of the record of the TRC inquiry into the Helderberg plane crash. That inquiry was one of a number of hearings held, under Section 29 of the TRC act, in-camera rather than in open view. The idea was that those testifying would be more incentivised to give full and free information if the hearings were held confidentially, and without any threat of a subsequent criminal charge.

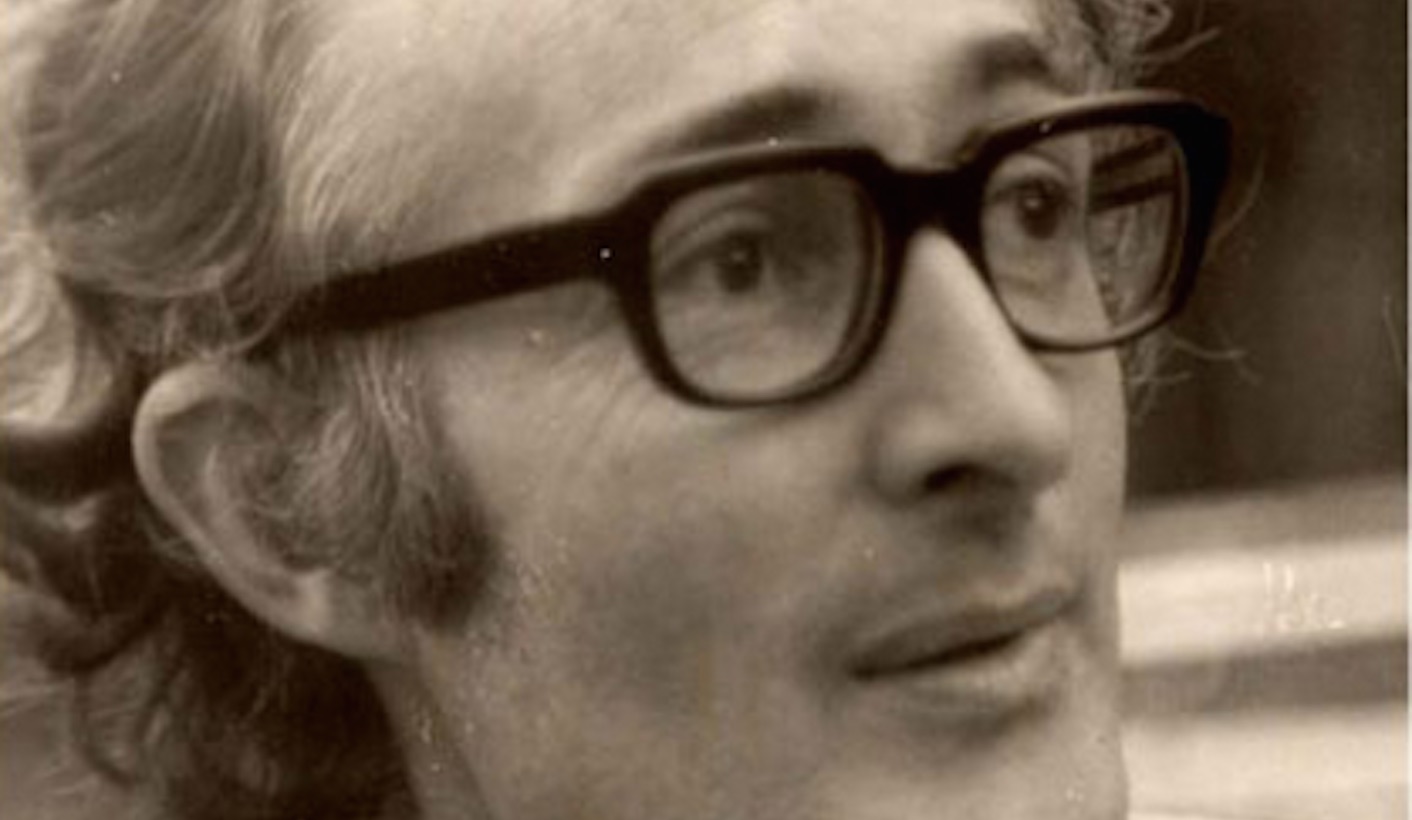

Individuals giving testimony at these hearings were under oath, however, and could be prosecuted for perjury. They were people suspected of having knowledge of “some of Apartheid’s most heinous crimes,” to quote the South African History Archive (SAHA): the crash that killed Mozambique’s president Samora Machel; the deaths of anti-Apartheid activists like Rick Turner and Griffiths Mxenge.

The Helderberg inquiry records were subsequently released in full, as were the transcripts of a number of other Section 29 inquiries. But many others have stayed classified in the years since the hearings took place. SAHA, in fact, doesn’t know exactly how many records may be in existence.

“We don’t know what we don’t know,” SAHA’s Right to Truth researcher Robyn Leslie told the Daily Maverick on Tuesday. Leslie says that SAHA has for the last 11 years been working through its vast TRC document archive in order to try to collate a list of all the Section 29 hearings held by the TRC.

From 2001 onwards, SAHA began lobbying for the records of the confidential hearings to be made public, maintaining that the raison d’etre of the TRC necessitated this step.

“The public nature of the TRC was widely lauded as one of its most important features,” Leslie explains. The TRC’s mandate of helping the South African public come to terms with the past demands that gaps in information be filled as much as possible, SAHA has argued for over a decade.

In 2003, SAHA launched a Promotion of Access to Information Act (PAIA) request for the transcripts of five specific closed hearings. They included the hearing into Craig Williamson, the Apartheid spy who was involved in the murder of Ruth First in 1982 and the bombing of the ANC’s offices in London in 1982. They also included the hearing into the murder of Stanza Bopape, the Mamelodi activist who died in police custody.

The Department of Justice denied SAHA access to these records. They went on to deny SAHA access to all such records, when a request for the full archive was launched in 2006.

“SAHA used PAIA to access these records – a legitimate, legal request, which the Department of Justice consistently and counter-intuitively rejected,” Leslie says. As a result, the matter went to court.

TRC Commissioners wrote affidavits confirming that they had agreed near the wind-up of the TRC that the public should subsequently be able to access the Section 29 records, subject to certain conditions.

The Department of Justice argued, however, that the release of the transcripts would “constitute an unreasonable disclosure of highly personal information”, and that it might harm the “reputations and dignity” of individuals involved.

The Department of Justice also contended that confidentiality had been guaranteed to those participating in these hearings, and that the subsequent release of the transcripts would constitute a breach of the department’s undertaking. The Department was also concerned that the release of certain records could negatively affect ongoing investigations by the National Prosecuting Authority.

SAHA successfully challenged this reasoning, arguing that since 2009 the NPA had not launched an investigation into a person implicated in the Section 29 hearings. Moreover, confidentiality as to the content of the hearings was only guaranteed at the time, not indefinitely.

SAHA won: at the end of 2014, the archive took possession of 174 records from Section 29 hearings. Leslie describes it as a “vast” volume of material, which still has to be processed. When this is concluded, the records will be publically accessible online.

We don’t know what’s in the transcripts yet. “Some information is definitely controversial,” Leslie says. “Allegations and denials abound as much in the [Section 29 hearings] as in other TRC proceedings, and some of it will be new to the public.”

SAHA believes the wider significance of its victory in this matter, however, lies in the principle of access to information. Compliance with PAIA, Leslie points out, is a duty rather than a choice. “The [Department of Justice]’s 11-year rejection of the central tenets of SAHA’s PAIA reflects very poorly on the department that is both the originator and custodian of PAIA, and the government body that houses the TRC unit,” she says.

“Throughout its lifespan, the TRC repeatedly highlighted that its records should be made publicly available to the greatest extent possible. The TRC also stated that its work was merely the beginning of what should comprise many further years of research, investigation and publication, in an attempt to develop as complete a picture as possible about our past.” DM

For more information on SAHA’s work, visit: www.saha.org.za

Main Photo: Philosopher, academic and anti-Apartheid activist, Rick Turner who was assassinated in 1978. No one has ever been charged for his murder. (Picture Jann Turner)