South Africa

Review: Raymond Suttner’s Recovering Democracy in South Africa

J. BROOKS SPECTOR has read political philosopher Raymond Suttner’s latest book, Recovering Democracy in South Africa, and contemplates the author’s call to arms to reclaim the nation’s democratic processes from those who would traduce its proud antecedents of struggle.

Over the years, Raymond Suttner has become a social and political conscience for the heirs of the liberation struggle. Increasingly, this has made him into a kind of class scold, warning of things others do not – or chose not to – see just yet. That role seems to have gradually come Suttner’s way after his long service in the liberation struggle on behalf of the African National Congress (ANC) in underground activities, tasks interrupted by periods of imprisonment and interrogation. Post-1994, he has engaged in steady writing, teaching and lecturing, as well as periods as an MP and as South Africa’s ambassador to Sweden on behalf of the new government.

In this, his newest book – following earlier volumes, Inside Apartheid’s Prison and The ANC Underground – Suttner’s Recovering Democracy in South Africa brings together a collection of his short writing published over the past decade, albeit mostly in the past several years. Most of these appeared on the Polity website as well as in a number of other places (including essays in Daily Maverick. Moreover, as a sign of the times, the book also includes QR links (those black and white chequered squares about two centimetres square) so that readers with smartphones can access and view recordings of interviews conducted over the past four years. These interviews have been specifically selected so as to supplement many of the essays in this volume.

Suttner’s newest book comes along as part of an increasing stream of books that offer diagnoses of the country’s problems and often proffer a variety of cures for those ailments. In different ways, recent works such as Max du Preez’ A Rumour of Spring, Richard Calland’s The Zuma Years, Raymond Parsons’ Zumanomics Revisited, and Adam Habib’s South Africa’s Suspended Revolution: Hopes and Prospects all provide useful, thoughtful insights into the notations on South Africa’s patient chart – as well as the procedures that must be carried out and the prescriptions that must be taken as soon as possible.

If du Preez’ is a highly personalised version of his hopes (and fears) for the social glue that holds South Africa together (or keeps splitting it apart), Calland’s volume is an analytical set of x-rays (to continue the metaphor) of how power works – and who holds it in the many different institutions of Jacob Zuma’s world. Meanwhile, Habib’s contribution offers a range of prescriptions in accord with something like the standard treatment protocols of social democratic theory and practice. Finally, Parsons’ book speaks about the need for serious economic discipline to begin to approach that mooted developmental state, as well as continuing, careful attention to the economic fundamentals. Taken together, they offer a comprehensive look at the machinery of “a dream deferred” in many ways, and what must be done to fix things, albeit with the occasional soupçon of hope for better things yet to come and an embrace of the South African genius for straddling seemingly impossible divides.

Several things make Suttner’s volume rather different than these others. For one thing, rather than a consistent narrative, this book is a collection of short essays grouped together around thematic choices. These essays are often less than three pages long. Nevertheless, they critically examine the style of Zuma politics as well as the twists and turns in South African considerations of gender, sexuality and race in contemporary politics. In particular, Suttner focuses on the relationship between Zuma’s political style, his rootedness in traditional culture and what that means, especially the ideas of the warrior and masculinity, trying to tease out just where and how the Zuma political code derives its strength and resilience under pressure. In light of Zuma’s performances in the recent parliamentary debates, these chapters may have special relevance for close observers of South African politics.

Because the essays were designed to reach varying audiences over time, reading the book straight through can sometimes provoke thoughts that the reader has just explored that same point from a slightly different angle a few pages earlier. Perhaps a deeper rewrite of some of these essays would have produced a more seamless, less seemingly repetitive sense of things. However, such an approach might well have defeated the point of presenting a full body of writing (unretouched) on what has, over the years, been a kind of layman’s tutorial on practical political philosophy.

But, as Suttner delves into questions of the nature of leadership and importance of ethics for leaders in the latter sections, the volume takes wing as a primer on moral philosophy in political life. Throughout, the author has remained steadfast in his respect for the Mandela spirit in politics. But this is not the one-dimensional secular saint who was kind to children and pets who has become so common in the usual gauzy hagiography. Instead, Suttner’s Mandela was an intensely political leader who managed adroitly to co-mingle a struggle for “ends” with “means” – even as such efforts failed to traduce his deeper values.

Or, as Suttner writes, “Among the legacies of Mandela is this ethical core, this sense that acting on beliefs involved not merely the enunciation of ideas, but a preparation for and a willingness to endure hardships of an extreme kind. It is possible that some who read this will say that this is something for Mandela, not for us ordinary mortals. But all of us, in our everyday lives, confront difficult decisions and we have to decide whether or not we should act in accordance with the beliefs we claim to cherish. It is this unity of thinking acting that we need to try to incorporate into our personal and political life.”

When the author reaches the final three selections in this book of essays, however, he has largely shed an earlier, more even-tempered voice. That style generally did not push the writer’s language beyond a tone of civility and balance – with words chosen carefully to avoid giving vent to a deeper rage and anger. But at the latter point in the collection, Suttner has effectively embraced what might have been called Cincinnatus’ exercise of those ancient Roman virtues of self-discipline and self-sacrifice for the greater good. As a result, it is not very difficult to see whom, by contrast, he has in his metaphorical gunsights.

Suttner argues, “My principal argument in all the essays that appear here is to suggest that this is not the time to foreground doctrinal purity of any type but to seek collaboration with a range of concerned citizens to restore legality and constitutionalism and to recover the democratic and transformational values of 1994. In general, I support the idea of a united front, though what I advance here may be wider and more inclusive than what is envisaged for instance by the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (Numsa).” There is nothing like putting one’s cards on the table in this way to make a point.

In arguing for this position, Suttner is really drawing attention to the argument that South Africa’s democratic revolution has, too often and in too many ways, become an exercise in “electionism”, rather than the practice of real democracy. What is needed now, instead, is a return to the broader participatory urges of the old mass democratic movement, trade unionism that rose up organically from the shop floor, as well as a reclaiming of a sense of engagement by the many in communities, rather than the awkward and unsatisfactory way disaffected citizens must now largely engage with a bureaucratic, and often unresponsive octopus of a government.

One short essay towards the end of this volume – “Does parliament represent the people?” – is the kind of discussion on the nature of formal parliamentary representation and the tensions between that approach and all the other ways citizens can articulate their concerns, angers and desires deserves a wide readership among all who concern themselves with nature of the contemporary political system. Suttner’s conclusions are significantly at variance with those of, say, Edmund Burke in his ‘Speech to the Electors of Bristol’, who had focused on the need for representatives to be true to their own sense of values and virtues rather than the simple-minded act of blindly following party or voter preferences.

Instead, true to his own radical heritage, Suttner argues for a way South Africa’s current parliamentarians can measure their real, lasting success when he writes, “Any project aimed at safeguarding and enlarging the scope of our freedom needs to represent the interests of all, wherever they are located, and whatever the conditions in which they live. Unless one speaks to their location, one is not offering a radical programme, no matter how an organisation describes itself. In erasing the life experiences of many who fall outside organised formations, one negates the idea of a broad emancipatory project.”

Recovering Democracy in South Africa is the kind of book people should savour slowly, dipping into it over time. The author’s prose – whether it is in his efforts at even-handedness in many of the earlier essays, or from the increasing anger that finally comes out in the last third of the volume – is always crisp, clear and precise. The reader always knows exactly what Suttner has meant by his sentences, even if one disagrees with either his conclusions or his arguments.

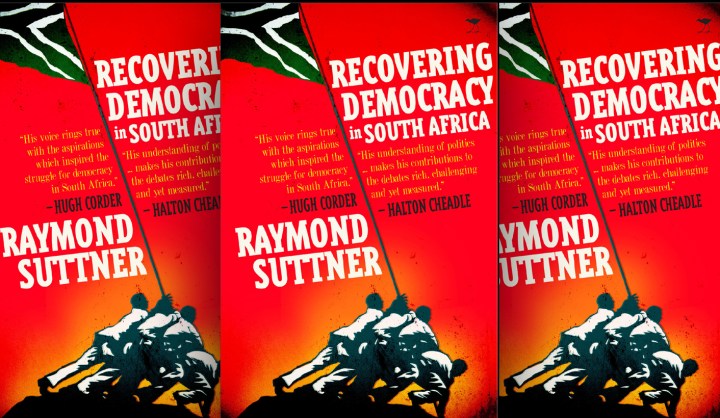

One curious question lingered in the mind of this reader, however, after reading the book. The book’s cover is a fascinating appropriation and reshaping of the image of that famous statue of the US military’s raising of the US flag on Mount Suribachi during the battle for Iwo Jima that is the official US Marine Memorial in Arlington, Virginia. The statue was itself modelled on the photograph taken of that moment in battle by AP photographer Joe Rosenthal. And so a question lingers: Was the use of this graphic a hidden (or perhaps not so hidden) message to inspire a serious struggle to reclaim South African democracy from those who would crush it? DM

Recovering Democracy in South Africa, by Raymond Suttner, Jacana Books, ISBN 978-1-4314-2158-9. The book is also available as an e-book in various formats.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider