South Africa

Sibanye Gold’s Hlanganani shaft: Going deep into the heart of the economy

Not many Cabinet ministers are venturing underground to see how mines really work, and there’s a lack of political support to ensure that costs are kept down. Without such support, it’s difficult to imagine a real, long-term future for the industry – when it costs R15 billion to sink a 1.5km shaft. Illegal mining is already a worrying indicator of the extent of the unemployment problem. What’s really going on at ground level in the mining industry? GREG MILLS pays a visit to Sibanye Gold’s Hlanganani shaft.

Henry Barnard, 48, is the mining manager on Sibanye Gold’s ‘Hlanganani’ shaft at its Driefontein operations, near Carletonville. Once known as ‘number 5’ shaft, the new name (meaning ‘come together’) reflects Sibanye’s own translation as ‘We are one’.

Sibanye was created in 2013 from an unbundling of Gold Fields Ltd. Sibanye’s initial three mines were considered deep, high-risk, labour-intensive operations with a limited future.

Today that future looks brighter, thanks to the trimming of costs and getting labour and the local communities more on board.

“We were able to take the assets performing badly in Gold Fields’ hands and turn them around in two years,” says Sibanye’s CEO Neal Froneman, “into the best performing gold share internationally. We were able to do this because we have tabular ore bodies with good grades that are extensive, and because we were able to get our costs down. With 55 percent of our costs in the form of people, we ‘displaced’ 7,000, but saved 35,000 other jobs in the process.”

And Sibanye now engages directly with the communities in which they operate. “Instead of building schools that we then handed over to the municipality to hand over to the community, while crowing how little the mining companies do for them, we now deal directly with these communities. We need stable and supportive communities, without which we don’t have a viable business,” says Froneman.

There is much still to be done.

Henry Barnard wanted to be a doctor like his famous heart-surgeon uncle Christiaan. But with his father a miner in Barkly East and, later, Kimberley, and not many opportunities for expensive education among him and his 14 siblings, the die was cast. “It was before TV,” he jokes of the Barnard Bunch. He has spent 31 years on the mines, all bar the last three of them full-time underground.

Barnard has worked only at two mines: first at Anglovaal’s Hartbeesfontein and then, from 2005, Driefontein. Such longevity is today unusual in an industry blighted by closures. Where Anglo American, for example, once ran 45 gold mines, today it runs just five. The rapid decay of Welkom, once the epicentre of the Free State Goldfields, confirms what happens when mines close – it rips the heart out of the local economy.

Some 52,000 tonnes of gold, 30 percent of global output, have been mined over 126 years from South African mines, with a peak of 1,000 tonnes in 1970, 70 percent of world production that year. Now, production has fallen to 167 tonnes. Though gold is still (after platinum) South Africa’s second largest mineral export and mining employer, with 130,000 workers, this is way down on the figure of 540,000 in the mid-1980s.

In part, the difficulties experienced since then relate to the changing role of the unions and salary structures in a business where, today, electricity and staffing costs comprise 75 percent of Sibanye’s costs.

Despite the pruning of numbers and attempts, now, to build solar energy alternatives to its 550MW needs, the cost structures are fundamentally difficult to change. Underground it’s much the same drilling, blasting, digging, and scraping operation it was a hundred years ago, albeit somewhat more efficient and much safer, despite the depths and the increasing logistical complexity in getting people down and ore out from the working stopes to the gullies; into trains down the ore-pass and up to the surface in skips, where it is crushed and refined. Getting the ore out is much easier said (or written) than done.

Driefontein’s number five shaft operates today at five levels (numbered confusingly 42, 44, 46, 48 and 50), all of which slope to follow the 23o slant of the gold seam. To get to 42, 3.5km underground, we took two separate lifts, limited by the length (and weight) of the cables to around two kilometres in depth, and capable of stacking 45 people in each of three decks. Descending at more than 10 metres per second, four times the speed of a normal lift, we were soon at the tram to take us two kilometres to the working panels.

Part of the drive for greater efficiencies has involved increasing the time the miners spend at the rockface, including decreasing the duration they would spend walking in and out, to and from the lift cages.

It’s a tough man’s and, increasingly, woman’s game underground – the latter now making up five percent of the Sibanye workforce. Around half of workers are South African (mostly from the Eastern Cape), and the bulk of the other half is made up, in order, of Basotho, Batswana, Swazis and Mozambicans. “Many of the drill operators are Basotho,” says Shadwick Bessit, Sibanye’s senior vice president and technical head, “perhaps the hardest job of all.”

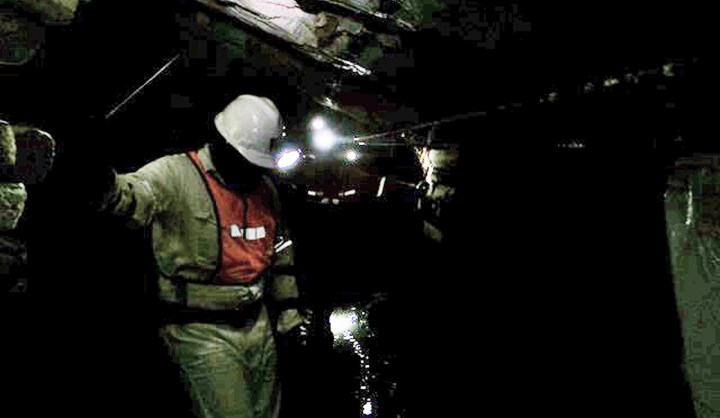

We walk down an increasingly narrow centre gully, scramble up a ladder and along a laddered incline, hard hats bumping against the low hanging wall, and we are in the strike gully leading to the working panels, along which are carefully stacked timber packs, bolstered by a pre-stress plate, and steel pillars, one or two already partially bent under the load. Overhead the gunnite reinforcing of the larger gullies is quickly replaced by meshing and netting, attached through stabilising roof-bolts fixed with cement up to 2.4 metres deep into the rock.

It’s a small place for big men, the drill operators sitting or crouching in areas little over a metre high, kneepads and elbow-guards grazing the surface, the light battery pack and bulky self-contained rescuer banging against hip and rock. The lower the stope, the less the dilution of reef in the rock mined, the higher the grade and the lower the mining cost. Though the reef, such as the rich ‘carbon leader’ around Driefontein, is sometimes just 30cm wide, there is still a need to mine at a height of 1.2m “just to get people in” says Bisset.

It’s not easy going. Turn the lights out, and you would not see your hand in front of your face. With the virgin rock at 50 degrees Celsius at these depths, the miners are drenched in sweat despite the bulk air cooling.

There are 2,800 miners down and up the number five shaft every day. They send up 3,500 tonnes of ore daily. From each tonne is extracted between six and seven grams of gold.

Reflecting the trimming of management above ground, Driefontein has managed to improve productivity (measured in square metres mined per 19 person crew per month) by 40 percent. This has seen the cost per tonne mined drop from R2,600 to R1,600, increasing the mineable reserves from 13.5 million to 20 million ounces in the process. “As the ‘pay limit’ [aka, the break-even point] falls,” notes Bessit, “our life of mine gets longer. Unless we keep reducing our overheads, especially personnel, eventually we will have to close even though the resource will not probably be depleted.”

William Osae is Driefontein’s head of operations. A Ghanaian by birth, he has decades of mining experience across southern Africa and various mineral types. He says that “[t]he unions spend a lot of time talking about wage increases, but hardly ever talk about productivity increases. There needs to be better balance” to ensure long-term prosperity of the industry.

Without political support in their attempts to keep costs down, it is difficult to imagine such a long-term future where it costs R15 billion to sink a 1.5km shaft, which will take 10 to 15 years to pay back. Absent business confidence to invest for the long-term in the ultra-deep, the reserves will remain there. And the costs of not achieving Osae’s “better balance” will be seen in further unemployment in Carletonville, an area already hard hit by mine closures. The extent of illegal mining, with an average of more than one arrest every day on Sibanye’s operations, is one indicator of the scale of the unemployment crisis.

How many Cabinet ministers have ventured underground, in the practical and not metaphoric sense? If they did, perhaps it might stimulate some thoughts on how to use policy to make it easier for employers.

South Africa still has the biggest gold reserves world-wide. With better policy, including government using the tripartite alliance to deliver a peace dividend into the workplace, these could be a long-term resource for jobs and the fiscus. Henry Barnard’s eldest son is training to be a Chartered Accountant. “But the other one,” he smiles, “wants to be an engineer on the mines.” Government’s challenge is to make it possible for him to do so. DM

Dr Mills heads the Johannesburg-based Brenthurst Foundation and is the co-author of the forthcoming ‘How South Africa Works – and could do better’ (Pan Macmillan)

All photos by Dr Mills.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider