World

Diploma Mills and other millstones around South Africa’s neck

The chaos and damage caused by the misstatements made by a number of South African diplomatic representatives concerning their educational attainments encourages J. BROOKS SPECTOR to contemplate what this means and how to fix it.

The scene always had a sad sameness to it. First there was the pride at having achieved a university degree from the US. Then, as the explanations began, then came the pain, the shame and embarrassment. While working abroad, this writer frequently supervised embassy and consulate educational advisors – locally hired individuals who had a significant background in teaching and studying in America. They were also often foreigners who had gone through the complicated process of gaining admission to an American university, sorting out the financing of that education and then graduating successfully, after hard study.

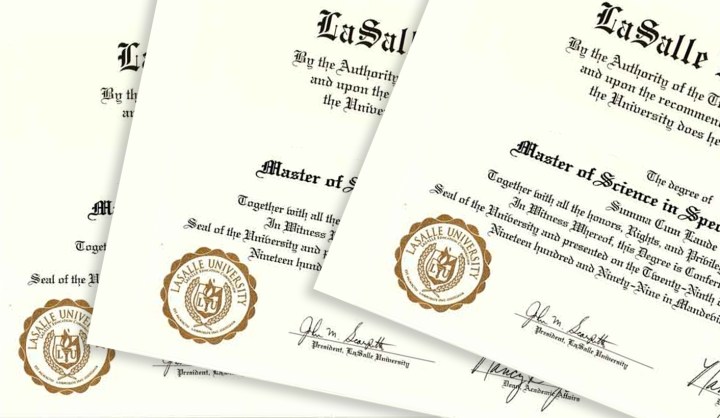

Besides explaining the astounding realities of financing a degree in the US (the total cost for study at places like Harvard, Stanford, Yale, or Georgetown Universities can now easily surge past R500,000 per year while still existing on Spartan rations), one of the hardest tasks for educational advisors was dealing with individuals who came in clutching diplomas from fly-by-night diploma mills, and who wanted reassurance they had made a good investment in their education. They would inevitably show ornate, beautifully engraved diplomas, a file of receipts and some substantial cancelled cheques, as well as a letter on rich-looking, sturdy foolscap paper promising they had successfully completed the requirements for a BA, a BS, an MA or a PhD at the University of X. Moreover, their achievement marked a significant point in their professional careers. Then the problems would begin. The tears might well start to flow at the moment the bearer of these items heard their certificates effectively were worthless, and virtually fraudulent.

The problem, simply put, is that while there are over three thousand fully accredited universities and four-year colleges across the entire US, there are also a number of very dubious, fly-by-night diploma mills – schools that are, effectively, often little more than a post office box, an administrator or two, and, most important of all, a bank account and a billing office.

The problem for many foreigners is that the American educational system can seem very complicated. It is also significantly beyond intensive regulatory purview by the national government. In fact, the national government directly only administers a handful of universities, the four service academies and a unique university for the deaf and a few other study programs. Everything else is either privately organised (either as secular or church-related institutions), or managed and established by the country’s various cities, the fifty individual states and thousands of counties.

Instead of constant federal oversight, universities and colleges are usually accredited – that is, effectively given a stamp of approval as legitimate educational entities – by one of a number of regional accrediting bodies that divide up the country into multi-state groups, as well as professional accrediting bodies that usually focus on individual fields such as the engineering disciplines, the various medically-related fields, legal studies, the hard sciences, and so forth.

In addition, of course, there are often state licensing bodies in the various states that have been largely set up to issue operating licenses to many private, smaller institutions as businesses. But, crucially, these state government offices are not, largely, concerned with the actual educational quality of the institutions they license.

As a result, the diploma mills have found this is a niche they can use too and they usually advertise themselves as licensed by the State of X. Their promotional material will proclaim their degree holders now hold well-paying, prestigious and influential positions in business and government – and around the world. However, they won’t mention anything specific about their actual accreditation – and that’s the magic phrase.

Traditionally, American higher education institutions required in-residence education for all their degrees. This included the usual round of classes, and lab or practical work in the chosen field, as required. This usually meant four years for a first degree (the US does not do honours degrees); frequently two years to complete a master’s degree, and then several years of fulltime study or more to reach a doctorate, depending on the topic and discipline. Medical and legal degrees in America come after finishing a first degree.

However, in recent years, there has been a fantastic growth in a wide variety of online education opportunities, as hundreds of universities have offered an increasing number of their usual courses or specially designed ones online – and even degrees that largely consist of online course work. Generally such programs also require some in-residence periods over the course of that degree. Still other schools have built up programs that provide major portions of a degree for lifetime experiential learning. Key here is that such credit comes upon submission of an extremely detailed portfolio documenting real learning efforts (such as work in the chosen field or mastery of a foreign language), as well as examination of portfolios by professors at the university concerned.

However, to the best of this writer’s knowledge, no legitimate American university simply awards a degree on the basis of a simple commercial transaction – that is, a substantial cheque handed over in return for the coveted sheepskin. And any such degree claimed would be extremely unlikely to help an applicant apply to another school for a further degree, or even to transfer any credits (those measured units of study of a subject over a half year) to any real, accredited school.

And that, of course, takes us, inevitably, to South Africa’s newest scandal. In recent days, South Africa has been hit by not one but two burgeoning embarrassments. The South African Ambassador to Japan, Mohau Pheko, and the country’s newly accredited Ambassador to the US, Mninwa Johannes Mahlangu, both list degrees from American universities that no longer exist. Further, by all accounts these two schools were simply your garden variety diploma mill, accepting those juicy cheques and cranking out those sheepskins.

In Ambassador Pheko’s case, her PhD from La Salle “University” of Louisiana had already been unmasked when she was high commissioner to Canada, back in 2010. As a result, she was pressed to drop such a claim from her bio. For their part, the Canadians largely ignored her, given this public indiscretion. Then, when she headed off to Tokyo, the PhD inexplicably reappeared in her CV. Now she has been pressed by the embarrassment to issue a wide-ranging, the-bad-dog-ate-my-diploma, the-devil-made-me-do-it, it-was-all-the-other-guy’s-fault, hand-wringer of a statement, effectively blaming everything on the now-vanished school and her heavy work schedule.

Her apologia, said, in part:

“LaSalle University was promoted as a legitimate university when I was registered to study almost 20 years ago. It offered the flexibility of schedule that was a desirable option for me at the time. Without the proliferation of information in the internet now available, I had no reason to believe otherwise. It operated like any normal university with technical assistance, supervisors and professors who were rigorous in assessing the work and responded and supported students. Legitimate money was spent on admission and registration fees, and a supervised thesis was completed. I regret that despite doing all the work necessary to fulfil this work, questions at the end arose on the corrupt practices of the administrators of the university. At no time were we informed that our academics were in danger.

“The PhD was awarded by LaSalle University. Immediately after notice letter of completion problems began when final transcripts and final award were not forthcoming.

“If I could have predicted the outcome would I have taken this route? No! Hindsight is always better. With more information I would not have registered there.

“Should victims of these institutions be allowed to use their titles? Rigorous work was done, and the work was supervised by legitimate professors. If I have aired in judgement I deeply regret that. Many from LaSalle University continue to use PhD titles because the normal course of work was done and have a relationship with their employers who believe they are competent and capable of doing their jobs….

“I used the title because I was blind-sided by my anger at the injustice of using my savings, working in a rigorous program that was undermined by those who sought to make profit out of genuine students who needed the flexibility of an online program….

“I was blind sided by my anger at the injustice of having worked towards an academic credential which was undermined by those who sought to make a profit. I shall forthwith withdraw any usage of the title while I weigh my options. I hope this can serve as a cautionary lesson to millions who seek to advance their academics. I welcome the debate, it is an important one as officials at all levels are held to a higher standard in our society.”

Nowhere in all of this finger pointing has the senior diplomat offered to allow anyone to read her dissertation – or see any examples of her course work. No looks at grade slips, term papers – or any other evidence of having actually done more than participate in a commercial transaction between a willing seller and a very willing buyer – save by her say-so.

In all of this, two things now seem clear. First is the fact that this Louisiana diploma mill appropriated the name (and perhaps even some of its reputation for the more credulous) of a long-established university with the same name in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. THAT La Salle University is an excellent school – and it has often had a great college basketball team too, just by the way. The second point is that the State of Louisiana seems to have had a particularly loose-limbed approach to handing out business licenses to diploma mills. This latter point thereby leads to the second case at hand – that of Ambassador Mahlangu and his claim to have received a bachelor’s degree from something called Fairfax University – which just happens to have been yet another diploma mill that just as coincidentally was also operating from the State of Louisiana. The ambassador had faithfully served, up until his appointment to represent South Africa in the US, as Speaker of the National Council of Provinces and as a long-time governing party stalwart at various lower level positions.

Interestingly, it turns out that in recent years a very real University of Fairfax has been accredited. But this school offers advanced degrees in highly technical IT and computer sciences, but not the bachelor of arts degree, a BA. Moreover, this school is located in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, DC, a location where it can easily draw upon a horde of highly skilled information scientists and another herd of eager students, often government employees, for its programs. All of these programs probably take place under the gimlet eyes of human resources professionals who must certify such degrees as appropriate for helping employees or would-be employees qualify for high-tech professional positions. Not too surprisingly, the Fairfax “University” in Louisiana, just like that other Louisiana school, is now out of business.

When South Africa’s Department of International Relations and Cooperation’s spokesman was asked about these claims by DIRCO senior officials, he was only prepared to offer a “no comment” – no matter how the question was asked. However, other sources did offer further information that these cases are in fact receiving high-level examination and review within the department – presumably to deal with these two cases and to prevent situations like these two to embarrass the government and country in future. The spokesman and others have hastened to add university degrees are not a sine qua non for appointments to ambassadorial level posts. Quite so. Being an ambassador is not the same as being a research chemist or tenured professor at a major university. Instead, a wide-ranging background and substantial experience with complex issues and high-level challenges nationally and internationally are the most important job requisites.

This is the kind of background that well describes a whole series of former South African ambassadors to the US who served at the end of apartheid and the beginning of democratic rule, people such as the late Harry Schwarz, Franklin Sonn and Barbara Masekela, who all served with distinction. The key was the dignity and gravitas of such people when they served in that crucial post. Looking beyond the current controversies, by contrast to the two in question, the biography of SA’s current High Commissioner to the UK, Obed Mlaba, makes no claim to any university degrees. The CVs of various other ambassadors and high commissioners cite easily verifiable study or degrees at universities in South Africa such as Ft Hare, as in the case of the country’s Ambassador to Germany, Rev Makhenkesi Arnold Stofile. And Amb Rapulane Sidney Molekane, now serving in France, in his CV, simply notes studies at the former Soweto College of Education (now part of the University of Johannesburg), making no claim to advanced degrees from any mysteriously vanishing universities.

But whence comes the root of these slippery claims to degrees from non-existent universities? Does it stem from some sort of deep sense of inferiority or inadequacy that a person’s real deal is just insufficient to impress under the glare of the bright lights of the big city? Or is it simply an affectation that, seemingly like many things nowadays, a degree is simply one more commodity to be acquired for personal benefit or from desire? Or, perhaps, is it a sense that South Africa so respects the idea of a title – after all, lots of South Africans with honorary degrees have long insisted on being introduced as doctor this and doctor so and so at every public event – that any old degree will do, even if it was just something paid for after being invoiced. Can this urge be tamed, this itch be scratched?

At least for American degrees, it should be relatively easy to contact an education advisor at the US Embassy or its various consulates, where a would-be student can check the bona fides of a potential place of study. Of course the Internet makes it still easier to do this, as long as one looks for the tell-tale indications of actual accreditation. In any case, advisors have been on staff for decades, well before the Internet revolution. These advisors have the tools to help students who wish to study in America or through a distance-learning program based in the US to sort through their options. And perhaps, more importantly still for our purposes today, accessing such information could help private and government employers clarify whether a school noted in a CV for a major, senior appointment really represents what has been claimed for it. DM

Photo: LaSalle University diploma from 1999.

Read more:

- Helping South African Students Study in the USA at the US Embassy website;

- Council for Higher Education Accreditation, the website of a non-governmental clearing house on accreditation;

- PREPARE FOR MY FUTURE – Diploma Mills and Accreditation – Diploma Mills, at the US Department of Education website.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider