Maverick Life

China’s Second Continent: A guide to the new colonisation of Africa

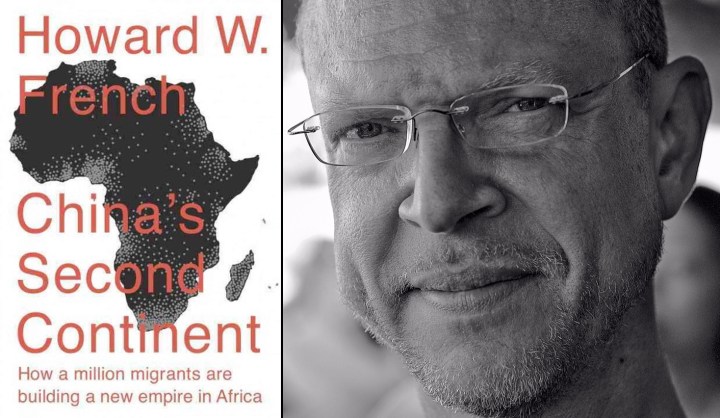

This period between Christmas and New Years Day in South Africa was a period of sorting and weeding out of decades’ worth of documents and records, as well as a start on a mountain of books that have been waiting for the quiet times. Far and away the best book this writer read was Howard French’s extraordinary record of discovery about the way as many as a million Chinese are now making their fortunes and futures in Africa. J. BROOKS SPECTOR takes a look at this important book that should be on every economic policy maker’s reading list.

Every once in a while, an author produces a work of reportage mixed with thoughtful analysis that can change the thinking on a question – or even rewriting the nature of that question. There is already a veritable mountain of books about the rise of China and its impact on the global economic future, and there is much in these volumes that demands the attention of serious readers. But one new book, in particular, Howard French’s China’s Second Continent, offers a very different – and provocative – perspective on China’s economic future, with special attention on Africa. Building on years of experience in both China and Africa, and following months of personal inquiry across the continent to search for answers to the questions of what China really wants in Africa, and how it is going to get there, French has effectively turned these questions on their head.

Instead of writing about China’s international economic policies in the language of the think tanks, of Wall Street and The City, or government councils in Whitehall or Washington, French has focused instead on what a million individual Chinese have done – or are now doing – throughout Africa, almost without regard to what the Chinese government may have planned or been thinking. In tackling the topic through this optic, French has given this vast Chinese movement into and across Africa crucial human dimensions.

Moreover, he has allowed this movement to be seen amidst much larger and longer-term historical and economic trends – rather than reducing them to the results of particular Chinese government investment or foreign development or foreign policy decisions. This re-calibration makes French’s observations all the more pertinent, startling with their granular clarity and that much more important to understand.

French is thoroughly acquainted with Africa. He was partially brought up in on the continent as a child, his wife is Ghanaian and he knows the region from the years he spent in Africa as a foreign correspondent as well. Moreover, he has also spent much time in East Asia where he covered developments in China (and speaks and reads that language well) and this writer met him years ago when he was covering news events in Tokyo as well.

In particular, French’s Chinese fluency and cultural understanding surely helped him get beyond the more usual formal interactions that would otherwise have been the rule with his Chinese interlocutors. (Just imagine for example, that moment of first encounter between French and a Chinese farmer in rural Mozambique when French greeted him and then began querying him about his reasons for ending up in the Mozambique hinterland instead of his ancestral hometown in rural Henan Province – all in colloquial Chinese.)

French’s description of the Chinese movement into Africa as a natural outgrowth of Chinese society, forcefully reminded this writer of his own experiences in Southeast Asia years ago. For hundreds of years, Chinese ventured from the same provinces as French’s acquaintances to reach for opportunities beyond the hardscrabble lives they and their families before them had been forced to lead in their homeland for generations.

Out there in Southeast Asia, slowly but surely, the Chinese built up whole networks of traders, wholesalers, importers and exports, and, eventually, manufacturers of all kinds of products. This ranged from the harvesting and exporting of specialty hardwoods (like sandalwood and teak) to the manufacture and sale and distribution of cigarettes; from the wholesale and retail marketing of rice, cooking oils and other basic commodities; and then on to the importation, manufacture and sales of basic kitchen and other household goods – and even onto filmmaking and newspaper production. In the hundreds of years before the Europeans first came to East Asia until World War II fatally disrupted emigration from China, hundreds of thousands of Chinese took a deep breath and deserted their grinding rural poverty to start afresh across a wide swathe of territory from Burma to the Dutch East Indies and then even to many Melanesian and Polynesian islands, and then up through the Philippines.

In some countries such as Thailand, they often intermarried with local families, while in other places; they kept largely apart for cultural, religious and even business reasons. Either way, over time, these communities created deep roots in big cities, small towns and rural villages wherever they lived.

Sometimes, racial violence – tied to politics, economic envy or both – led to pogroms against those old, well-established Chinese communities, redolent of the violent attacks against the Jewish populations of Eastern Europe in the late 19th century. In response to such pressures, the Chinese would retreat back into their communities to hunker down and avoid the worst. As an aside, the writer remembers being offered a chance to buy an entire Chinese temple for the bargain price of $5,000, all carefully disassembled and stored in a grain warehouse in a small town in Central Java. The Chinese community there had taken it down in the wake of the post-1965 riots that followed a failed communist uprising. Its intricately carved teak wood posts and lintels were covered in gold gilt and royal red paint wood slabs and the temple had been disassembled, piece by piece, because they feared a pointed, unfriendly local reaction if they rebuilt a building that had been such a symbol of the prosperity of their community.

And the amazing thing about this vast diaspora of Chinese throughout Southeast Asia and beyond was that it had occurred without any government guidance or direction. Then as now, it had been driven by a desperate desire on the part of those involved to better themselves, even if it meant years of grinding hard work and sacrifice, and their willingness to eat the bitter (chi ku – ??), as the Chinese like to say.

In a similar way, many Chinese made the fraught journey to the Gold Mountain – what the emigrants called California, Alaska and British Columbia, in order to try their hand at gold mining or to provide the services the miners wanted and needed. Chinese contract labour also came to South Africa back at the beginning of the twentieth century as well. Some Chinese, of course, also came North America as contract labourers to build the new railroads, including tackling the most dangerous jobs such as the setting of the explosives needed to tunnel through the mountains.

The point of these Asian and American examples is to set out a historical pattern for Chinese advancement into a continent, regardless of any particular policy patterns by a Chinese government. And these, of course, were just earlier variations of the patterns French has explored as he trekked across the African continent for his book.

Tracking down the exploits of Chinese pioneer entrepreneurs in Africa, he finds farmers, miners, engineers, shop owners, bankers and everything in-between in Tanzania, Zambia, Mozambique, Botswana, South Africa, Namibia, Angola, Ghana, Mali, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea. And he interviews or travels around with these people into their homes and private dining clubs, their homesteads and out there with them in their agricultural projects. Along the way he speaks with African government officials, as well as critics of this “invasion” of Chinese businessmen (and a few women), and even the occasional Chinese diplomat.

French notes that the official Chinese government (through its major state-owned enterprises or lending agencies with their massive loan book) is intent on building a network of relationships and influence through its provision of low or zero interest loans, the construction of stadiums and other public projects. Meanwhile, in the optimistic climate for African growth, individual entrepreneurial Chinese flowing into the various African countries are finding fertile ground for their own activities, most of which are not particularly tied into the official activities in any direct way. Naturally, French finds a whole collection of Chinese construction companies spreading across the continent, bidding and winning contracts for projects financed by those big Chinese investment and lending agencies. But French also finds these smaller companies are competing and winning other construction projects as well, even those financed by the US Government’s overseas investment institutions.

Despite French’s personal respect for Chinese ingenuity and purposefulness, he does not shy away from reporting the not-so-veiled racist feelings about Africans in the mouths and minds of many of his Chinese interlocutors. Too often, in their estimation, French finds these Chinese describing Africans as lazy, dishonest and stupid, and as they marvel at the apparent unwillingness of Africans to work hard for eventual reward. French’s agricultural entrepreneurs repeatedly are astonished, for example, that the incredibly fertile, fallow land across the continent is not being intensively cultivated for produce and profit. And so here is another key element of French’s discovery about this new wave of Chinese in Africa. Rather than exponents of the prevailing political orthodoxy of China, these Chinese in Africa are rugged individualists. They are eager for profit, and, in a weird way, they see themselves as hardy pioneers in a landscape crying out for exploitation. Such people like these Chinese would barely be out of place in the vast saga of the settlement of the American west in the 19th century.

The difference, of course, is that these Chinese frontiersmen and women now exist in a globally interconnected world where, almost wherever they are, they can stay in touch with family and friends back in China via social media and the rest of the Internet’s tools and access – encouraging more immigrants and more business connections. They can watch current Chinese television entertainment and news broadcasts; they can position themselves adroitly with business information and market news; and they can network closely across the continent whenever necessary – almost no matter where they are living and working throughout Africa. This gives them a flexibility and suppleness for responses to business conditions that may well give them a decisive edge in many spheres of business going forward in their endeavours across Africa.

In a laudatory review of French’s book, The Economist tries to weigh the longer-term impact of this Chinese wave. Its review notes, “Far from embracing Chinese values, many Africans have become wary of them. In Guinea, writes Mr French, ‘there was mounting resentment over the way China was seen to be…despoiling the environment, dispossessing powerless landholders or flouting local laws, fuelling corruption, and, most of all, empowering awful governments.’ The dumping of cheap and shoddy goods is another source of complaint, and poor safety standards at work yet another. In Namibia, a local activist says Chinese businessmen often pay their labour a third of the official rate. Illegal fishing, ivory-smuggling and logging by Chinese operators are rife. African worries about such activities and behaviour are gaining ground across the continent.

“Some African leaders, by contrast, plainly like the Chinese approach to government and big business, which puts human rights and transparency totally to one side, while ritually uttering the official mantra of ‘win-win’: Africans and Chinese benefit equally. The presidents of Angola and Zimbabwe are notorious examples, but others abound. Moreover, if Western donors or investors try to lay down conditions on such matters, African leaders have become adept at threatening to ‘go east’. As a massive transactional process, China’s entry into Africa has been a dramatic success, and many of those roads and bridges are useful. But as an ideological and cultural undertaking, Mr French’s masterly account suggests that it is getting nowhere.”

And so a logical question for South Africans is: Where does this leave this nation’s relationship with China, with Chinese big business and investment, and with the individual Chinese businessman? The South African government is clearly hoping Chinese investment capital will flow this way in an ever-increasing, wide, deep river of funds for infrastructure development, even as they hope more direct forms of investment will somehow also begin to soak up some of the country’s appalling levels of unemployment. While the money may come, according to French’s research, many Chinese investments, especially those made by private entrepreneurs who come on their own or gain government contracts, frequently will bring most of their skilled (and even some of their unskilled) labour from China, at least in part based on the poor impression the Chinese apparently have of Africans as employees. And as for any potential wave of Chinese small business entrepreneurs in South Africa, say, at the level of Zambia (where they are now a significant force in the copper industry), it seems unlikely such investors would be delighted to be the willing agents of state-to-state relationships or grand plans, rather than to pursue their own dreams and individualised desires to make new lives, maximise good profits, and build new lives of prosperity for themselves and their families.

Or as French concludes in his own volume, “So far, it can only be said to be top-down in the fuzziest of ways. Indeed, what often impressed me most about the stories of the new Chinese in Africa I met was the almost haphazard quality to the life stories that had landed them in places like Mozambique, Senegal, Namibia, and elsewhere. There was little hint of a grand or even deliberate scheme, but in the end, that’s not so important. As the outraged Ghanaians who seem to have awoken one recent day to discovery that thousands of Chinese newcomers were scrambling illegally to take control of their country’s lucrative gold mining sector, digging up the countryside, despoiling the land, and bribing local chiefs and police officials in the process, might say, it is outcomes that count.”

Given the dynamics described by French, if there is one book South African policy makers – and anyone else interested in the country’s economic future – should read carefully and contemplate thoughtfully in 2015, Howard French’s China’s Second Continent is clearly a top tier contender for that honour. DM

Howard W French’s book, China’s Second Continent – How a million migrants are building a new empire in Africa, is published by Alfred A Knopf, ISBN 978-0-95698-9 (hardback) and ISBN 978-0- 385-35168 (eBook).

Read more:

- Empire of the sums – The mass immigration of Chinese people into Africa is almost entirely driven by money rather than ideology at The Economist

- Book Review: ‘China’s Second Continent’ by Howard W. French at The Wall Street Journal

- The Settlers ‘China’s Second Continent,’ by Howard W. French at The New York Times

- China’s Second Continent: How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa in Foreign Affairs

- ‘China’s Second Continent’ by Howard W. French at the Boston Globe

- China’s Second Continent – How a Million Migrants Are Building a New Empire in Africa – China Turns To Africa For Resources, Jobs And Future Customers at the National Public Radio website

- ‘China’s Second Continent’ tells the fascinating yet alarming story of China’s economic colonisation of Africa at the Christian Science Monitor

Become an Insider

Become an Insider