Maverick Life

Cape Town’s Labia cinema: Go digital or go dark

Independent cinemas are a dying breed in South Africa, casualties of the popularity of DVDs, illegally-downloaded movies and the huge expense of moving to a digital operation. One of the most iconic, Cape Town’s Labia cinema, is launching an attempt to save itself via a crowdfunding campaign. By REBECCA DAVIS.

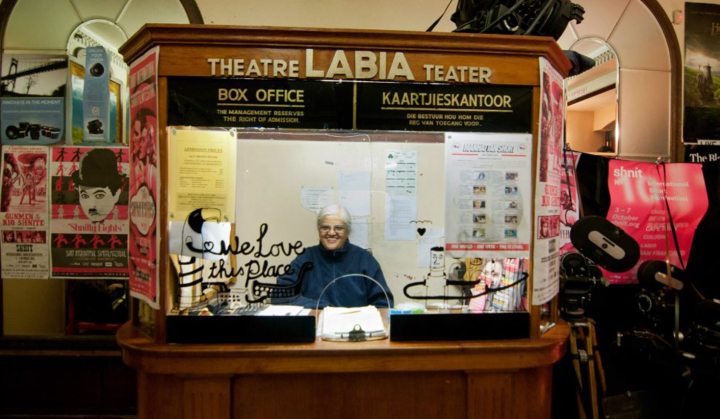

The cliché most often attached to the Labia is that walking into its dark interior is like “stepping into a bygone era”. The experience is certainly nothing like the slick, soulless operations of the major movie chains in this country. Tickets are purchased from an old wooden booth. A bar will serve you a beer or glass of wine to take inside one of the cinema’s four screens. Most of the staff have been clipping tickets and loading up projection reels here for well over two decades.

The seats, it must be said, could be more comfortable; the sound quality more distinct. But the Labia’s patrons overlook these aspects in favour of the slightly dishevelled romance of an establishment which turned 65 this year.

The story goes that the Labia’s premises started life as a ballroom for what was once the Italian embassy next door, bearing the sign of Romulus and Remus, founders of Rome and Benito Mussolini’s hallmark.

“It’s quite a sketchy history,” admits owner Ludi Kraus. “I’m not quite sure whether everything is factual.”

What is beyond doubt, because it is commemorated with a plaque on the wall to this day, is that the building was converted into a theatre by Italian aristocrats the Labia family, and declared open as a place for the performing arts by Princess Labia in May 1949. Count Natale Labia – later granted the title of prince – was a diplomat who was dispatched to South Africa in 1917, and prospered under Mussolini’s regime, though he allegedly tried to talk Mussolini out of invading Abyssinia.

Part of the reason why the family built the Labia Theatre, the Mail & Guardian recorded a few years ago, was out of gratitude to the South African government at not detaining them during World War II.

It is through its Italian roots that the cinema acquired its unusual name. Kraus concedes that it raises eyebrows, but says the name is “too much part of it” to consider changing.

“I don’t know if South Africans catch the connotations that quickly, maybe because they’re less…medically-minded,” Kraus says. “Visitors tend to be far more alert. Some come in here expecting it to be a porn cinema.” He jokes that a friend once suggested naming two screens the ‘Majora’ and ‘Minora’.

Arts journalist Bruno Morphet traced the history of the Labia to commemorate its 60th birthday, writing that the original theatre played host to well-known South African playwrights until the mid 70s. At this point, a film distributor used the premises for a once-off avantgarde film festival, which proved such a success that the Labia developed a new purpose as a dedicated cinema.

Critic Trevor Steele Taylor arranged the weekly film roster, where “you could expect to find anything from Fassbinder to the Marx Brothers being offered on the elaborate hand-printed programmes,” Morphet wrote. As you’d expect from any independent cinema worth its salt during the repressive Apartheid years, there were tussles with the Film and Publications Control Board: Steele Taylor was once removed by police during a screening of The War Is Over, about the Spanish communist revolution.

Kraus took it over in 1989, when the cinema had already seen better days. “It was still quite popular, which was amazing because it was dark, it was dingy, it was dirty,” Kraus recalls.

“You couldn’t hear, you couldn’t see. You came in and there was a broken red couch full of chicken bones. You needed binoculars to see the screen, and if there were subtitles you had to lean into the aisle to read them.”

Kraus was no stranger to the world of the cinema: his father had owned a movie house in Windhoek. He used a crane to bring the movie screen forward and installed better projectors. A rehearsal room upstairs became a second screen, with a third and fourth following.

Kraus says it took him 21 years to make the Labia work, maintaining the cinema’s reputation for screening independent films and hosting small film festivals, while also bringing in some bigger commercial hits to keep the box office ticking over. “The biggest change has been that the audience has got younger in the last three years,” he says. “It’s become a cooler place. When I programme now I have to take that into account.”

Over the past years, the cinema has seen the likes of John Cleese, Matt Damon, Salma Hayek and Colin Farrell pop in for a screening, while Western Cape Premier Helen Zille likes the odd Labia film too.

But it hasn’t all been smooth sailing. Last year the Labia had to close its two separate screens on Cape Town’s Kloof Street after the building’s new owners decided to discontinue them. Kraus says he has given up on any attempt to expand beyond the Orange Street premises. In 2012, the cinema was embroiled in controversy over Kraus’s decision not to screen a pro-Palestinian film because he “didn’t want to get involved in politics”, which led to a call to boycott the cinema.

Today Kraus stands by that decision, though he calls the ensuing fracas the “most unpleasant experience of my life”. He claims that the cinema did not experience a drop in support as a result of it.

But today the Labia faces its biggest challenge to date: the fact that the cinema has to convert its operations to digital. The necessary components for the Labia’s old equipment are no longer available. Film distributors have just stopped providing movies on celluloid. British costume drama Belle, currently showing at the cinema (and starring half-South African Gugu Mbatha-Raw), is the last film Kraus can expect to receive on celluloid. The Labia has to adapt or die – but the costs are astronomical.

“If you want to play, you need the equipment,” Kraus says. “There is no choice. We’re in the penalty shootout phase.”

As with many other ventures these days, the cinema is turning to crowdfunding as a possible solution, using local startup Thundafund. Launched in June last year, the website aims to replicate the success of international models like IndieGoGo and Kickstarter (on which an enterprising young man recently raised over $40,000 to make a potato salad). On these sites, creators pitch a particular project and offer prospective financial backers various incentives to make a donation: an experience related to the project, for instance, or a piece of merchandise derived from the project.

The Labia is aiming to raise a hefty R150,000, to go firstly towards digital projectors and renovations to fit them, but also towards a general rejuvenation of the cinema. The range of rewards that donors will receive in exchange will only be unveiled on Thursday, but Kraus hints that they will include everything from free move tickets to naming rights on the cinema screens.

Kraus is pinning his hopes on the notion that Capetonians will pitch in to ensure that the oldest independent art cinema in the country won’t see lights out just yet. “There’s no place like the Labia,” he says. “It still has the magic of the old world, so hopefully we can combine that with the equipment of the new.” DM

The Labia’s ‘Go Digital Or Go Dark’ Thundafund campaign kicks off on Thursday on https://www.thundafund.com/thelabia

Read more:

- Grand old lady of the Gardens, on M&G

Photo of Labia by Mallix.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider