South Africa

Commissions, task teams and the state of SA

It is not an everyday occurrence for a person with the title “President” prefixed to their name to appear before a court or government inquiry. Nelson Mandela has so far been the only sitting head of state to testify in court. On Thursday, former President Thabo Mbeki appeared before the judicial commission of inquiry investigating the arms deal. In years to come, perhaps other incumbents might face a similar fate. The plethora of commissions and investigations goes to the heart of leadership and accountability in South Africa. And they do not reflect well on the state. By RANJENI MUNUSAMY.

In March 1998, then President Nelson Mandela appeared before the Pretoria High Court in a case instigated by the rugby boss at the time Dr Louis Luyt. It was one of the few times the world saw Mandela publicly furious.

Before taking the stand, Mandela said his blood boiled at having to be dragged to court by Luyt to explain his decision to set up a commission to investigate racism, corruption and nepotism in rugby. He also said he had grave reservations about the unprecedented order for him to appear in court because it might open floodgates by which all presidential decisions might be challenged and government undermined, it was reported at the time.

Luyt argued that the South African Rugby Football Union (Sarfu, now just Saru) was a private association and that government should not interfere in its affairs. Mandela said Sarfu could not be left to regulate itself when internal democracy seemed lacking. He tore into Luyt in his testimony: “The feeling is that Louis is a pitiless dictator… No one can stand up to him.”

“I would never have imagined that Louis would be so insensitive, ungrateful and disrespectful to say when I gave my affidavit I was lying,” Mandela told the court, fuming.

Sixteen years later, Mandela’s successor, Thabo Mbeki, appeared as a witness before the Seriti Commission investigating South Africa’s multibillion rand arms acquisition, and he was similarly furious. Mbeki’s anger was directed at Advocate Paul Hoffman who was cross-examining him on his involvement in the arms purchase. Hoffman is representing anti-arms deal campaigner Terry Crawford-Browne at the commission.

Hoffman appeared ill-prepared and his questions were based on conjecture and rumours churning around the arms deal since 1999. Throughout his political career, it has been difficult to get Mbeki to make admissions, concessions or backtrack on his positions, even on highly controversial issues such as his position on HIV/Aids. Considering that there has been no firm evidence of corruption on Mbeki’s part relating to the arms deal, Hoffman had to have done his homework and mapped out where he wanted to go with his line of questioning.

He did not, leading to a day of constant legal head butting and Mbeki venting his anger at Hoffman’s condescending attitude and offensive remarks. After becoming emotional several times during the cross-examination, Hoffman eventually had a meltdown, apologising to Mbeki and weeping openly about a personal tragedy.

The appearance of Mbeki at the inquiry was highly anticipated and Crawford-Browne had campaigned for well over a decade for the opportunity to question him about the arms deal. It eventually came to naught as Mbeki was able to stonewall the questions by saying he did not know the answers or could not recall the events. In fact, nothing that has been led before the commission so far has produced the smoking gun showing corruption in acquisition.

Part of the problem is that the commission of inquiry is taking place 16 years after the arms were purchased, and it is therefore understandable that much of the recollection of what happened then would have receded. When allegations of impropriety arose after the acquisition, there was fierce opposition and bullying from government to proper investigations into the matter.

But Hoffman could still have done more. One issue Hoffman could have pushed Mbeki on, for example, was a letter sent to the chairman of the Standing Committee on Public Accounts, Gavin Woods, slamming the committee’s investigation into the arms deal. The letter was signed by then Deputy President Jacob Zuma but it later emerged that it was in fact written by Mbeki. If there was nothing untoward in the deal, there should not have been such high-level attempts to stop investigations into it. Parliament, in fact, would have been the most appropriate forum to probe the matter.

And there began the problem with government’s attitude in dealing with allegations against it. In many instances, the cover-up is more scandalous than the original allegations. This has been evidenced over the past few years in how the state dealt with the landing of the plane carrying Gupta wedding guests at Waterkloof Air Force Base and the security upgrades at Zuma’s private residence at Nkandla.

The Waterkloof incident was investigated by a government task team and the fallout contained. The Gupta family and the political connections they manipulated to allow the plane to land and for their guests to get preferential treatment from customs and police escorts to Sun City were not held to account. Although the incident amounted to a serious breach of a military facility, the matter was swept under the carpet.

Similarly with the Nkandla matter, a government task team was appointed to investigate the matter and tried to shift responsibility for the exorbitant expenditure to low-level officials and contractors. There was a deliberate effort to shield Zuma and members of his Cabinet from being held accountable. When Public Protector Thuli Madonsela was investigating the matter, she was bullied by the security cluster ministers and was not given the co-operation she required from the presidency and other state departments.

The matter still lingers now with presidential spokesman Mac Maharaj announcing on Thursday that Zuma required more time to submit a response to Madonsela’s report to Parliament.

Perhaps the most shocking example of government refusing to take responsibility for their actions has been in the Marikana Commission of Inquiry. The commission has dragged on for close to two years with a constant denial of accountability from the South African Police Service for shooting dead civilians. The behaviour of people like National Police Commissioner Riah Phiyega before the Farlam Commission showed disrespect for human life.

Commissions and task teams have over the years become means for the state to buy time, manipulate outcomes and dodge responsibility. They have not been platforms which allow proper scrutiny over how the state is managed and which can provide the South African public with a full picture in instances of wrongdoing.

Parliament should be the place where the executive and government departments are held to account, but the ANC has constantly used its majority to protect the president and his ministers, and prevent proper probity into the state’s affairs.

This has placed a heavy reliance in recent years on the Office of the Public Protector as the only credible institution that can properly investigate people in the state accused of wrongdoing. Madonsela’s respect for the public’s right to know and refusal to bow to political pressure has made her office the only reliable port of call when allegations of impropriety arise.

Yet, even this week, the Ministry of Justice has claimed that she is overstepping her mandate and taking on investigations that other institutions could deal with. They appear oblivious to the fact that because of the way the state conducts itself and strong-arms those investigating it, the public does not trust other investigations, particularly internal government probes.

South Africa is sailing close to the rule of law being undermined with the Constitution and Chapter Nine institutions being disrespected. Political accountability is also dangerously low with signs of contempt for the judiciary and Parliament.

On the face of it, it appears remarkable that a former president and former minister of police appeared this week before separate commissions of inquiry investigating the two biggest scandals of post-democracy South Africa. The reality though is that neither of these appearances will result in any significant outcomes.

While the commissions may in theory appear to work on strengthening the democracy and accountability in South Africa, in reality, used in conjunction with an unlimited legal budget, they are but a political tool to protect those in power. Neither human life nor the public purse can compete with the preservation of power. DM

Read more

-

Tears and missed opportunities as Mbeki coasts through arms commission on Daily Maverick

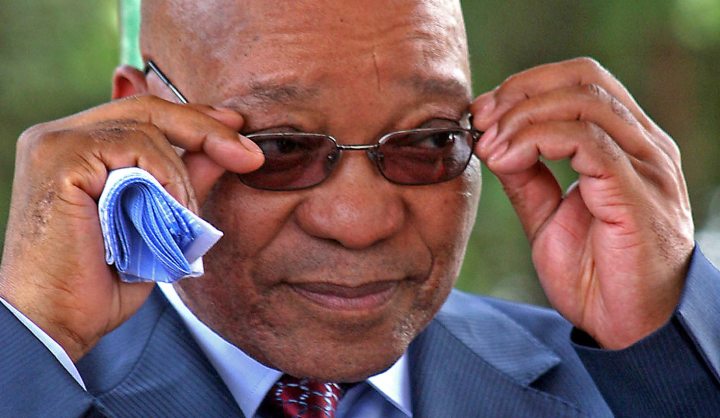

Photo: President Jacob Zuma. REUTERS/Mackson Wasamunu.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider