Maverick Life

Fugard’s daughter: Lara Foot finds a universe in a small story

It was playwright Athol Fugard who, during the Apartheid years, was able to distill a sort of literary, existential and geographical transcendence from the smallest stories. Two homeless people in “Boesman and Lena”, two fractured siblings in “Hello and Goodbye”. Working in the post-Apartheid landscape, playwright and director Lara Foot echoes many of Fugard’s themes of hope and redemption. Her latest play, “Fishers of Hope Tawaret”, continues this tradition, but this time takes the narrative beyond our borders. By MARIANNE THAMM.

In his introduction to Lara Foot’s first solo play Tshepang – originally performed in Amsterdam in June 2003 and written as part of Foot’s MA thesis at Wits – clinical psychologist Tony Hamburger observes that Foot’s work “tracks a direct artistic bloodline that starts with Athol Fugard”.

“It continues a direction initiated in the late 1950s by Fugard and his colleagues John Kani, Winston Ntshona and Barney Simon. This school could be identified in many ways as ‘protest theatre’, ‘political theatre’, ‘anti-Apartheid theatre’. And although those appellations are not inaccurate, they exclude a universality and timelessness. These playwrights are concerned with themes that go well beyond the specifics of a particular time and political era and a uniquely South African racial situation,” wrote Hamburger.

“Tshepang”, penned in the aftermath of the rape of a nine-month-old infant, Baby Tshepang (Hope) in Louisvaleweg in Northern Cape, was an attempt by Foot to understand the history and context as well as the internal and external worlds of the protagonists and which led to the unfathomably horrific violation of a child.

Both Fugard and Foot seek a kind of clarity and meaning in the darker, difficult spaces of human existence and in so doing, remarks Hamburger, attempt to find purpose or possibility in situations where there appears to be none. This is not theatre that merely entertains. This is theatre commands us to engage – with the characters and with the human condition and its full range of experiences, limitations and potential.

Foot’s more recent solo work, including Hear and Now and Reach (later restaged Solomon and Marion), were two-handers with characters weighed down and emotionally marooned but who ultimately find ways of connecting and locating a space for acceptance and understanding.

Foot’s newest play, Fishers of Hope Tawaret, is the first she has set outside of the mental and physical landscape of South Africa. To research the play, Foot journeyed to a small fishing village near Kisumu in Kenya.

The work, she says, was inspired by the Austrian-French-Belgian co-production, Darwin’s Nightmare, about the disastrous environmental and social consequences of the introduction of a species of fish, the Nile Perch into Lake Victoria in Tanzania. The Nile Perch caused the ultimate demise of indigenous fish species and endangered the livelihoods of locals who were left to fend for themselves. The Nile Perch is caught and processed to be exported back to Europe, carried there in the in same aircraft used to transport arms and weapons to Africa.

Experiencing a country and its citizens 50 years after independence has enabled Foot to engage with the material unencumbered by a recent “colonial” or “struggle” history, ghosts that so often still haunt work set in South Africa. This is a story that ripples out way beyond the shores of this lake and this village.

And while it does this, Fishers of Hope – Tawaret is, to all intents and purposes, an apparently simple story of one household. While it may literally and metaphorically be a million miles from the modern world, as we know it, this “home” is well and truly part of a “global village”.

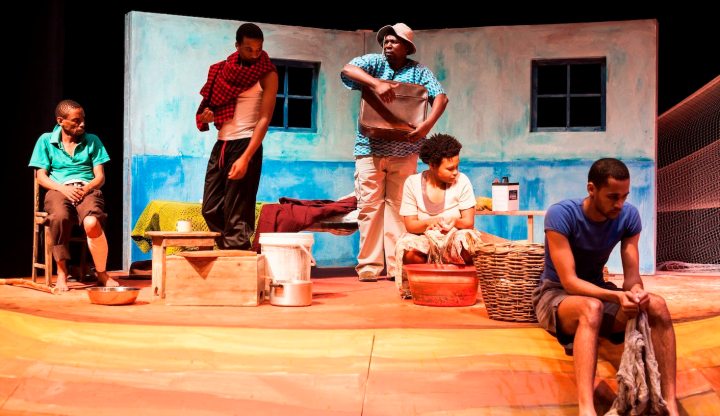

And so our escort to this particular village is the avuncular and mischievous Njawu (played by the charismatic Mncedisi Shabangu), a tour guide. He offers his American and European tourists the face of Africa he knows they want to see. He answers their silly questions with self-possessed charm; he endures their ill-informed opinions about his country and poverty with controlled good humour. It is Njawu who darts in and out of the narrative, breaking the fourth wall to banter with the audience (the tourists) before disappearing into and connecting us with the lives of those left to survive in a dilapidated and sparsely furnished home perched on the shores of a lake.

A proud, determined and hard-working fisherman, John (played by wiry Phillip Tipo Tindisa) is badly injured after an attack by a hippopotamus. His injuries prevent him from being able to feed his family, which includes his resourceful wife, Ruth (played by Lesedi Job, who delivers a powerfully understated performance) and their ‘adopted’ son Peter (played with great empathy by the athletic Shaun Oelf). Peter has lost the ability to speak and here Foot expertly employs physical theatre to convey the young man’s anguish.

Ruth’s disaffected brother, Niara – played by Philip Dikotla with the kind of fiery intensity of a young man who has been betrayed by politicians – hitches a ride with Njawu to the village. His arrival upsets the fragile equilibrium just as the alien fish species has upset the balance of the lake. His restless need to be mobile, to keep moving to somehow escape the stasis and decay he feels all around him unleashes the undercurrents that have somehow paralysed the family, trapping them in a never-ending struggle to survive, materially, emotionally and spiritually.

Within these small lives and this small story a universe is contained. While never obvious or mawkish, Foot’s lyrical text deals with pride, disempowerment, change, power, love and death. She has realised a finely tuned set of characters that are brought to life with astonishing and delicate authenticity by an accomplished cast – so much so that this reviewer was moved to hug in the foyer one of actors whose character Foot kills off in the play.

Fishers of Hope Tawaret is a multi-dimensional sensorial experience with subtle videography by Nina Swart, and a haunting soundscape by The Carnell Collective beautifully performed by Nceba Gongxeka. Grant van Ster’s choreography is as fluid as the water of the lake. Lighting by Benever Arendse and Patrick Curtis’ set design and scenic art recreates and reflects the subtle tensions that unfold.

Like Fugard, Foot is inevitably drawn to the notion of hope and love. Concluding his thoughts about Tshepang, Hamburger writes, “Perhaps then Tshepang is a play about love. Love as a relationship. Love as comfort in our human journey, which, for so many people, is one through hell, but which becomes tolerable and hopeful with another’s empathy.”

And this is exactly what Foot has achieved with this beautiful, simple tale. Fishers Of Hope Tawaret is on at the Baxter Flipside until 2 August. DM

Photo: Phillip Tipo Tindisa as John, Phillip Dikota as Niara, Mncedisi Shabangu as Njawu, Lesedi Job as Ruth and Shaun Oelf as Peter in a scene from “Fishers of Hope Tawaret” (Picture The Baxter Theatre)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider