Africa

In the Name of the People: A book review

Lara Pawson has written an African non-fiction classic on a brutal day in Angola’s history. Her book isn’t an answer, it is the Answer. By RICHARD POPLAK.

See, this is how it’s done. What a book, what a book! Let me calm down and explain.

As far as African countries go, Angola is hardly unwritten. Its first president, Agostinho Neto, was a famous poet; his political negative, Nito Alves, was a poet too. Over the years, the country has flaunted a brigade of immigrant writers like José Luandino Vieira, a handful of unbelievably courageous opposition figures like Rafael Marques, and a good half dozen superb expat reporters like Louise Redvers. And Angola has spawned its hacks, it shills, its mouthpieces. Nonetheless, the country demands great sentences; its Latin fetidness begs for big imagery. But if Angola has made it into the book section of your local rag of late, it’s due to Paul Theroux’s The Last Train to Zona Verde, the Africa travel narrative that may have ended African travel narratives, and not just because it concerns a botched African travel narrative.

Theroux’s book is about the Great Travel Writer’s final trip through his adored Africa, a continent he fell in love with when he worked as a Peace Corps volunteer in Malawi in the 1960s. It is Theroux’s intention to travel up the western flank of the continent, all the way from the Cape to Nigeria, or perhaps further north. A quick squizz at a map allows that this is the opposite end of Africa from Malawi, and a glance at the calendar tells us that we have flashed forward some decades in time since the 60s. But whatever Theroux (as seasoned a traveller as any) is expecting from his journey, it runs aground in Angola. Those three humid syllables bring him nothing but a bad headache and the shits; it’s where the Old Africa properly gives way to the New, where “the misery of Africa, the awful, poisoned, populous Africa; the Africa of cheated, despised, unaccommodated people, of seemingly unfixable blight: so hideous, really, it is unrecognisable as Africa at all” comes gloriously into view.

One starts to notice something about Theroux’s Africa early on in his peregrinations: he is the only one talking. There are no other voices. He asks maybe a handful of questions, yet arrives at dozens of inflexible positions. The further he goes, the deeper he travels, the more he unintentionally parodies Conrad: “I became conscious of entering a zone of irrationality,” he notes. “Going deeper into Luanda meant travelling into madness.” Which is not properly true, because Luanda can be read—is read—by those who know it well, to say nothing of those who express the industrial-grade curiosity investigative journalism demands. That the context can induce madness doesn’t make the context any less important; it is the travel writer’s job to go there, if nowhere else.

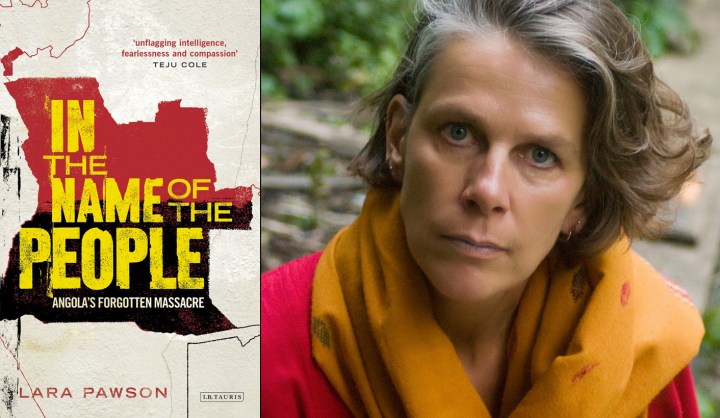

We arrive, then, at Lara Pawson’s In the Name of the People: Angola’s Forgotten Massacre, which is probably not designed as an antidote to Theroux, but serves as one nonetheless. In every way that the former book is lacking, this one is a towering success. Stuffed with death, it nonetheless brims with life, with a curiosity that is both moral and unwavering, bearing the courage to ask: if this is indeed a mess—and boy, is it, why might that be? In the asking, Pawson has written an African non-fiction classic, which is the toughest kind. The book serves not as an answer, but the Answer: if we hope to understand our present circumstances, then we must go in search of the past, and what we fail to find must somehow be worked into our stories regardless.

In many respects, the conceptual framework of Pawson’s book mirrors Theroux’s: a Briton who worked for many years in Lusophone Africa as a BBC correspondent, she remains obsessed with her African memories and hopes to return one day to deal with unfinished business. In Pawson’s case, the catalyst is a date missing from Angola’s official calendar: vinte e sete de maio, or 27 May, 1977.

This day is whispered under the breath in code—to so much as mention it is taboo, a break with the conventions of Angola’s cultura do medo, or culture of fear. It may seem somewhat counterintuitive that after four decades of brutal civil war Angola has an atrocity that remains unspeakable, but vinte e sete is of a different order. This is the day that Neto’s People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola, or MPLA, turned on itself. This was the liberation’s movement’s murder-suicide, and it remains the most painful date in the country’s incredibly painful history.

Very few people have waded through vinte e sete’s thicket of corpses. For one thing, average Angolans are terrified of the ruling MPLA, and that’s because Jose Eduardo dos Santos’s MPLA has made sure they understand the consequences of dissent. For another, many of the expat journos covering the endless civil war—Pawson among them—believed that the party in its earliest days represented a sort of Marxist, or at least leftist, paragon. In many respects, the book details the absurdity of such a notion and we witness the writer fall madly out of love with the last of her shibboleths. “I feel torn between the search for truth and my political beliefs, which I’m beginning to think, in itself, is rather a luxury,” she notes drily.

Ideology, we learn over the course of In the Name of the People, has almost always served as an Angolan cudgel. (The book’s title functions as the bitterest of ironies). A procedural that swings from London to Lisbon to Luanda, and back to London, the book tries to track some hard information about the thousands—or was it tens of thousands?—of murders that took place on vinte e sete. She meets still-shattered widows, broken spooks, soaked journos, vainglorious propagandists, fading politicos—the cast of Graham Greene’s entire oeuvre. What she finds is what is for the most part already known: there was factionalist split within the MPLA, driven largely by the charismatic Marxist/Maoist Nito Alves. The netistas squared off against nitistas, and when an attenuated coup-type thing was initiated on 26 May, several Neto supporters were killed in Luanda’s Sambizanga neighbourhood, and the usual game of independence-era factionalist slaughter was on.

Except there is no “usual game”, because the devil is in the details. In Angola’s case, there was its fabulously complex racial politics: “the negro, born of black parents; the cafuso, born of a black and a mestiço parent; the mestiço, born of one black and one white parent; the cabrito, which translates as ‘goat’, born of a mestiço and a white parent; and the branco, born of two white parents.” Where Neto was backed by a strong white Angolan and mestiço faction, “famously,” notes Pawson, “Alves said that there would only be true equality in Angola when white people were seen sweeping the streets alongside blacks.” Angola’s racism is like a python with spina bifida, a creature in constant agony that keeps opening up on itself. What species of racism did Neto, who was married to a white woman, constantly rail against: the racism of the white and mestiço elites against the black masses; or black racism against white and mixed race elites?

Stir in the Americans, the Soviets, the Cubans, the Chinese, and a civil war that still had almost a quarter of a century’s fuel left in the tank, and Pawson’s investigations continually slam into walls. “Why,” Pawson asks herself, “am I so interested in such a dark but apparently minor moment in Angola’s contemporary history? What am I trying to prove? I’m still not sure I know.”

In many respects, that is the driving question of the book. Pawson exquisitely draws a Luanda that is constantly being erased and reformulated. Bound up in the architecture of the vinte e sete are the many thousands of brutal days that came before it:

My desire to verify the past by revisiting the places I’ve held in my head all these years isn’t coping well with its dismantling. Wherever I walk, bulldozers seem to be burrowing into the broken land, turning ancient sites into crumbling craters emptied of history. I ponder the connection between memory and landscape. Once the Baixa has been remodelled, will I discover that my memories have been remodelled too? Perhaps this is precisely that: an attempt by the elite to persuade people to forget the past. Or am I guilty of romanticising the architecture of a European power because of my own cultural upbringing? Why should Angolans maintain the bricks and mortar of colonialism? Maybe it’s more appropriate to demolish every last particle of that brutal past.

History, Pawson finds, is a quilt, a patch-job, a group OS hack. In the gaps where there are no convenient truths, the dead linger, though no more dead than the rest of us are alive. The only thing Pawson seems to be sure of is that the vinte e sete de maio remains an open grave into which Angola dumped its future. The trauma of all that happened on that day, the wounds that continue to bedevil both the victims and the perpetrators, are the country’s real story. No one has healed, and no one will. In this vicious, brief, and blinding act of civil conflict, Angola came undone.

And yet, in her epilogue, Pawson details the first stirrings of an Angolan opposition movement, a number of the participants of which go by the nom de guerre Nito Alves. She informs us that small protests occurred on 27 May 2013, commemorating the “massacre” that functions as the country’s ever-metastasising social tumour. They are the courageous few who at great personal risk continue to note, as Chinua Achebe did in his poem Agostinho Neto, “The sinister grin of Africa’s idiot-kings/Who oversee in obscene palaces of gold/The butchery of their own people.”

So this is how it’s done. A methodical plod through a blood-soaked day that reaches far back into Angolan history; a story of an investigation into a plot that ends up revealing the soul of a people. Theroux, the grump, didn’t need context—he required only a mise en scene for his own histrionic disillusionment. Pawson needed murmurs, voices, cries from the dark. She has built a bridge over an empty day in history. Africans will need many such bridges if we are to make it to the other side. DM

Photo: Lara Pawson and the cover of her new book In the Name of the People: Angola’s Forgotten Massacre.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider