South Africa

The Cape’s youth gangs: Bigger, deeper, more dangerous

Gangsterism in the Western Cape is rife. In 2013, 12% of the 2,580 murders in the province were gang-related (2nd behind arguments turned violent), according to the South African Police Service. This is an 86% increase from 2012. In addition, children as young as 14 are being arrested on gang-related murder charges. If the social and environmental factors that nurture gangsterism are left unaddressed, there will be small hope for the children and young adults gripped by gangs in the Western Cape. By SHAUN SWINGLER.

The Apartheid relocation of coloured and black people from the Cape Town inner city to the Cape Flats and surrounding townships had a powerful effect on those relocated. The social dislocation nurtured conditions for the burgeoning street gangs of the early 1980s to thrive, according to criminologist Don Pinnock, in his 1997 book Gangs, Rituals, & Rites of Passage.

Suburbs on the Cape Flats such as Manenberg, Elsies River and Parkwood have deeply entrenched, decades-old gang structures. And there are now fledgling gangs forming in the townships of Khayelitsha and Nyanga.

Just how to deal with this problem has become a much-debated and highly politicised subject, with Western Cape premier Helen Zille recently calling for the SANDF to be deployed to the Cape Flats to do the work the police have seemingly failed to do.

Gangs were most often formed by children seeking physical protection from threats in their communities, according to Major General Jeremy Vearey, Provincial Commander of Operation Combat – the specialised SAPS Western Cape anti-gang strategy unit.

However, Vearey argues that these youth groupings now get “perverted in a gang environment – with the money, the drugs, the girls,” and the children become easy targets for recruiting when so-called Cape Flats ‘super gangs’ such as the Americans and the HLs (Hard Livings) require hitmen for their drug and turf wars.

“It’s very different to how it used to be,” says Rodney Amanshure, ex-leader of the Naughty Boys gang in Parkwood.

“We used to get together in these smalls groups when we were 10, 12 years old. Then one clique would start fighting with another – it was a slow thing. But now it happens too fast. These kids are rushing.”

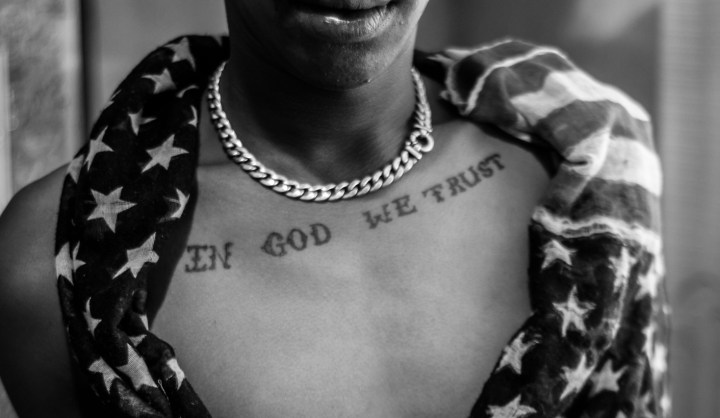

Parkwood is now run by the Americans, where children as young as twelve have been seen by the Daily Maverick with the Americans’ gang motto ‘In God We Trust’ tattooed across their chests.

Amanshure recruited many children because he says they were eager to prove themselves and often got off lightly when caught. “They want to show me who they are because they mos now want to go up in the ranks.”

Youth gangs on the Cape Flats are well established; however, there are burgeoning youth “proto-gangs” growing in size in Khayelitsha and Nyanga as well. This is according to Dr Kelly Gillespie, an anthropologist at the University of the Witswatersrand, who has engaged in research into criminal justice in the Western Cape for the past twelve years and has more recently researched the growing youth gangs in Khayelitsha. She describes these proto-gangs as groups which are not yet fully formed gangs, but which exhibit many of the characteristics of formal gang structures.

Wars between proto-gangs such as the Vuras and Vatos have been spreading fear among Khayelitsha residents in recent years.

“What I found… is that a lot of these groups are forming less through safety and more from issues of style and commodity,” she says. “One day a group of kids started wearing their caps in a particular way and then that style caught on. The style and commodity between groups slowly turn into competition and then hostility.”

If left unchecked, Gillespie warns that these proto-gangs will become more sophisticated. “Most gangs in Cape Town have started in similar circumstances with very similar dynamics as the ones that are happening in Khayelitsha.

“There is already an incredibly sophisticated gang and drug economy in this city – there’s no reason why Khayelitsha can’t be a part of that,” she says. “It’s actually amazing that it’s taken so long.”

There are 12 recognised street gangs and three prison gangs in the Western Cape, according to the SAPS; however, there are tens of smaller gangs, says Vearey. An estimate from the early nineties lists the total number of gangs in Cape Town at 130, and gangsters at 100,000, according to Andre Standing in a 2005 Institute of Security Studies policy discussion paper.

Vearey argues that a combination of drugs, lack of safe common spaces, and the intergenerational transmission of violence lead to the creation of teen gangsters. He also argues that children often look to emulate their fathers or uncles when joining gangs.

Amanshure left his gang life behind for fear of his son following in his footsteps. “I’ve used my experience to tell my son who’s in matric now that this life is not going to pay,” says Amanshure.

Others are not as fortunate.

“On the Cape Flats, your first experience with violence is not on the streets, it’s in the house,” says Vearey. “By the time that you’re 14, 15, 16, you’ve seen a hell of a lot more than what you’ve seen on the street when it comes to gender-based violence, when it comes to fighting.”

In 2003, Western Cape police’s specialised gang unit was disbanded by then-police commissioner Jackie Selebi.

Subsequent rising levels of gang-related violence forced the creation in 2010 of a focused cross-departmental anti-gang strategy headed by Vearey, known as Operation Combat. Operation Combat’s objective is to take down high-ranking gangsters in the province and prosecute them under the Prevention of Organised Crime Act (Poca).

Poca was put in place to target organised crime and gang activity, specifically money laundering and racketeering, and put in concrete terms the strict definitions of gang activity, to better enable successful convictions of gang members.

Operation Combat and Poca have already seen success with the high-profile convictions of 16 high-ranking members of the Atlantis Fancy Boys and six high-ranking 28s from Valhalla Park and Bishop Lavis – convictions made possible by two years of intelligence gathering by the SAPS and careful work by the NPA, according to Vearey.

Poca gang cases will be in court throughout 2014, including the first-ever prosecution of imprisoned gangsters – an attempt to dent the firmly established gang structures in Western Cape prisons.

In Operation Combat, Vearey believes that community mobilisation is crucial to success.

“Gangs make business on areas that we call the commons. The commons are your schools; your parks. Our job in terms of community mobilisation is to get the community to take back [the commons]. We direct our neighbourhood watch, we build street committees.”

He also argues that the success of the strategy can only be fully realised if there is cross-departmental co-operation between the SAPS and the departments of development, education and community safety. He says that this collaboration has been slow to be realised at present, but with concerted effort, greater synchronicity between departments can be achieved, resulting in greater impact in the affected communities.

The developmental approach is intended to be a more sustainable solution to the gang problem. It avoids what Vearey calls the “fire-fighting approach”: alleviating the symptoms rather than addressing the cause.

This is essential because merely throwing young offenders in prison is ineffective, argues Dr Gillespie.

“We really want to keep kids out of prison,” she says. “I’ve seen so many young men get arrested when they’re early on in their engagement with formal gang structures and they go to prison and there they become deeply entrenched in those gangs.”

The Child Justice Act of 2008 attempts to address this problem by limiting a child’s exposure to the adverse effects of the formal justice system by prioritising diversion programmes for juvenile offenders.

One such diversion programme is the Ottery Youth Care Centre. The centre provides a CAPS curriculum and vocational training to 40 boys between the ages of 10-17 years. Youths who have received court orders may enrol.

Ridwan is a student at the school. At the age of seven, he joined a central Cape Town-based gang known as the Junior Mafia Syndicate.

“You get chosen. They see your talent and if they see you’re good looking, you’re clever, they’ll bring you in,” he says. “If you’re disadvantaged in life, the Mafias will come to you and help you. They’ll give you everything you want just for that short period of time.”

Now 17, Ridwan has spent most of his childhood moving between juvenile detention facilities. He was originally sent to a reformatory for robbing his school at the age of nine, but was later transferred for offences ranging from drug dealing to stabbing a warder. After his behaviour improved, he was moved to the Ottery Youth Care Centre.

He speaks with ambivalence about his gang life. He is “prepared to die” for his gang “brothers” but realises that, after a recent attempt on his life by a rival gang member, this lifestyle will ultimately only bring him harm.

“Mostly the thing is I don’t want any more to be a part of this because I can see it won’t benefit me in the long run. One day I will have children, my children will be influenced by these people and maybe my child will be in a rival gang, then one of my friends’ children will shoot him.”

Ridwan is head prefect of his hostel and is making good progress, according to his teachers.

Other initiatives are also in place to address the problem.

The Department of Community Safety is investing in job creation and youth enrichment in high-risk gang areas. According to MEC of Community Safety, Dan Plato, in a letter dated 7 April to the Cape Argus, the Youth Work Programme run by the department has seen a further 1,400 job opportunities created for at-risk youths, and almost R2.5m provided in financial assistance to religious organisations working to address youth crime in high-risk areas of Cape Town.

Even with initiatives such as these, many members of gang-ridden areas who spoke to Daily Maverick have argued that not enough is being done by government departments and the police.

One such community member is Stephanie, 24, who became wrapped up in the gang lifestyle when she began dating an Americans gangster in her early teens. She quickly learnt it would come at a price.

“They [rival gang members] don’t just hurt the gangsters that they’re trying to get to,” she says, “They go for the girlfriends or the other people that the gangsters love.

“I have a lot of regrets. It’s something you can’t get out of easily,” she says. “When you know too much there’s basically no way out.”

“For any teenage girl to get involved with a gangster, they must consider this,” says Rashad Allen, an ex-26 gangster and Parkwood community member. “The gangs worry that maybe the girls will get involved with the enemy and they will give them all their secrets.”

And if she does that, “they’ll rape and kill her,” says Rodney Amanshure. “They must do that.”

The problems facing the gang-plagued areas of Cape Town are many and nuanced. But with gangsterism so deeply entrenched in the lives of so many children and young adults on the Cape Flats, only a solution which forces the co-operation of all relevant departments and institutions is likely to succeed in making a difference to these children’s lives. DM

Photo: A teenage gangster with the Americans’ gang motto tattooed across his chest. Parkwood, Cape Town. (Shaun Swingler)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider