South Africa

Analysis: Politics without politics

Politics has lost the culture of debate – a vibrance that was, sadly, far more prevalent in the days of struggle. By RAYMOND SUTTNER.

What is depicted as politics today sees the predominant areas of contestation being in relation to positions of power and wealth. Consequently, when analysts speak of factions or someone likely to be appointed to a particular position, discussion is devoid of political content. It relates to who is rising or falling, as part of ongoing efforts to secure positions.

There was a time when those who were close to particular leaders represented specific visions of the transition, emphasising one or other strategy in the 1980s and in the early 1990s, advancing or resisting certain concessions in negotiations. These positions were debated. While Joe Slovo and Thabo Mbeki had common positions over a government of national unity, many others questioned the merits and demerits, sometimes with considerable passion.

The debate over the ‘sunset clauses’ was within the context of unlocking possibilities for democracy and transformation. When people advanced one or another position, they did so with the understanding that disagreement related to the best strategies and tactics required to achieve broad emancipatory goals.

What is unfolding in the ANC today has a different implication for the character and future of democracy in South Africa, from what many of us envisaged in the 1990s. The ANC played a key role in defeating Apartheid and inaugurating democracy, where citizens joined together in turning rightlessness of the majority into rights for all. This has been prescribed in a constitution enshrining political freedom but also placing obligations on government to secure the social and economic wellbeing of those marginalised under Apartheid.

Uneven though it may have been, the ANC was part of ongoing debates inside and outside the country, advancing emancipatory ideas, and the quest for a country where creativity would thrive.

In the early days after the organisation’s unbanning, I resisted the ‘normalisation’ of the ANC, meaning its transformation into a conventional political party. This was favoured by many scholars as well as foreign advisers. I understood this to mean that the vibrancy I associated with the struggle, (possibly with elements of innocence and romanticism), the battle of ideas in the days of the UDF and in many of the MK camps and units of the ANC in various countries, would be lost. I feared the ANC would follow many countries where political parties, previously rooted in popular struggles, were reduced to voting machines, losing their earlier vitality. That is why, perhaps unrealistically, I clung onto the notion of the ANC being a liberation movement. I understood this to signify ongoing interaction between the membership and the organisation, whether in Parliament or in carrying out activities within its own structures.

What has happened since 1990 is not merely that the ANC has become similar to conventional political parties, and focuses on winning elections and governing. But the ANC, like some other parties, has followed a ‘normalising’ route that also represents a corrupt version of modern politics.

Susan Booysen writes in the Sunday Independent (6 April 2014) of a “precarious game of institutional warfare that the Zuma-ANC plays around Nkandla. The game undercuts institutions that are prized cogs in the wheel of South African democracy. All is fair in this game to preserve the power of the president.

“It matters little to the main perpetrators that their tricks of institutional manipulation of Parliament and the office of the public protector are transparent….The Zumaists are literally executing a scorched earth strategy on public institutions to help preserve their ringside seats to the trough.”

Related to widespread public anger, the predominant focus of opposition at the moment relates to ongoing scandals, in particular Nkandla and also the need to resist legislation that represents a return to patterns of the Apartheid era, notably the TCB, The Secrecy Bill and deceptive legislation around land redistribution.

Looking back and trying to understand how we have arrived where we are, one recalls that the ANC had been seen as a ‘government-in-waiting. It may have been naïve to understand this purely in relation to governance. It may be that even in the early days of the transition some were positioning themselves to hold powerful and/or lucrative positions.

But ‘visible politics’ then was about ideas and these were debated in various places, before 1990 and for some years afterwards. Sometimes debate was less vibrant than at other moments, but there were definitely vigorous discussions over how to achieve goals and the goals themselves were often contested. That is now being lost.

Any attempt to recover democracy must also retrieve the culture of debate. There was a time when many of us hungered to read and debate what was then illegal and poured over dog-eared copies of illegal publications. Now we can read what we need. It is our duty to restore and build debate on the burning issues of our time. Unless we reclaim the right to debate, to bring politics back into politics, to debate emancipatory principles and ethics, we are likely to be condemned to endure continued cycles of the current morass. DM

Professor Raymond Suttner, attached to Rhodes University and UNISA, is an analyst and professional public speaker on current political and historical questions and questions of leadership. He writes a regular column and is interviewed weekly on Creamer Media’s polity.org.za. Suttner is a former political prisoner and was in the leadership of the ANC-led alliance in the 1990s. He blogs at raymondsuttner.com.

This article first appeared on Creamer Media’s www.polity.org.za

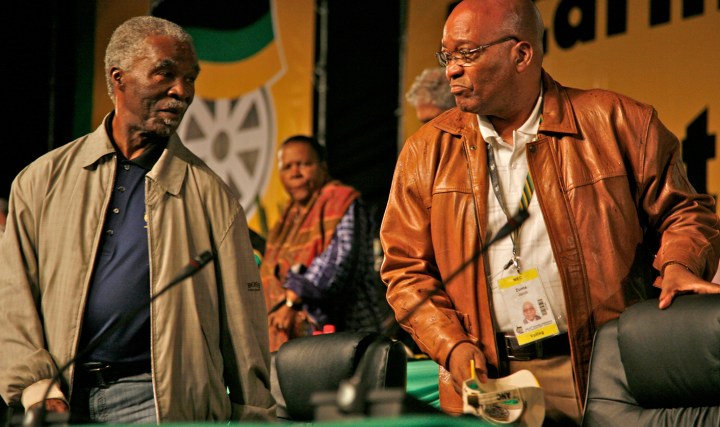

Photo: Jacob Zuma and Thabo Mbeki, Polokwane South Africa 18 Dec 2007. (Greg Marinovich)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider