South Africa

Nelson Mandela was also a great politician – not just the great reconciler

Since Nelson Mandela’s passing last week, the electronic and print media, the public speeches and the public rhetoric have been full to overflowing with encomiums about his success as an unparalleled national reconciler - almost as if he had just been a kind of secular Mother Theresa in trousers. But Nelson Mandela clearly was a man - and a politician - of many parts and many important complexities. J. BROOKS SPECTOR steps back to take the first effort for a more contemplative look at Mandela’s political magic - in comparison with other great leaders.

Over a quarter century ago, during a lazy Sunday lunch, out-of-doors under the warm African sun, my wife and I had joined another couple for the relaxing meal. Eventually, over coffee and dessert, our conversation turned to origins – the origins of our respective political attitudes. On that occasion, our lunch hosts were a UN officer who dealt with the plight of refugees, and his wife. He was a Somali by birth, but he had met his American-born wife while they had both been studying at Brandeis University, just outside Boston, Massachusetts.

He was a committed Muslim and so she, an African American from New York City, agreed to convert to Islam in order to marry him. Somewhat unusually, they had both been attending America’s leading secular Jewish university. After university, he joined the UN and his career had already taken them to many of the world trouble spots – or their more peaceful neighbouring states – by the time we met them.

Although Nelson Mandela would not have been part of our conversation way back then, he just as easily could have been, given the way things went. As our conversation went on, our Somali friend and my wife, both, explained to the other two of us that here in Africa, virtually all students with any kind of a developed social consciousness went through a period where they were communists of a kind. Maybe they didn’t join an actual party, but in their hearts and minds it was as if they were standing out in the cold, in the night, staring hungrily through the window of an inviting restaurant, while trying hard to make sense of the patent unfairness of things.

Marxist analysis obviously offered a way of figuring out how this had come about; it could make intellectual and emotional order out of the apparent unfairness and chaos of events. But even more importantly, perhaps – it offered a kind of roadmap about how to fix things. Combined with the racial critique that spoke more specifically of Africa’s relationship with the West, the resulting mixture of ideas became a powerful tool for grasping what must be done to set things right. Of course those other complexities eventually crept in later, and for many, perhaps most, the Marxist critique eventually was largely set aside as other ways of looking at things become more important.

In retrospect, it seems patently obvious how a bright young, critically thoughtful young adult like Nelson Mandela, early in his political life, could embrace the Marxist message. The real question is: how could he have done otherwise, given the times and the evidence all around him?

The writer is raising this as introduction because, in an fascinating counterpoint to what seems to be an unstoppable wave of warm, fond recollections of Mandela’s essential role as South Africa’s great reconciler – between white and black; between rulers and the ruled; and between oppressors and the oppressed in the crucial years after his release from his quarter century-plus incarceration – an angry, growling debate over the extent of influence the SA Communist Party had on Nelson Mandela has erupted, just as the man has now passed into history. Historians, journalists and social critics have all joined the fray. And by the end of last week, the SA Communist Party itself announced that yes, Mandela had been a member of its Central Committee prior to going into prison. Seemingly even the Communist Party now feels the need to appropriate for itself some of Mandela’s legacy for its own purposes.

But, ultimately, to this writer at least, the question of the impact of Marxist thinking on Nelson Mandela in the early part of his career is much less interesting than several other, still more important questions. The first of these is what of all the other strains of thought that came together in Nelson Mandela’s mind that shaped his ideas and guided his actions once he walked out of Victor Verster Prison on 12 February 1990? The second is whether one can compare Mandela’s own philosophy of leadership with other highly successful world leaders. Did they have anything in common? If so, what might that be? And are there lessons to be drawn from such shared experiences?

As for the first, more than one observer has remarked on the astonishingly old-style courtliness of the man in how he dealt – equally – with the rich and powerful, and those of the most modest of means. In a way, of course, that should not be surprising. As a child, after all, he was part of a household embedded in the carefully defined world of a traditional chiefly family of the Eastern Cape. Then he was sent off to a series of missionary-connected schools, first Clarkbury, then Healdtown and then, finally, Ft. Hare University College.

At each, he was the recipient of a set of values from educators who were profoundly steeped in late Victorian and Edwardian outlooks that must have seemed strongly congruent with many of the traditional values Mandela had imbibed from his larger family circle. Duty, honour, country, steadfast principles, fair play, and being a selfless team player for the group. Never mind that this collection of ideals was being passed along in the midst of a society that was profoundly unbalanced, clearly unfair, and whose fundamental principles were deeply flawed. Regardless, those ideals must have an extraordinary impact on an impressionable young man already eager to demonstrate his talents among his peers – and even to his mentors.

It should come as no surprise that the bit of poetry that seems to have influenced him so deeply, “Invictus”, William Ernest Henley’s statement of indomitable will, was a late Victorian poetic favourite, a praise poem for the ultimate stiff upper lip.

But “Invictus” almost reads like a miniature how-to-do-it manual for Mandela’s evolving core values – and even, eventually, for the form of his unwavering political principles and supple operating style that so animated his mature political style. Older readers will surely recall memorising it themselves for recitations in their English literature classes as well, noting carefully as Henley (an indomitable deist just like Nelson Mandela) speaks of his own triumph over his own hardships. Noting the key bits at the end of each sentence, Henley tells his readers of his spiritual triumph:

Out of the night that covers me,

Black as the Pit

from pole to pole,

I thank whatever gods may be

For my unconquerable soul.

In the fell clutch of circumstance

I have not winced nor cried aloud.

Under the bludgeonings of chance

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Beyond this place of wrath and tears

Looms but the Horror of the shade,

And yet the menace of the years

Finds, and shall find, me unafraid.

It matters not how strait the gate,

How charged with punishments the scroll.

I am the master of my fate:

I am the captain of my soul.

By the time Mandela fled to Johannesburg to avoid an arranged marriage suitable for the son of traditional leader, his initial goal of becoming a court interpreter – an equally suitable occupation for an educated African – were both thoroughly overturned by his work as an attorney for the dispossessed, and his increasing involvement in the world of African politics. In those years, Mandela slowly moved from thinking of “country” as the rural chieftaincy tied to his family, on to Africans the length and breadth of South Africa, then on to everyone besides whites. Ultimately, of course, in the slow grinding of those years of incarceration, “country” became largely synonymous with all people in the nation, regardless of ethnicity. Still, those political urgings also reach right back to those increasingly distant Clarkbury, Healdtown and Ft Hare days and the core value of fair play.

By the time he was released from prison in 1990, his sense of steadfast political principles had become conjoined with a fuller understanding of how gaining success in politics could also arrive via compromise and manoeuvre – and even married with the arts of seduction and flattery – the latter two becoming increasingly valuable talents once he had gained actual office. More than one observer has noted, for example, his success in leading a fractious team in the negotiations that ended the old order came both from patiently building a sustainable coalition between the ANC’s exiles, the former political prisoners and the leaders of the many UDF bodies, the so-called “inziles,” together with a disparate fraternity of international supporters; and then in parleying all of this to out-manoeuvre the National Party government’s negotiators in the drafting of the constitution and the establishment of an interim government.

As president, Nelson Mandela found that much of what he had to do meant, in US President Harry Truman’s well-known, tart observation, that rather than simply ordering things to be done, he spent much of his time “trying to convince some damned fool to do what he should have done in the first place”; and in flattering and beguiling other powerful people to step up with their support for his favoured projects in order to gain Mandela’s appreciation and public approbation.

By the time Nelson Mandela moved on from being president of a notoriously fractious nation, he had earned his reputation as a reconciler, bringing white South Africans into the fold – in part by embracing the national rugby team in its world championship game, and bringing the rest of the nation along with him. Then, when he moved on into retirement, he had gained that reputation as a uniquely competent reconciler-in-chief, both nationally and then internationally as well.

And so that other problem – to whom does Mandela most resemble as a leader – or vice versa – and what do they have in common, if anything? Many people have already compared Nelson Mandela to Mahatma Gandhi, while others point to Winston Churchill as a comparable leader. Both men came from their own societies’ respective upper classes, and they both successfully rose to the challenges of national leadership in times of grave crisis. Gandhi was an implacable proponent of his nation’s freedom and Churchill, of course, came into office in that most existential moment of Britain’s fortunes during the early days of World War II. Both men found a voice that was in near-perfect pitch with their nation’s feelings.

But there is another candidate that to this writer at least also seems to offer grounds for fertile comparison. In the depths of the most severe economic crisis of his nation’s history, Franklin Roosevelt led a nation out of disaster and on to redemption. While Roosevelt never endured time in prison, of course, his own personal crisis was to have been stricken with polio in his adulthood – incurable and unpreventable in his lifetime – forcing him to rebuild his entire way of living, thinking and acting – even, witnesses say, his fundamental character. It gave him a new force of personality – and his own version of an indomitable will to face the trials that would come to him in the 1930s and 40s.

One difference is that when Roosevelt came into office, a guiding principle was to tell his aides that since the current economic crisis was so severe, they would just have to try something to fix things. If that didn’t work, they would move on to something else until they found a tool that worked. In effect, Roosevelt’s guiding principle was ultimate flexibility in the service of the finding success – success was the real measuring stick rather than ideological purity.

But, looked from that perspective, perhaps Roosevelt’s methods were not so very far from Nelson Mandela’s own uses of pragmatism in the service of the greater good of a nation’s freedom, rather than ideological purity. Mandela was a supremely gifted politician, but his gift was to harness the vagaries of an awkward political process in order to achieve his purposes. In that sense, comparing Nelson Mandela – his gifts, his successes and his challenges and his tactics – with others becomes a guide – and a caution – for others who now come after him.

To this writer, however, beyond his political and personal similarities with Roosevelt in so many ways, what stands out most in the life of Nelson Mandela was his decision – like America’s first president, George Washington, or, like Cincinnatus, the general who saved the Roman Republic and then returned to his farm – to retire after he had achieved the task he deemed most crucial and who then stepped aside to allow others to take on the challenges of the future. DM

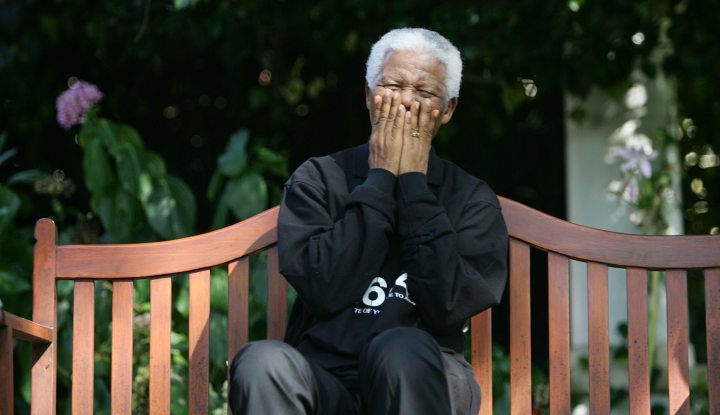

Photo: (REUTERS/Mike Hutchings)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider