Maverick Life

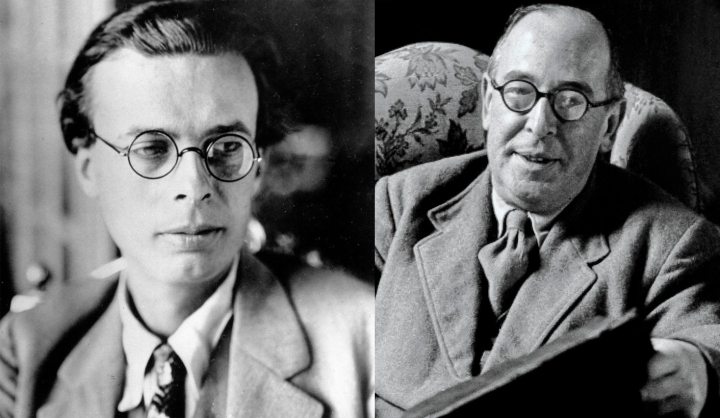

The day JFK, Aldous Huxley and CS Lewis died

If only. If only it had been raining cats and dogs in Dallas fifty years ago and a certain presidential limousine had had its removable top in place; or if Lee Harvey Oswald had had a sneezing fit in the dusty Texas Book Depository building at the same moment the motorcade had made its slow turn at Dealey Plaza. Had that happened, newspapers worldwide would have announced the sad news that two giants of contemporary literature - CS Lewis and Aldous Huxley had passed away instead of John F Kennedy. Instead, their deaths were overwhelmed by the martyrdom of an American president. J. BROOKS SPECTOR looks back at their legacy.

SPECTOR looks back at their legacy.

O wonder!

How many goodly creatures are there here!

How beauteous mankind is!

O brave new world,

That has such people in’t.

— Miranda’s speech, Act V, Scene 1, “The Tempest”, William Shakespeare

Between the two of them – Aldous Huxley and CS Lewis – they were connected to a vast network of literary, scientific and historical figures and their wide-ranging output tackled some of the most troubling issues of the modern world. Between the two of them they confronted the place of religion in modern life (reaching rather different conclusions), the impact of science and technology on faith and the future, and even the very nature of human progress.

Both men were born in the final years of the Victorian era, just prior to the beginning of the twentieth century – Huxley in 1894 and Lewis four years later, living on into an entirely changed world. Their joint coincidental passing could almost be seen to have been almost as notable as the death of literary giants, Cervantes and Shakespeare, on the same day in 23 April 1616 or the political greats, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, on the Fourth of July, 1826.

Aldous Huxley was born into one of Britain’s leading intellectual families. His grandfather, Thomas Henry Huxley, had been a vociferous defender of evolution in print and public forums, right from the get-go; so much so in fact that he was dubbed “Darwin’s bulldog” in the press. And two of Aldous Huxley’s brothers became eminent biologists as well.

Aldous Huxley was a prolific writer – a run of novels, volumes of short stories and essays, numerous dramas and many other occasional pieces flowed freely from him; but, without doubt, his first real foray into the high-end region of science fiction – Brave New World – made him world-renowned. Placed a half millennium into the future, After Ford, Huxley’s 1932 novel spoke of a world where children were bred, hatched or created in giant biology labs and a drug to keep almost everyone calm and serene.

Social critic Neil Postman, comparing Huxley’s Brave New World with George Orwell’s 1984, a book that came out some fifteen years after Huxley’s had and that has had at least as much influence on our understanding of social change as Brave New World, argued that while Orwell feared those who would deprive people of information, Huxley was more fearful that the rulers would give the average Joe so much we would all be reduced to passivity and egotism. If Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us all, Huxley feared more that the truth would be drowned in a sea of ephemera and ceaseless fun – and Soma. Writing in Brave New World Revisited, a non-fiction contemplation of his earlier novel, Huxley had argued then that the civil libertarians and rationalists who were always on the alert to fight tyranny had “failed to take into account man’s almost infinite appetite for distractions.”

Postman noted that the Orwellian world controlled via pain even as Huxley’s “paradise” controlled by the infliction of pleasure. In place of Winston Smith’s great fear of rats, Huxley had held out the guiltless fun of Soma and the rest of it. Looking back on these two versions, the question can at least be asked as to which model looks more like modern society, what with the passing – largely – of fascism and communist authoritarianism? In fact, with just this one work, Huxley had already conjured up sufficient ideas and themes to populate an entire century’s worth of other people’s films, television shows, novels and short stories – as well as the bad dreams and night sweats of political luddites.

Jay Lefkowitz, George W Bush’s advisor on science and medical issues like stem cells, has written in Commentary magazine, for example, about their meeting, just as Bush was coming to grips with some presidential choices in stem cell research.

“I brought into the Oval Office my copy of Brave New World, Aldous Huxley’s 1932 anti-utopian novel, and as I read passages aloud imagining a future in which humans would be bred in hatcheries, a chill came over the room. ‘We’re tinkering with the boundaries of life here,’ Bush said when I finished. ‘We’re on the edge of a cliff. And if we take a step off the cliff, there’s no going back. Perhaps we should only take one step at a time.’ ”

Rightly or wrongly, Huxley’s influence rules from beyond the grave. And in fact, the very title of his astounding dystopian novel has become the watchword for a baleful universe that has bled humanity of its creativity and spontaneity.

While Huxley was well schooled, even steeped in the sciences, as he grew older, he shifted into a life that embraced parapsychology and philosophical mysticism such as Vivekananda’s Neo-Vedanta and Universalism. Moreover, he became a public user of psychedelic drugs, but without Dr Timothy Leary’s or the inhabitants of San Francisco rock scene’s flair for self-promotion of the tune-in, turn-on generation.

But in fact, the dying Huxley, now living in America, nearly blind and body failing rapidly, had asked his wife to inject him, not once, but twice, with LSD for his final trip. (Soma hadn’t been invented yet.)

CS Lewis’ life had a rather different trajectory – spending much of his life in academia at Oxford and Cambridge. Meanwhile, his writing – at least some of it – has found fresh new audiences with vivid, popular film adaptations of works like The Chronicles of Narnia. The Guardian noted that on this, the fiftieth anniversary of his death as well, Lewis ‘will be honoured with a plaque in Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey on Friday.’

His novel, The Screwtape Letters is next week’s Book of the Week on Radio 4, read by Simon Russell Beale, and on 27 November his love life (dramatised in the film Shadowlands) is the subject of a BBC4 documentary, CS Lewis: Secret Lives and Loves. ”

The Guardian argues further that like Lewis’ great friend JRR Tolkien, Lewis may well owe much of his posthumous popularity “to the suitability of his sagas for cinema adaptation in an age when Hollywood primarily targets young audiences and has CGI at its disposal. Attacks from Philip Pullman, who has slated the Narnia books not only as ‘reactionary’ and Christian ‘propaganda’, but as ‘blatantly racist’, ‘monumentally disparaging of girls and women’ and containing ‘not a trace of Christian love’ – seem to have had minimal impact on either Tinseltown types or parents.

Last month plans were announced for a movie version of The Silver Chair, the fourth of The Chronicles of Narnia to be adapted. The three previous films, bound to be hard to avoid on television over the Christmas period, have grossed $1.5 billion worldwide. Perhaps Huxley’s popularity, rather than his intellectual reputation, would reassert itself if Brave New World finally received a full-blown, serious movie treatment, rather than serialized readings on radio and a television mini-series.

Lewis himself wobbled in and out of an embrace of the Anglican Communion (first in Ireland and then in England) during his life. After a period away from religion, he slowly reengaged with Christianity, influenced by arguments with his Oxford colleague and friend JRR Tolkien, and by GK Chesterton’s book The Everlasting Man. He noted later that he was brought back to Christianity like a prodigal son, “kicking, struggling, resentful, and darting his eyes in every direction for a chance to escape.”

In Surprised by Joy, Lewis wrote about his self-conversion experience, “You must picture me alone in that room in Magdalene, night after night, feeling, whenever my mind lifted even for a second from my work, the steady, unrelenting approach of Him whom I so earnestly desired not to meet. That which I greatly feared had at last come upon me. In the Trinity Term of 1929 I gave in, and admitted that God was God, and knelt and prayed: perhaps, that night, the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England.”

As a result of this religious internal conversation, his books, even the science fiction-style works, seem to have reflected this on-going dialogue as well. This writer must confess that while Huxley’s Brave New World was a natural read for him, he never managed to get really engrossed in any of Lewis’ work. Despite the repeated, ardent efforts of my favourite librarian in my neighbourhood public library, a woman who had rarely guessed wrong on how to encourage my evolving literary taste, there was just too much of the whiff of the Church about Lewis’ writing for me – there were too many theological arguments only somewhat dressed up in the enchantments of science fiction.

Obviously millions of others have clearly found his writings to their taste – his novels have been translated into some thirty languages and many millions of copies have been sold – most especially of The Chronicles of Narnia quartet.

Nevertheless, it seems ironic that now that the fiftieth anniversary of the simultaneous passing of Lewis, Huxley and Kennedy has arrived, it is the brace of English authors who are – once again – in the shadow of an overwhelming international commemoration on television and even on the bookshelves of an American president cut down before he could fairly complete his promise. Of course Kennedy did win a Pulitzer Prize with his book, Profiles of Courage, so perhaps literature will get at least one mention on this day. DM

Read more:

- Stem Cells and the President—An Inside Account at Commentary

- CS Lewis and Aldous Huxley’s afterlives and deaths at the Guardian

Photo: Aldous Huxley/CS Lewis.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider