Maverick Life

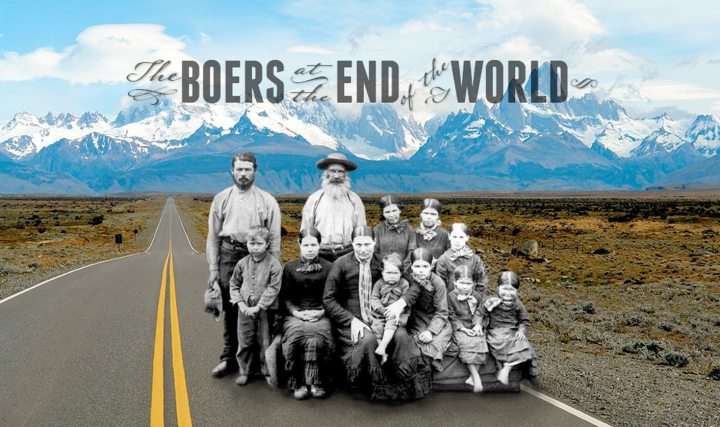

The Boers at the end of the world

In a remote corner of Patagonia, a community exists to whom Sarie Marais is a familiar ditty and melktert is sold in the local café. They are the descendants of Afrikaners who travelled across the ocean to Argentina around 1903, lured by the prospect of land and a new life away from the hated British. In 1965, a Sunday Times journalist wrote that in this area, “more Afrikaans than Spanish is heard in the shops”. Today only a handful of the Patagonian Boers remain who can understand Afrikaans. A Cape Town filmmaker is determined to document their world in an upcoming film titled “The Boers at the end of the world”. By REBECCA DAVIS

“As soon as I heard this story, I knew it was an amazing one,” says filmmaker Richard Finn Gregory. He’s referring to the curious phenomenon of Afrikaans-speakers in Patagonia who have never set foot in South Africa and have only a hazy sense of the country’s history. Every few years, a journalist seems to remember their existence and sallies forth to write a feature: in 2011 Ricky Hunt wrote a wonderful story on the Patagonian Boers for the Mail & Guardian. While Tony Leon was South Africa’s ambassador to Argentina, he met with the group at least once.

This year they were in the news when a South African journalist launched an appeal to collect Afrikaans music to send to the Argentinean town of Sarmiento. There, older individuals will apparently break out the accordions and perform a rousing rendition of ‘Sarie Marais’ and ‘Suikerbossie’, which has sparked the curiosity of at least one youngster to investigate his heritage. The journalist planned to send him the music of Bles Bridges and other Afrikaans singers.

The locals of the area may look and sound like Argentinians, but they have surnames like van der Merwe, De Lange, Botha and Venter. There is a bay in the province of Chubut called “Puerto Visser”, after one of the original 1903 Afrikaner settlers – a man from Barkly East called CJN Visser.

In 1902, the Boers had just lost their hard-fought war against the British. Whether Argentina seemed like an attractive prospect because of their economic losses or because of their resentment of the British, is a question historians apparently still quarrel over. In 1991 the New York Times visited the community and reported that some still harboured a grudge against the British. One 79 year-old, Enrique Grimbeek, told the newspaper that he had attempted to enlist to fight the British during the 1982 Falklands War.

But there was also a solid economic incentive for them to make the journey across the seas. According to Ancestry 24, each settler family was given 625 hectares of land free by the Argentinian government, which knew that the Boers could make farming work in tough conditions. They were then required to buy a further 1,825 hectares of government land.

The area around the port of Comodoro Rivadavia, where they settled, is by all accounts inhospitable. “The paved road hugs the coast straight kilometre after straight kilometre, through empty wilderness, like a precarious umbilical cord of civilisation,” a 2010 feature in De Kat described. “There are no trees to break the monotony of barbed, hip-height shrubs; no hills pierce the flat horizon.” A particular problem initially was the lack of a water source. When the Boers received permission to drill for water, they ended up hitting oil.

As numerous writers have noted, in another context this discovery could have made them rich. But in Argentina, the mineral rights belong to the state. Even today, the Boer descendants live humble lives as farmers. “You’ll see no Afrikaners here who are well off,” a 67 year-old man called Danie Botha told Tony Leon when Leon visited Comodoro Rivadavia in 2009.

The toughness of Patagonian life caused many of the original settlers to turn tail and head home when offered the chance. In 1938, to accompany the centenary celebrations of the Great Trek, the South African government arranged the repatriation of those who wished to return. Between half and two-thirds of them chose to do so. The number of Boer descendants who live in Chubut today is uncertain, but Leon told the M&G in 2011 that he had been informed by the community that they number several hundred.

The extent to which Afrikaans continues to be spoken is also unclear, but it is inevitably dwindling as the older generations die off. The younger descendants speak Spanish. “Na my geslag is daar nie meer Afrikaans nie [After my generation there will be no more Afrikaans],” 75 year-old Carlo de Lange told SAPA in 2009. The community reportedly asked the South African embassy for an Afrikaans teacher a few years ago, though it may not have materialised.

“I had heard from others who had gone to Argentina to visit the Boer community that they hadn’t been able to find anyone who could still speak fluent Afrikaans,” says filmmaker Gregory. “They basically told me that it was a myth that there were still people who spoke it. Well, of course that just made me more determined, and I’m now in close contact with some of the last Afrikaans speakers there, so it’s certainly not a myth.”

Gregory hasn’t yet travelled to Argentina to start shooting his documentary, but aims to do so in the next month or so. He is ‘crowdfunding’ the movie via the website Indiegogo, and says that the public response has been very warm because there are people with a “strong interest” in seeing this story told. Nonetheless, Gregory still has a short way to go before meeting his funding target.

“I want to show a portrait of how the community looks today,” Gregory says. “From my discussions with them, I get the impression that they feel somewhat caught between two worlds: feeling the tug of history in their Boer heritage and Afrikaans language, but being surrounded by contemporary Argentine culture. They are keen to preserve their traditional culture, but with the globalisation of the modern world, they have become less insular, and assimilation into the local population seems inevitable.”

Gregory aims to bring some of the “Argentine Afrikaners” to visit South Africa for the first time, and track down their distant relatives. Knowledge of South Africa among the third-generation Patagonian Boers seems sketchy: one journalist wrote that they refer to their ancestral homeland as being “Africa” rather than South Africa. When the New York Times tried to get the community to discuss race issues and Apartheid in 1991, they appeared “mystified”.

“All I know is that out here the servant and the master are the same,” one told the journalist. “They eat the same food, ride the same horses and sleep on the same land.”

It is possibly this aspect that has led to some of the mythologising around the group; the notion of a Boer community unsullied by Apartheid. “You need not be an inveterate Afrikaner nationalist to feel a deep affection for them,” suggested Andre Pretorius in a 2010 feature for De Kat. “They speak our language, they are ‘our’ people, in an untainted, wholesome way – we share something not conditioned by the complexities of 20th century history.” DM

Read more:

Become an Insider

Become an Insider