Africa

Bashir in Juba: more symbol, less substance

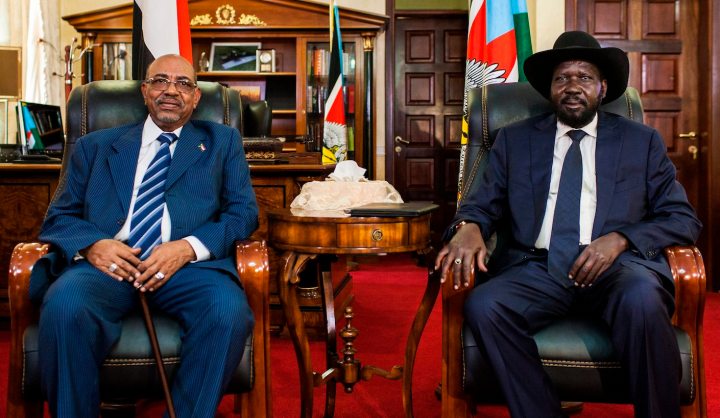

Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir was in Juba this weekend, visiting the leader of a country that he once ruled. In practical terms, the visit didn’t achieve much, particularly when it came to the hot-button issue of what to do about the Abyei region. Symbolically, however, it was a breakthrough in what is a very tense relationship between Sudan and South Sudan. By SIMON ALLISON.

The last time Omar al-Bashir arrived in Juba, he technically ruled the place. That was two years ago, shortly before the southern half of his country voted to secede, but even then his authority was limited: after a decades-long civil war, and six years after the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, Juba was already well on its way to becoming what it is now: the capital city of Africa’s newest country.

Still, as Bashir returned to Juba on Tuesday, it must have been a strange feeling to return as a mere visitor to a city that he once dictated to. If nothing else, it’s a powerful symbol of just how much has changed in this part of the world – little of it for the better, as far as Bashir is concerned (as well as the economic crisis precipitated by the loss of the oil-rich south, he’s fighting to hold on to his own position in the face of internal dissent and popular discontent).

Despite the long and bitter history between Bashir’s regime in Khartoum and the new South Sudanese government, Bashir was received with full diplomatic honours by South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir. The two leaders know each other well from countless negotiations in various African countries, as well as from the long stint that Kiir served, just prior to secession, as one of Bashir’s vice-presidents (an appointment that was part of the terms agreed in the peace treaty). Their strangely fraternal relationship mirrors that between the long-serving members of the two countries’ negotiating teams, which is genuinely warm and affectionate at times.

The two presidents had plenty of nice things to say after their meeting, both determined to ensure that the visit was a success – superficially at least. “The meeting with my brother Salva Kiir was fruitful…. We will make sure all the outstanding issues are implemented,” said Bashir, while Kiir emphasized that “We are ready to go the extra mile to make peace with Sudan”.

While there was no shortage of brotherly love on display, actual solutions to the very real and dangerously volatile issues between Sudan and South Sudan were harder to come by. In fact, the talks yielded little of substance, except pro-forma declarations to implement agreements made in other forums.

The lack of progress was especially obvious when it came to Abyei, the region on the border of the two countries that is a constant flashpoint. Abyei had its own section in the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, and was meant to have its own referendum in 2011 to decide whether it wanted to remain in Sudan proper or move over to South Sudan’s jurisdiction. This referendum is yet to happen, mostly because no one can agree on who should participate in it.

Abyei hosts two main communities: the settled, pastoral Dinka Ngok tribe and the semi-nomadic Misseriya. The Misseriya are only in the area for a few months a year, but argue this should not disqualify them from a say in Abyei’s future. The Dinka Ngok, meanwhile, contend that as the area’s only permanent residents, it’s their voice that counts.

Complicating matters is that the Misseriya are, broadly-speaking, aligned with the Khartoum government, while the Dinka Ngok identify with the south. To resolve the eligibility question is therefore to determine the result of the election, one way or the other.

Complicating matters even further is that for sides, Abyei is a hot-button political issue. Although Abyei does have oil, that’s not the real problem as the area’s most recent borders (agreed to by both parties) exclude any major fields. Instead, Bashir is worried about the prospect of losing even more territory, given that the secession of the south was deeply unpopular with his core constituency around Khartoum, and he got much of the blame; and for Juba it’s a very useful rallying tool to unite its disparate and argumentative population (as explained by Eric Reeves in his comprehensive timeline of the Abyei issue).

Even as Bashir was glad-handing in Juba, the Abyei situation took a possible turn for the worse, with Sudan’s military reported to be engaging in a build-up of planes and aircraft at a key base at Kadugli in the border province of South Kordofan. The Sudan Sentinel Project, which uses satellites to monitor military activity, said that the build-up “could signal planned deployments toward several locations, including the highly contested Abyei area.” Another likely target is the Sudan Revolutionary Front, a rebel coalition operating with considerably success in South Kordofan.

As usual, the conflict in South Kordofan (and neighbouring Blue Nile) is disproportionately impacting the civilian population. Hundreds of thousands of people have been forced into refugee camps in South Sudan by the fighting, while there have been thousands of civilian deaths, largely due to Khartoum’s indiscriminate bombing campaign. Despite Khartoum’s active involvement, and Juba’s alleged support for the rebels, a source within the Sudan Revolutionary Front said this conflict was not discussed at all by Bashir and Kiir.

Bashir’s visit, then, didn’t achieve very much – no new agreements, no progress on Abyei, and not even a mention of South Kordofan and Blue Nile. This doesn’t mean, however, that it was a complete dud. That the two sides are talking at all is a good sign; that the two presidents are talking, in person, is a potent symbol that there is potential for negotiation and dialogue. The next step, however, is for the two of them to actually agree on something – an altogether more demanding proposition. DM

Photo: Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir (L) poses for a photograph with his host, South Sudan’s President Salva Kiir, at the latter’s office in Juba. (REUTERS/Adriane Ohanesian)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider