South Africa

Limpopo textbook debacle: Oh, what a tangled web

Civil society organisation Section27 has just released a case study it commissioned on the 2012 Limpopo textbook crisis. It’s a reminder of just how messy that saga was, and in particular the frightening degree of obstructionism that seemed to characterise the Department of Basic Education’s response to the problem – including the alleged firing of whistle-blowers and alleged threats from the highest levels against Limpopo teachers and principals who dared to speak out. By REBECCA DAVIS.

When Section27 began investigating the non-delivery of textbooks to Limpopo schools in January 2012, they couldn’t have guessed that the problem would, to quote the report they’ve just released, “with Nkandlagate and the Marikana massacre, become [one of] the main issues to dominate the local socio-political landscape in 2012”.

One of the reasons was the length of time it dragged on for: the issue’s final court airing was in October, eight months after concerns were initially raised. Another was the seeming inability of either the provincial or national department of education to resolve the problem with any speed or efficiency. But arguably the major reason why the issue hogged headlines and discussions was because it seemed to epitomise an education system in crisis – and an education system whose Minister publicly denied it to be in any crisis.

Independent researcher and lawyer Faranaaz Veriava, who authored the report, told the Daily Maverick that she was interested in the matter from the start, as someone who has been involved in education rights. “When I first started following the case, what struck me about it was the way it ignited the indignation of many South Africans across the political spectrum, and the way it drew attention to the issues in education.” After all, she points out, the problem of learners not receiving textbooks is not a novel phenomenon in South Africa. “At the beginning of every year we read media reports that textbooks are not delivered to classrooms and then the story goes away and the public forgets about it until the following year.”

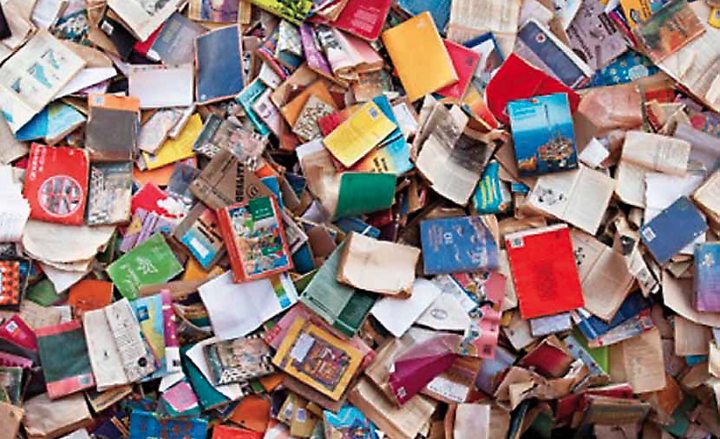

What made the Limpopo saga different seems to have been the scale of the issue, the confluence of management problems in the province more widely, and the fact that a media-savvy advocacy group stuck with the story and litigated shrewdly. Media reports and photographs of dumped textbooks throughout Limpopo also kept public outrage ignited, since those pulped books were handy visual shorthand for the endangered educational prospects of Limpopo learners.

It took three court orders and the best part of a school year for the necessary textbooks to be delivered to Limpopo schools. It’s worth noting, as the report does, that in the court judgments delivered by Judge Jody Kollapen, he never suggested that the non-compliance of the education departments was willful. “Indeed he acknowledged the difficulties experienced by the DBE [Department of Basic Education],” the report states.

But at least some of these difficulties were due to the incredibly poor systems in place in the Limpopo education department. EduSolutions, the company contracted under dubious circumstances to the tune of R320 million to provide textbooks in Limpopo, took over the entire textbook procurement process from the time of taking up the contract in May 2010. This meant that the whole Limpopo database, detailing the number of schools in the province and the number of books they needed, was handed over to EduSolutions – and when the company’s contract was terminated, almost unbelievably, the DBE was left with none of this information.

This provided one of the major recommendations of the Metcalfe Report commissioned by government to look into the textbook saga: that “if key functions of government such as the procurement of textbooks are outsourced, all data must remain the property of government”.

It seems a rather obvious point, though the DBE continued to blame EduSolutions throughout the crisis rather than the systems that permitted the data disappearance. Indeed, while the DBE was no doubt placed in a difficult situation with regards to procuring the necessary textbooks after EduSolutions failed to do so, the report hardly paints the department in a glorious light.

For one thing, the DBE downplayed the urgency of remedying the textbook situation by denying that the textbooks were essential to the learning process; only “complementary”. But the report maintains that the textbooks were indeed essential, because they were an integral part of the 2009 shift to the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS), which required that teachers be more structured in their lesson plans. Through the use of the CAPS textbooks, the aim was to seek uniformity so that variations in the amount of knowledge teachers possessed wouldn’t harm the students.

“The Limpopo textbook case was thus not only about ensuring that every learner has access to a textbook,” the report says: “it was also about ensuring that teachers are adequately equipped in the classroom.”

Then there’s the fact that various individuals who tried to raise red flags at certain points were either ignored or dealt with more sinisterly. For instance, the Publishers Association of South Africa (PASA) had noticed that textbook orders were missing from Limpopo before the start of the 2012 school year, and had contacted the Director General of the DBE, Bobby Soobrayan, to find out what the problem was. PASA followed up three times without receiving a response from Soobrayan or the department.

Other whistle-blowers were dismissed. Acting CFO of the Limpopo education department, Solly Tshitangano, raised concerns over the irregularities of the EduSolutions contract and was fired. Dr Anis Karodia authored a report on the parlous state of the Limpopo education department in March 2012, which was subsequently leaked. The Minister of Basic Education was allegedly “very unhappy” with the content of the report and Karodia was fired in May.

(Karodia, admittedly, sounds like a less than stable force: the report quotes Section27 staff as describing their conversations with him as “surreal”, as he attempted to portray himself as “the heroic and hidden hand trying to clean up the LDoE [Limpopo department of education]”. Here’s a quote from Karodia during a meeting with Section27: “You can go tell the media and I will correct you and tell them what I told you. I don’t know why I left the greenery for this mad house. I don’t know who is who in the zoo. This is the wild, wild west and everybody has a horse and a gun.”)

It is also alleged that Limpopo teachers and principals were the subject of intimidation by officials within the LDoE, including principals being threatened with having their jobs removed when they accepted the help of Section27, which also claim they received an email from an anonymous teacher in Limpopo in August 2012 which stated: The Minister of Education came to our district and threatened us not to talk to the media about the book shortages if we value our careers. Even now I don’t want my name to be known cause I will risk losing my job.

The DBE also spent an estimated R900,000 taking out half-page ads in Sunday newspapers last October to try to persuade the public that Section27’s litigation was “unnecessary and a waste of valuable time and resources”. It’s a sign of the strained relationship between the two sides of the court cases at that time. Indeed, one factor mentioned in passing in the report is that the failure of the DBE to adhere to the timeframes for book delivery set by the court may have been partly due to “an undercurrent of resistance and resentment on the part of the DBE in being compelled into action by the litigation”.

This would appear to be one of the risks of this kind of government-targeted litigation by civil society. Another is that there is a limit to how effective such litigation can ever be when there are deep systemic problems underlying service delivery problems. The report states: “The litigation initiated by Section27 sought to ensure that the learners’ right to a basic education be realised by the delivery of textbooks. The limiting nature of this litigation meant it could not directly address the issues of dysfunction and corruption within the LDoE, which ultimately resulted in learners not receiving their textbooks.”

Inasmuch as this type of litigation drains state resources, diverts energies, seems to set up a fundamentally adversarial relationship between government and civil society, and may not even succeed in fixing the problems it sets out to, then — is it, on balance, worth it?

“The law on its own cannot achieve the change that we need to see in education,” concedes Section27 advocate Nikki Stein, who was part of the team leading the legal challenge. “Legal processes are always a last resort. In the textbooks case, we gave the department of education numerous opportunities to deliver textbooks without going to court. The urgency of the case separates it from some other cases, where there is more time. But I think that, even though the time constraints forced us to go to court quickly, the case has resulted in increased social mobilisation around education in Limpopo.”

One of the biggest successes of the textbook case, to Stein’s mind, was the attention it brought to the national education crisis and to the specific collapse of the Limpopo education department. “The case was one of the reasons that people started to talk about education and to demand the quality basic education they are entitled to under the Constitution,” Stein says. “I think that there is a bit more faith in the law and its power in realising basic rights. There is a move towards holding department officials accountable.”

Veriava says that the LDoE and Section27 now enjoy a “co-operative relationship”, which has been useful in dealing with subsequent issues, such as that regarding sanitation in schools. “So while the litigation was acrimonious when it was ongoing, I think it has also provided insights that this country would not otherwise have had,” she says. “Most importantly, it also placed pressure on government to improve systems for textbook delivery, not just in Limpopo but nationally.” DM

Read more:

- Section27’s 2012 Limpopo Textbook Crisis report.

Photo by Section27.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider