Maverick Life

Bone marrow transplant: a donation that saves a life

A bone marrow transplant can be the only way of saving the life of an adult or child with a terminal bone marrow disorder like leukemia. But only 30% of such patients will be able to find a bone marrow match within their own family. For 21 years, the South African Bone Marrow Registry has worked to attempt to match South Africans with donors outside their family – and often outside the country. One of their patients recently flew to Taiwan to meet the donor whose bone marrow saved his life. This is his story. By REBECCA DAVIS.

The year 2013 marks the ten-year anniversary of a diagnosis that was to turn Amrith Singh’s life upside down. Johannesburg-based Singh, who works within freight logistics, was 35 years old in 2003, when he was diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukemia.

“They initially put me onto oral medication, and it didn’t work. I started getting jaundice and my liver was affected,” says Singh today. “We stopped for a while, and then tried again. I started getting weaker and weaker and doctors proposed a bone marrow transplant.”

Singh’s siblings were tested to determine whether they could serve as donors for their brother. But as happens in over 70% of cases, a match for Singh’s bone marrow could not be found within his own family.

Over 21 years ago, that might have been pretty much it for Singh, because prior to 1991 South Africa had no bone marrow registry. Neither was there any on the whole continent, in fact; only now is a fledgling registry in Nigeria getting going. Professors Ernette du Toit and Peter Jacobs resolved to take matters into their own hands, launching the South African Bone Marrow Registry (SABMR) within the Laboratory for Tissue Immunology that Du Toit headed. In the same year, the SABMR was approved to access international donors from the World Marrow Donor Association.

The SABMR explains that the process of matching bone marrow patients with donors is complex and technical. The odds are 1 in 100,000 that a match can be found. Today the SABMR has access to more than 20 million donors worldwide through their pooled international registries. “Anyone doing a search all over the world can look and see where there is a donor, and what level of match there is,” explains Terry Schlaphoff, deputy director of the SABMR.

The SABMR also has a registry of South African donors, which numbers around 65,000 currently. Any healthy individual between 18 and 45 is eligible to register as a donor. Initially a blood sample is taken to determine the tissue type, and if you are matched with a patient, your stem cells are “harvested” over the course of two days in a procedure they describe as involving “minor discomfort”.

But in 75% of South African cases, the SABMR finds its matches overseas through searching the international registries. Amrith Singh’s bone marrow could not be matched with that of any local donors on the registry. “So we turned to the international registry because I was getting very sick,” Singh says.

The search for a donor to match the patient can take anything from a few weeks to many months. In Singh’s case, a match was found with a donor in the Far East in 2005, but the donor withdrew shortly before the transplant. Fortunately, another prospect presented itself.

“We found a donor that was a possible match in Taiwan,” says Schlaphoff. “What happens then is that we get a sample from the donor brought here to double-check, because we can’t do all the matching on paper. We never know the names of the persons: it’s totally anonymised. All we know is their year of birth and their gender.”

Singh’s donor was not a 100% match. “But I was tired and didn’t want to wait,” Singh says. So plans for transporting Singh’s donor cells from Taiwan to Johannesburg were put into action – a process the SABMR describes as a “military operation”.

“The cells have to be transported by a human who needs to have them in eye contact at all times,” says Schlaphoff. “If you go to the toilet on your flight, the cells go with you.” They are transported in a container resembling a cooler-box, and arrangements are made with airport security in advance so that the box does not have to be X-rayed, which might affect the cells.

In 2005, Schlaphoff flew to Taiwan herself to fetch Singh’s donor’s cells, liaising with the Buddhist Tzu Chi Stem Cell Centre in Taiwan. The donor was to give his cells in the city of Hualien, on Taiwan’s east coast. Upon arrival in Hualien, Schlaphoff was collected by a “little grey-habited lady, a Buddhist nun called Wendy”, who announced that a typhoon was about to hit the island. Under strict instructions to stay inside, Schlaphoff waited it out anxiously in her boarded-up hotel, while winds reached 250 km per hour. The local hospital was largely evacuated – but a skeleton staff remained behind to harvest the cells of Singh’s donor.

Photo: SABMR deputy director Terry Schlaphoff, pictured in Taipei after having collected the vital cells.

Schlaphoff got the precious cells and was able to get out on the first flight after the typhoon. Touching down in Johannesburg, she took the sample straight to the transplant centre. After Singh’s “conditioning” – readying his body for the procedure – the transplant took place early in August 2005. A transplant is not a guaranteed cure in this situation, as complications after the procedure are possible. Singh, however, responded well to the treatment.

“It was tough for about three or four months and then my body started taking it and I got stronger,” says Singh. “In 2006 I was able to return to work.”

Though many patients feel enormous gratitude for their donors, there are strict rules governing the contact that they are allowed to have with each other. “We allow anonymous correspondence at any time,” Schlaphoff explains. “We encourage a thank you letter.” Beyond anonymous letter-writing, though, the registries advise at least five years before making any contact, including via email.

“For some patients there is the need for more [cells], and the feeling is that the donor may feel pressured if they have met the patient,” Schlaphoff says. There is also the potential for the donor to attempt to benefit inappropriately from the transplant in future – for instance, by asking for money from the patient. Then there’s also the possibility that the donor and patient may suffer distress from realising that they don’t like each other. Schlaphoff says it’s been known to happen that a “morbid attachment” may develop between the two, where they feel compelled to have constant contact.

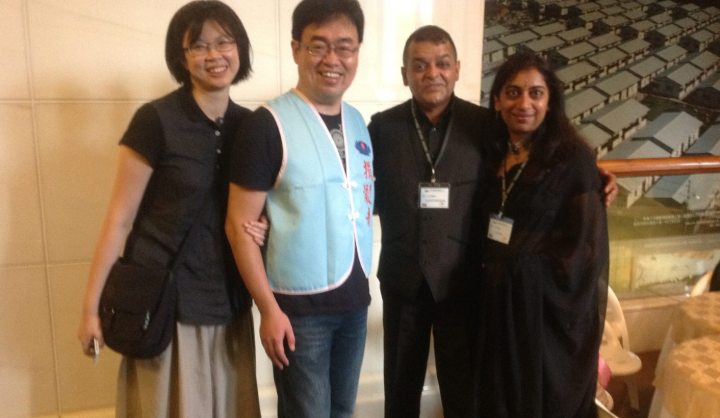

Singh says that he thinks these rules are necessary and good, but when the chance arose to meet his donor in September this year, he leapt at it. The Buddhist Tzu Chi Stem Cell Centre celebrated their 20th anniversary this year, and invited Singh back to Taiwan to meet his donor as part of an international conference. He was the only African present to have received cells from Taiwan.

“On the way there I was very, very nervous,” Singh says. He knew nothing about his donor in advance, but he turned out to be a Chinese man of 38. “I thought of questions before. I had so much I wanted to tell him, but when I got there I just let my heart do the talking.”

When Singh was called on stage to meet his donor, he went to him and got down on his knees before him. Then he rose and hugged him. “They asked me afterwards, why did you get down on your knees?” Singh says. “It’s a form of respect. He saved my life.”

The two men were given an interpreter to facilitate a short conversation. “When he gave the donation he was about to get married. It was part of his nature,” says Singh. “Talking to him, you grasp what a humble person he is. He is genuine from his heart. He didn’t want anything out of it.” The two did not exchange details when they parted, but Singh says he would love to meet him again: “He is like a brother to me now.”

Back home in Lenasia, Singh says his health is now stable. “I go to the doctors once a year. So far it’s all been fine, though I can pick up a flu at any time. I try to eat consciously and to exercise a little. But I live life. I still do the things I enjoy. I have my braais – when I was sick I always dreamed of it. My family is very close. I have two sons, and we all spend as much time as possible together. Previously I was very conservative when it came to doing things, but now I appreciate life much more.”

Singh says he will never forget the gift given to him by his donor. “He is my saviour,” Singh says simply. “He has given my siblings a brother, my children a father, and my wife a husband.” DM

To find out more about joining the SA Bone Marrow Registry, visit http://www.sabmr.co.za/

Main photo: Johannesburg’s Amrith Singh (second from right) and wife Kirti meet his bone marrow donor and wife. (SA Bone Marrow Registry)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider