World

Fifty years after The March on Washington, a dream remains a dream

As the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington approaches, the American administration readies for a celebration, and President Barack Obama readies his own speech from the steps. It’s an occasion that provides an opportunity to reflect on the momentous words of Martin Luther King Jr and the equally momentous cultural changes that followed. In doing so, it is essential to ask what has changed, and what work remains. By J BROOKS SPECTOR.

At 3pm on 28 August 1963, on the front steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, before a crowd estimated at somewhere between 200,000 to 250,000 (and many more via live television) young and old, the 34-year-old Rev. Martin Luther King Jr stood before the world and began his “I Have a Dream” speech. A simple set of engraved words now mark the precise spot on the Memorial steps where King stood that afternoon.

The date, the hundreds of thousands who gathered there, King’s speech and the symbolism of the Lincoln Memorial joined together in perfect synchronicity in a vivid representation of the aspirations for civil rights for all. In fact, that very same site had been used before – 24 years earlier – for a demonstration for equal rights that cast the template for the 1963 event now etched into national memory and which turned the Lincoln Memorial into national sacred ground.

Years earlier, on 9 April 1939 (Easter Sunday) more than 75,000 people came together at the Lincoln Memorial – a monument completed in 1920 in memory of the country’s 16th president – to witness an open-air recital by famed African American contralto Marian Anderson. Her Washington concert had originally been booked for Constitution Hall, but the owners of the hall, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), had refused to allow Anderson to perform on its stage (it would have been a violation of its whites-only policy, in what was still a thoroughly segregated national capital).

Watch: Marian Anderson sings in front of Lincoln Memorial, 9 April 1939

In response to that decision, first lady Eleanor Roosevelt resigned her membership in the DAR in protest and secretary of the interior Harold Ickes arranged for Anderson to deliver her concert from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial instead. The concert instantly became a seminal moment for the country’s nascent civil rights struggle and the combination of Anderson’s concert and the Memorial’s symbolism honouring the president who ended slavery in America made that site the inevitable location for any future civil rights demonstrations.

In 1941, in the early years of World War II, A. Philip Randolph, the leader of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (a predominately black labour union then at the peak of its prominence in the country) had threatened to lead a major protest march on Washington to force an end to discrimination in the hiring for war production and strict segregation in the armed forces. The presumed potential of Randolph’s planned march to generate national disruptions convinced then president Franklin Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8802, which would end wage discrimination in war industries, but not within the military itself. (The military remained segregated until 1948.) In return for this decision by Roosevelt, Randolph agreed to call off the planning for that promised march in 1941, but the idea of holding a major civil rights march on Washington remained with him for decades.

By the early 1960s a new generation of civil rights figures, people like Rev. Martin Luther King and Rev. Joseph Lowery of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Roy Wilkins of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP) and John Lewis of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (and today a congressman from Georgia since 1987) were in the forefront of an increasingly vigorous civil rights movement that was leading a broad assault on national discrimination. This movement had already been carrying out sit-ins at segregated lunch counters, engaging in legal actions to gain court decisions to desegregate southern school districts, and conducting voter registration drives, marches and boycotts to force the desegregation of public facilities across the southern states for more than half a decade. And, of course, a number of African Americans and their white supporters had been arrested, assailed and dispersed in marches and demonstrations by police who used police dogs, water canons and truncheons whenever orders to disperse went unheeded.

Then, in early 1963, Randolph’s long-cherished dream of a March for “Jobs and Freedom” was resurrected. Put into the operational hands of veteran organizer Bayard Rustin, a vast coalition of organizations that included church groups, civil rights advocacy groups like the NAACP, the National Council of Negro Women and other women’s associations, as well as national labour unions, were all summoned to cooperate in bringing nearly 300,000 people together in Washington, DC to provide a powerful but peaceful affirmation of shared civil rights values.

In so doing, the March organizers managed to achieve a coalition in which each group had different approaches, and sometimes even different agendas. By the time the March was set to go, the explicit demands from the organizers had become much more than simply a straightforward civil rights agenda.

Beyond legal discrimination, in the minds of organizers there was an extensive economic justice agenda as well. As a result, the stated objectives for the March included passage of meaningful civil rights legislation, the elimination of racial segregation in public schools, protection for demonstrators against police brutality, a major public-works program to provide jobs, the passage of a law prohibiting racial discrimination in public and private hiring, a $2 an hour minimum wage and local self-government for Washington, DC, which had a black majority population. At that time, DC was effectively run by two congressional committees, chaired by segregationist Southerners and with a majority of members who were similarly Southerners and supportive of segregation.

Officially, at least, there were six main organizers. They were James Farmer of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), Martin Luther King Jr of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), John Lewis, of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), A. Philip Randolph, Roy Wilkins, of the NAACP and Whitney Young Jr of the National Urban League.

To make the March a success, working in a way that would have rivalled a mass military campaign and carried out from a largely improvised command centre, Bayard Rustin and his team of volunteers meticulously organized the whole thing, right down to the smallest detail. Without computers, the Internet, e-mail or social media they used thousands and thousands of notations on index cards and wall charts to plan the March’s progress.

To manage the expected massive crowd, March planners recruited off-duty police and firemen from across the country to volunteer as rally marshals. They scheduled bus and rail transportation and then bus parking throughout Washington at predetermined staging areas, and then coordinated security with the Washington Metropolitan police and the leadership of Army National Guard troops that had been called up for duty during the March by federal officials. In their pursuit of detailed planning, organizers even debated what would be better to put into the bag lunches they planned to distribute to many in the crowd – chicken salad vs. ham and cheese sandwiches – keeping the intense August heat and humidity in mind.

Photo: Bayard Rustin (Wikimedia Commons)

In addition to the public figures providing the entertainment and the speeches, Rustin was the real unsung hero of the March. But there were several reasons why the big names associated with the March decided to keep Rustin’s name and role deeply in the background. In part they wanted to avoid accusations of “outsider agitation” that might have been levelled at the March if Rustin’s role and personal circumstances had been better known. Rustin was a practicing Quaker, a social activist-conscientious objector of World War II who had even served jail time for adhering to his convictions during the war. As a result, he was sometimes accused of being some kind of radical socialist agitator. Worse still, he was a barely closeted gay man at a time when such behaviour was still criminalized throughout America. But he was such an organizational genius his talents simply could not be ignored if the March was going to succeed.

As the actual March brought the vast crowd to the Memorial and the surrounding lawns, besides all the speeches, there were musical interludes by stars including musicians Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Josh White, Mahalia Jackson, the group Peter, Paul, and Mary and even Marian Anderson. Charlton Heston – representing a contingent of artists that included Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Diahann Carroll, Ossie Davis, Sammy Davis Jr, Lena Horne, Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier – read a speech composed by writer James Baldwin.

Watch: Bob Dylan and Joan Baez perform at March on Washington

All the “Big Six” civil-rights leaders gave speeches, although James Farmer, who was incarcerated in Louisiana at the time, had had to have his read by a colleague, Floyd McKissick. There were prayers from Catholic, Protestant and Jewish religious leaders. And there was a speech by Walter Reuther, the head of the powerful United Automobile Workers whose members had helped increase the number of attendees at the March. There was only one female speaker, however. Josephine Baker was given the role of introducing “Negro Women Fighters for Freedom,” a group including Rosa Parks, the woman who had refused to move to the back of the bus in Montgomery, Alabama so as to make way for a white passenger boarding the bus, thereby precipitating the bus boycott protest in that city.

As far as the nation’s political leadership was concerned, then president John Kennedy had originally tried to discourage the March, worrying it might well make a Southern-led Congress dig in its heels and vote against future civil rights laws in response to what would have been perceived as a direct threat. However, once it became clear the March would happen with or without his support, he withdrew any public objections. Although individual labour unions like the UAW had actively joined in support of the March, labour’s national leadership of the AFL-CIO union federation remained officially neutral.

Meanwhile, there was outright opposition from two very different political directions. White supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan (still a potent force in Southern states) were obviously opposed to any event that would have supported steps towards legal racial equality. However, the black separatist Malcolm X also publicly condemned plans for the March, calling it the “Farce on Washington”. It was further announced that any members of the Nation of Islam who participated in the March would face disciplinary suspension.

Watch: Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech

As the crowd gathered in its vast numbers from mid-day onward, speeches and entertainment filled the air but none of these speeches touched a nerve so as to become a nationally revered moment of public oratory. By mid-afternoon, when Martin Luther King stepped forward to deliver his 15-minute address, he was to give the speech of a lifetime. He began with a nod towards the works of Abraham Lincoln and the fact the rally was taking place at the steps of the monument in Lincoln’s honour. That noted, King moved quickly to stake out his own rhetorical territory. “One hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land.”

In saying this, King asserted the time had come to redeem the metaphorical cheque of the promises in the country’s Declaration of Independence by telling the crowd, “It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of colour are concerned. Instead of honouring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’”

Nonetheless, King also argued that while the bank of justice was not yet bankrupt, there was a “fierce urgency of now”, and that “Now is the time to lift our nation from the quick-sands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” He cautioned the March should not be viewed as a bit of blowing off steam by the disenfranchised. Rather, “The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.”

Even as King demanded the marchers must be paid their due from the nation, he also reminded black Americans that they “must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force” without giving in to racially based anger and mistrust.

Instead, “for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.”

In a kind of self-generated call and response, to those who would ask when black Americans would be satisfied, King replied, “We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: ‘For Whites Only.’ We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until [in the words of the Biblical Book of Amos] ‘justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.’”

King then consoled those who had already struggled long and hard for the cause of civil rights, launching into his most famous lines, “Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends. And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’

“I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

“I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

“I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today!

“I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of ‘interposition’ and ‘nullification’ [tactics that were supposed to render unwanted federal law and Supreme Court decisions null and void] – one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.”

Drawing again from a Biblical text, this time he drew upon the words of Isaiah, “I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; ‘and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.’”

King then offered an audacious verbal riff on the lyrics of the song, “America” (the very same music Marian Anderson had sung to open her concert on those same steps a quarter of a century earlier) from which he would pivot to his final peroration, “And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!”

The speech now resonates through the decades as it has been justly regarded as one of the most important and powerful evocations of a nation’s hopes. As an aside, Robert Kaiser, then a very junior reporter for the Washington Post, noted ruefully that somehow in its lead article the following day the Post managed to nearly forget to report on King’s speech, focusing instead on the peacefulness of the March and the words from the other speakers. Sometimes a self-evident truth only becomes so after the fact.

And then the March was over, successfully, and it was time to go home. Well, not quite. The March did not mean the federal government immediately took all the steps that had been demanded in the marchers’ ambitious legal and economic agenda. In fact, passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and then the 1965 Voting Rights Act would only come when then president Lyndon Johnson, himself a Southerner, took upon himself the burden of getting those proposals passed into law. Insistent he would bring to fruition the Kennedy ideals after Kennedy had been assassinated on 22 November 1963, Johnson even adopted the informal motto of the civil rights movement when he addressed a joint session of Congress on 15 March 1965, saying to the nation, “We shall overcome”.

Watch President Lyndon Johnson – Speech on Voting Rights

And this week, Americans from all over the country have been gathering in Washington to mark the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington in events that run from 24 -28 August. On that final date, former presidents Carter and Clinton will join incumbent President Obama as he delivers his own speech to the nation on the same spot, and at the same time, as Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” address took place.

And so, is the civil rights struggle in America now concluded fully and successfully? For that question public opinion polls and survey data offer a more anomalous answer. Despite all the legislation passed into law and the real changes in de facto as well as de jure legal circumstances, a new report from the Pew Research Center finds fewer than half (45%) of all Americans still believe the country has made substantial progress toward racial equality. Slightly more (49%) say that “a lot more” remains to be done.

Significantly according to the Pew report black Americans “remain more downbeat than whites about the pace of progress toward a colour-blind society. They are also more likely to say that blacks are treated less fairly than whites by police, the courts, public schools and other key community institutions.” Moreover, “significant minorities of whites agree that blacks receive unequal treatment when dealing with the criminal justice system. For example, seven in 10 blacks and about a third of whites (37%) say blacks are treated less fairly in their dealings with the police. Similarly, about two-thirds of black respondents (68%) and a quarter of whites (27%) say blacks are not treated as fairly as whites in the courts.”

Nevertheless, “The survey also finds that large majorities of blacks (73%) and whites (81%) say the two races generally get along either ‘very well’ or ‘pretty well.’ Similarly, large majorities of Hispanics and whites say the same thing about relations between their groups (74% and 77%, respectively). A substantial majority of blacks (78%) and smaller share of Hispanics (61%) say their groups get along.” However, a touch more than a third of blacks surveyed say they had been the subject of discrimination or have been treated unfairly because of race – although 20% of Hispanics and 10% of whites say the same thing about themselves.”

The Pew Center comments on this data, “the economic gulf between blacks and whites that was present half a century ago largely remains. When it comes to household income and household wealth, the gaps between blacks and whites have widened. On measures such as high school completion and life expectancy, they have narrowed. On other measures, including poverty and homeownership rates, the gaps are roughly the same as they were 40 years ago.”

In economic terms, in the aggregate, the Pew data explains, blacks earn about 59% of white income, a modest rise of 4% from 1967 levels (although in absolute dollar terms the gap has actually increased slightly). And black unemployment has been approximately double that of whites since the 1950s. Significantly, the percentage of black men incarcerated in federal, state and local prisons is more than six times those of white men, even higher than was the case 60 years ago.

The Pew data also shows there “has been a fading of the heightened sense of progress that blacks felt immediately after Obama’s election in 2008. Today, only about one-in-four African Americans (26%) say the situation of black people in this country is better now than it was five years ago, down sharply from the 39% who said the same in a 2009 Pew Research Center survey. Among whites, the share that sees improvement in situation of blacks also fell, from 49% to 35%, in the last four years. For both blacks and whites, the latest finding on this question is returning to the levels recorded in a Pew Research Center poll in 2007 on the eve of the Great Recession.”

Clearly, more work needs to be done and the dream remains at least partially unfulfilled. How Barack Obama will draw upon his own considerable rhetorical powers on Wednesday to encapsulate the hopes and dreams, as well as to address the stumbling blocks that remain in achieving equality may be a crucial test of the president’s ability to connect with the nation’s hopes and aspirations, even as he must somehow reach across the racial boundaries of today’s America. DM

For more, read:

- Civil Rights March on Washington (History, Facts, Martin Luther King Jr.), at Infoplease.com

- ‘The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom, and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights ’ by William P Jones, a review by Jonathan Yardley, at Washington Post

- Five myths about the March on Washington, in Washington Post

- What would Martin Luther King Jr say to President Obama? By Congressman John Lewis, in the Washington Post (Lewis spoke at the March in 1963)

- 50 Years After March, Views of Fitful Progress, at New York Times

- Despite ‘Enormous Strides,’ Minorities Still Face Barriers, President Says, at New York Times

- March to focus on continued fight for civil rights, at AP

- An overlooked dream, now remembered, at Washington Post

- Marching for King’s dream: ‘The task is not done’, at AP

- US Celebrates 50th Anniversary of Civil Rights March, at VOA

- Martin Luther King Jr’s dream still echoes, at Washington Post

- Thousands march to Mall to mark ‘Dream’ anniversary, at Washington Post

- ‘Free at last,’ Mandela said, quoting King, at Yahoo (and AP)

- Letters from and to King on South Africa, at the King Center

- A dream deferred, at Financial Times

- Who Designed the March on Washington? A column by Prof Henry Lewis Gates, at The Root

- Thousands rally in US to mark ‘I have a dream’ speech, at BBC

- MLK’s Children: They Have a Scheme, at The Root

- King’s Dream Remains an Elusive Goal; Many Americans See Racial Disparities, at Pew Research Center

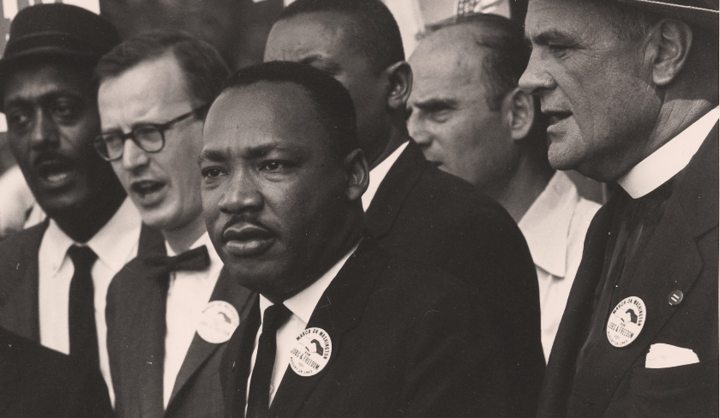

Photo: Martin Luther King speaks, March on Washington (Wikimedia Commons)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider