Africa

Analysis: Angola illustrates the dangers of criminal defamation laws

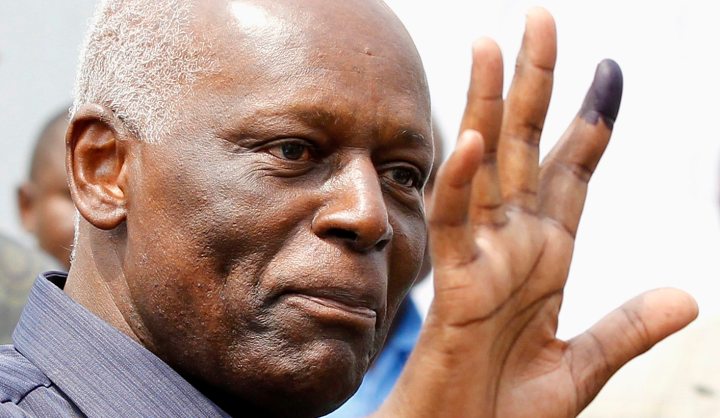

South African media reacted nervously when a former Sowetan journalist was found guilty this week of criminal defamation. This was not an over-reaction, if the example of Angola is anything to go by. Do we really want to be taking media management lessons from José Eduardo dos Santos? By SIMON ALLISON.

After years of neglect, just as journalists were beginning to put this particular nightmare behind them, South Africa’s courts resurrected the nasty Apartheid-era principle of criminal defamation to protect one of their own.

Cecil Motsepe, a former journalist for the Sowetan, was convicted earlier this week of defaming Gauteng magistrate Marius Serfontein. Motsepe had accused Serfontein of being lenient on white defendants, and Serfontein took offence. Serfontein insisted that the issue be prosecuted as a criminal matter and Motsepe was duly sentenced to ten months in prison or a fine of R10,000 (suspended for four years). (For a full breakdown of the case, and the legal principles involved, read Rebecca Davis’ excellent analysis.)

It’s tempting to dismiss this case as a one-off. It was, after all, the result of a judgment call from an angry magistrate looking to protect his reputation. And Motsepe had made a significant factual error, which seriously undermined his claims. Besides, journalists should be held accountable for their mistakes, right?

This, however, misses the point. Of course journalists should not be allowed to cast aspersions at will and must be responsible for the words they write. But there are methods of redress that do not involve potential jail time – a complaint to the Press Ombudsman, perhaps, or a civil defamation suit, which is a far more usual course of action in these circumstances.

The civil route has two major advantages as far as the complainant is concerned. First, the burden of proof is much lighter in civil cases (on balance of probability rather than beyond reasonable doubt). And second, the complainant has the chance of receiving financial compensation from the defendant. The criminal route, on the other hand, is purely punitive and runs the risk of discouraging the kind of brave, principled journalism vital to the health of any democracy.

For a good example of how criminal defamation laws work to restrict good journalism and freedom of speech, we need not look far. In Angola, the principle is being used to shut up one of the few independent journalists left in the country.

Rafael Marques de Morais has been a thorn in the side of José Eduardo dos Santos’ government for more than a decade. First with an independent newspaper, and then through his Maka Angola blog, Marques has exposed a string of corruption deals and human rights abuses that have embarrassed officials occupying the very highest positions in the state. He’s also written two books, The Lipstick of Dictatorship and Blood Diamonds: Corruption and Torture in Angola.

It’s this last book that has now landed him in hot water. In it he describes more than 100 instances of serious human rights abuses committed by military personnel and private security guards in Lunda Norte, Angola’s diamond belt. He also names names, implicating a number of senior generals in the abuses.

The generals, predictably, weren’t happy and in 2012 tried to sue Marques for criminal defamation in Portugal, where the book was published. The Portuguese prosecutor threw the case out, saying that Marques had a right to publish information that was so obviously in the public interest.

In 2013, the generals tried again, this time in Angola, slapping him with 11 criminal defamation suits (breaking Angola’s double jeopardy law in the process, given that Marques has already been cleared of these charges in Portugal). The charges are vague, and neither Marques nor his lawyer have been allowed to look at the evidence against him, making it impossible to formulate a proper defence.

The case has drawn sharp criticism from international NGOs. “These actions appear to be part of a wider pattern of criminalization of investigative journalism in Angola,” said a coalition of 16 organisations (including Freedom House, Corruption Watch, Transparency International and the Committee for the Protection of Journalists), in a petition to Angola’s attorney general to drop the charges. In a separate statement, Human Rights Watch’s Leslie Lefkow added: “The cases against Marques show exactly why criminal defamation laws are a problem: they can too easily be abused and used for politically motivated purposes.”

The Human Rights Watch statement is worth quoting in more detail, because it illustrates exactly why the criminal defamation law is such a problem: “Defamation is a criminal offense under Angolan law, and in recent years a number of journalists have been prosecuted for criminal defamation in lawsuits brought by senior government officials. Many of the legal provisions to protect media freedom and access to information are vaguely formulated in Angola’s 2006 press law, which limits the ability of many journalists to criticize the government publicly without fear of repercussions.

“Human Rights Watch, along with an increasing number of countries and international authorities, believes that criminal defamation laws should be abolished, as criminal penalties are always disproportionate punishments for harming a person’s reputation and infringe on free expression. Criminal defamation laws are open to easy abuse, resulting in very harsh consequences, including imprisonment. As repeal of criminal defamation laws in an increasing number of countries shows, such laws are not necessary for protecting reputations.”

For authoritarian governments, however, criminal defamation laws are incredibly useful tools to keep those pesky, muckraking journalists quiet. Not that it has worked on Marques. Showing incredible bravery, the journalist has initiated a little legal action of his own, suing Angola’s vice-president for conflict of interest. In addition to his government role, Vice-President Manuel Vicente is administrator of the Chinese-owned China Sonangol oil company – a clear violation of government rules, which state that ministers can’t hold corporate positions.

Clearly, the criminal defamation suits won’t keep Marques quiet. But he won’t be able to report on much if he is convicted and given jail time, and the suits may well discourage other journalists from making sure the rich and powerful stay on the straight and narrow, which is what good journalism is really about.

As the principle of criminal defamation rears its ugly head again in South Africa, the example of Marques and Angola should serve as a warning. Let’s do whatever we can to make sure our government doesn’t take media management lessons from Dos Santos. DM

Photo: Angola’s President Jose Eduardo dos Santos shows off his inked finger to photographers after casting his vote during national elections in the capital Luanda, August 31, 2012. REUTERS/Siphiwe Sibeko

Become an Insider

Become an Insider