South Africa

Fifty years on: Remembering the Liliesleaf arrests

On 11 July 1963 police raided Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia and arrested the high command of Umkhonto we Sizwe. The arrests resulted in the Rivonia Trial at which eight accused – Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki, Andrew Mlangeni, Raymond Mhlaba, Ahmed Kathrada, Elias Motsoaledi and Denis Goldberg – were sentenced to life in prison. RYLAND FISHER speaks to the founder of the Liliesleaf Trust, Nicholas Wolpe, about history and the future of the farm.

The men were charged with sabotage under the General Law Amendment (Sabotage) Act of 1962 and sentenced on 12 June 1964.

Mandela had been arrested at Howick the year before and sentenced to five years in prison. He was brought from Robben Island to be accused number one in the Rivonia Trial. He had earlier stayed at Liliesleaf while he was involved in underground activities for the ANC and Umkhonto we Sizwe.

The Rivonia Trial, and the subsequent Little Rivonia Trial, had the potential to completely destroy the ANC and internal resistance to apartheid. It began a period of consolidation and growth, mainly in exile, for the ANC who had earlier been banned by the apartheid government.

Liliesleaf is now a centre of memory. Carrying the baton for it and the history of a decisive era for South Africa is the founder and chief executive of the Liliesleaf Trust, Nicholas Wolpe.

Wolpe was born on 16 April 1963, a few months before the arrests at Liliesleaf. He is one of three children of Harold and AnnMarie Wolpe, who fled into exile shortly after Harold escaped from detention just before the start of the Rivonia Trial. Nicholas returned from exile in 1991.

He tells Daily Maverick about the 50th anniversary commemorations, his plans for Liliesleaf, and his frustration at the marginalisation of history in schools

Your parents were very central in the struggle against apartheid. How old were you at the time of the arrests at Liliesleaf?

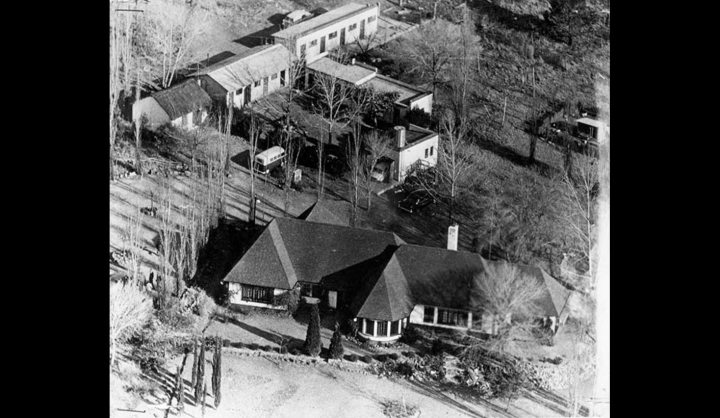

I was born in April 1963, so I was nearly three months old when the raid took place. I was nearly four months old when Harold (Wolpe) and Arthur (Goldreich) broke out of prison. I don’t have recollections of that time, but I remember as an eight, nine or 10-year-old, looking at that iconic picture of the house which all the newspapers carried. I remember looking at that picture quite a lot in my uncle’s book, wondering what this place Liliesleaf symbolised and how Harold was connected to it and to the events that subsequently unfolded. I had looked at the press cuttings my mother collected. It was quite interesting how the relevance and importance of Liliesleaf never jumped out, because very few people had done any detailed research or written about the place. My earlier recollection is of that picture in my uncle’s book, A Healthy Grave.

(Wolpe’s uncle was James Kantor, who had been one of the accused in the Rivonia Trial. He was acquitted, along with Rusty Bernstein.)

Growing up as the child of political activists, was there pressure on you to follow in their footsteps?

No, not in the least. In fact, of my three siblings I was the one who probably rebelled the most in the sense of distancing myself from the ANC and political involvement. What is quite interesting is that in 1990, after Nelson’s release, my two sisters were adamant they were not going to return to South Africa. I, on the other hand, was clear in my own mind that I was coming home. Throughout that period, when they were old enough, they were quite active in the ANC in some form or other. Throughout my childhood, into my teens and into my early 20s, I kept quite a distance from the activities of the ANC.

How did you end up having to take responsibility for Liliesleaf?

In 2001, the then treasurer general of the ANC Mendi Msimang came to me and said I needed to organise an event to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the formation of MK. As you know, 16 December 1961 is generally considered to be the birthday of MK with the announcement of the attacks that followed that day.

They wanted me to organise an event at Liliesleaf. Why Liliesleaf? I don’t know, because at that time the information was not available. I organised a reunion and just felt that we couldn’t allow the history of Liliesleaf to fade from the historical narrative and landscape. I presented the idea to establish the Liliesleaf Trust, and to buy back the three properties on which the historical structures had been situated on to start the process of the legacy project. They agreed.

The arrest of the leadership took place on the 11 July 1963. How do you plan to commemorate that at Liliesleaf?

In 2011 we came up with a programme of memory and legacy to ensure that unique periods of our liberation struggle are not forgotten. Liliesleaf forms a very important role in this, because it is a place of memory. Our programme of memory and legacy involves the commemoration of the raid of Liliesleaf, the escape from Marshall Square and the start of the Rivonia Trial.

A gala dinner will be held at Liliesleaf on 11 July, but it is not just about that. We have been running a series of programmes and events, in the lead-up to the anniversary and this will continue throughout the year to ensure this is not just a once-off event. We don’t just want a gala dinner event and then forget about it. It is something that needs to be perpetuated in the minds and consciousness of everyone to ensure we don’t just celebrate one date.

We must ensure the essence and meaning of what this place symbolises, articulates and represents, continues long after. We must continue to remember these seminal dates, because one of the problems we face in this country is forgetting our liberation struggle and a lot of our history. It just doesn’t seem to feature. No one seems to consider it of importance or relevance.

I’m one of those who advocate the importance of preserving our collective history, whether it is the negative or positive. For instance, I believe that Vlakplaas needs to be restored, because it tells a particular aspect of our history, regardless of how painful and traumatic that history may be. It forms part of that mosaic of who and what we are as South Africans.

No one has gone and obliterated Auschwitz’s books and levelled the sites associated with it, yet they are associated with the worst of human atrocity that man has committed. They are standing there today as sites of memory. People visit them because they tell a particular story which needs to be told. This is part of memory and legacy.

Do you know what happened to the farm after the arrests?

The farm was actually sold to a German who bought it as a wedding gift for his girlfriend. She recalls that she would only be allowed to come here when her mother from Germany came out, because her mother was chaperoning her. He eventually took it back from her because they never got married. The property was then sold to a property development company who sub-divided it into dwellings.

You bought back the farm in 2000?

The first purchase took place in 2002 and we bought three properties on which we thought historical structures were situated. We knew the house existed, because it was there. We knew the thatch cottage was there, because it was the maid quarters for the property next door – 9 Winston Avenue. At the back was 9 George Avenue.

I recall the architect saying to me in one of our earlier meetings, “Nick, we don’t think any of the historical structures related to the out-house buildings still exist. We think that they have most probably been demolished.”

Over an 18-month period we were able to uncover the original three structures in various degrees of preservation. One of the first out-house buildings had actually been badly damaged and turned into a garage. Most of the rooms were demolished, but they still had some of the original structures standing.

You call this a historical site and not a museum.

Actually, I call it a place of memory. I think it is very important because without wanting to delve into the philosophical debate around museums, I believe there are various types of museums. Most museums are man-made and have specific things: you go and view pictures and historical artefacts.

Then there are sites of memory that have played significant roles within history and contributed towards the history of a particular country. What comes to mind are the cabinet war rooms in the United Kingdom, where Churchill oversaw the World War II. Liliesleaf is the same. It is a site of memory. It is a site where activities and events actually happened. It is different to a museum. In my opinion, a museum is manmade, whereas this has evolved out of history.

Why should people come here and what special experience will they have when they visit?

Apart from the fact that it is a site of memory, I think there are very specific reasons why people should come here. It tells a history of a very unique seminal period in our liberation struggle. People say if you really want to understand the meaning of the struggle and appreciate it, you must first come to Liliesleaf because it articulates that. I believe that it gives voice, meaning and expression to our Freedom Charter, which is our most seminal docket. Our Bill of Rights and Constitution grew out of this document.

It was the place that became the nerve centre of our liberation struggle, for just shy of 20 months. It became the diaspora of the liberation struggle. Various structures met here. It became the high command of Umkhonto We Sizwe. It was from here that they launched their first attacks. It was here that the Operation Mayibuye document was written and debated.

It is very rich in history and it gives context to various other events that followed after the raid on Liliesleaf. If you want to understand why the Rivonia trial came about, why Mandela landed up at the Rivonia trial, you must first start out here because it contextualises it, because the raid on Liliesleaf led to the Rivonia trial. The Rivonia trial got its name from the fact that Liliesleaf was in the peri-urban area of Rivonia.

It also explains what happens to the internal liberation struggle following the raid. It is generally agreed that following the raid, the subsequent Little Rivonia trial and the Bram Fischer trial, there was this hiatus in internal liberation activity. It was basically decimated.

I have spoken about Liliesleaf being a site of memory. The importance of that is to ensure that our memories of our liberation struggle, the events of our struggle, are not forgotten. We are at a very serious crossroads in this country where our liberation struggle is being forgotten. The names synonymous with our liberation struggle are being forgotten and not being recognised. The only one is Mandela, but there are many others who played just as important and as key a role as him. Liliesleaf, as a site of memory, has a moral responsibility to ensure those names and those events are not lost or forgotten.

It is clear to me there was a significant financial investment in Liliesleaf to restore the buildings but also the technology you employ. Where did the bulk of the money come from?

We are very unique. We epitomise the true meaning of public-private partnership. Money from the National Lottery and government accounts for about 45% of our funding, while the balance comes from the private sector, directly and indirectly through their foundations. To date, we have raised nearly R130-million, which has gone to purchase the land. It is also being used to maintain and run the site, to develop the buildings and build the infrastructure, and to develop the exhibits and do research.

Do you struggle to raise funds at all?

We do. One of the interesting things that we are now beginning to experience is that we are not deemed an educational site in line with what the BEE charter and the ICT charter specifies. I find this quite ironic given that what we experience today, to a large extent, can be traced back to Liliesleaf. What happened there created those very conditions for where we are today. But today it is excluded from receiving funding from certain corporates who say giving us money does not form part of the BEE charter scorecard.

How do we make sure that young people understand this history and visit places like Liliesleaf?

That is a very interesting point you have raised and it is a point which, I believe, has created a lot of contestation and, to some degree, is being avoided. If you look at our educational system, we are obsessed with mathematics and the sciences. I would even go as far as to say that we have introduced a form of Thatcherite education policy. If you look back at [Margaret] Thatcher’s education policies when she came into power, the social sciences received a hammering. They were marginalised, they were considered to be inferior. They were considered to be pointless. They did not contribute to the value-add of economic growth.

To some extent the same thing is happening in South Africa today. The social sciences are being marginalised. That can be seen by the fact that history is not compulsory beyond a certain age. If you look at Cuba as an example, if you want to get into university, you must have history. History is seen as a central subject, as an important feature.

How do we ensure that the youth of today understand, appreciate and acknowledge what the liberation struggle meant, what many people in South Africa went through?

Mlangeni said in a recent article in the Sunday Times he is sick and tired that material possession and wealth accumulation have usurped the liberation struggle. The only thing people are interested in today is making money. Where are the traditions of the struggle?

Part of that is education. The state and the private sector need to put history first and put our liberation struggle first. They need to put the history of our country first, by making history an important part of the curriculum.

We need to acknowledge that science and mathematics are critical subjects but they must not be pushed to the detriment of the social sciences, particularly history, because it gives us an understanding of who and what we are.

We must ensure that schools play a major role in educating the youth. But I believe the media also has a role to play. The media has to some extent what I would call liberation fatigue. They don’t respond positively, they don’t embrace it. They don’t cover it.

At the moment there is an interest because of Mandela’s health. If his health was not of such major interest, I don’t think the interest that Liliesleaf has seen over the past few weeks would have been there. The media must play a role in keeping our history alive.

Places of history, such as Liliesleaf, need to promote the importance of our heritage and the role that it plays. This is where government comes into play. I saw an advert in the Sunday Times where the national heritage agency is asking people to write in with their memories of important sites in our history so that it does not fade. But this is not enough.

There needs to be a political commitment, willingness and desire. The fact that the department of arts and culture does not have the word “heritage” in it is a problem, because it immediately sends out a message that our heritage is not a central feature.

Heritage Day is now referred to as “Braai Day”. It has been relegated to almost a euphemism, not of history but of braaiing, and that’s the problem.

What’s next for Liliesleaf? What are your plans for the next couple of years?

I have three very clear plans for Liliesleaf. The first one is to continue developing the oral research that we have undertaken. We want to build up a comprehensive oral history of the liberation struggle.

Recently, we did interviews with people around the Freedom Charter, not so much about the writing of it, but more of the logistics that went into organising this phenomenal gathering.

We want to continue to build Liliesleaf and the exhibits to ensure it continues to convey the information that is pertinent and relevant, and to develop our archives to make them accessible. One of the things I believe is that archives need to be accessible. There is this impression that you create an archive and then you throw away the key so that no one gains access to it. What’s the point of having an archive if you don’t make it accessible to people to use as a resource? It’s almost as good as just letting it die.

The second thing is to develop Liliesleaf from a technical point of view, to make it an interactive and dynamic place of discovery, a place of enlightenment. You must be able to go on a journey of intrigue and discovery, learning about aspects of the struggle, not only the political but also the human aspects.

We need to look at the interesting connections, the conspiratorial theories, the ideas that float around. Our role is not to be judgmental but to convey the history. It is for you, the visitor, the historian and the researcher, to determine not necessarily the authenticity of what we present, but to what extent you can accept what is being presented as valid and correct.

I want to make Liliesleaf one of the world’s leading historical sites by combining the first two with the technology. It needs to become a cutting-edge, leading historical site, and one of the leaders in the world.

We now have a project underway that will link it to the iPad, which will allow you to test all the exhibits from your iPad. You won’t need to leave the ticket office and will be able to explore all the exhibits at your fingertips.

That is really the goal that I have for the next three to five years, to ultimately make it one of the world’s leading and foremost historical sites and to show that Africa is capable of delivering world-class, state-of-the-art spaces, institutions and places of memory. DM

Photo courtesy of Liliesleaf Trust.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider