South Africa

Leaders’ health: From a deep secret to open information

South Africa’s national psyche now seems almost entirely consumed by the status of Nelson Mandela’s declining health – and the way in which this status is being communicated to the people of South Africa and the world. Much of the current anguish received a real kick-start at the beginning of this year when officials led the media and public on a wild goose chase around Gauteng, admitting, denying, letting slip, and then denying yet again, before it became clear – unofficially – in which hospital Nelson Mandela was actually being treated for pneumonia. By J BROOKS SPECTOR.

In fact, the uproar over an even earlier hospitalisation of Mandela had led to a more centralised approach to public information in the Presidency about Mandela’s health issues – after a previous hospitalisation seemed to pit the Presidency, the Mandela family and the Nelson Mandela Centre for Memory in a three-way tug-of-war over who was taking the lead in communicating about the globally revered former president’s health. There is now so much concern about Mandela’s precarious health that it has virtually overwhelmed public attention about the impending visit by US President Barack Obama to South Africa.

Moreover, over the past week, there has been official (and some public) annoyance about reports on a US television network – subsequently repeated by South Africa’s media – over Mandela’s precarious health. The report had said that when Mandela was being rushed to a Pretoria hospital early in the morning, the ambulance carrying him broke down en route, the former president’s heart had had to be resuscitated and that, consequently, official guidance on his medical circumstances had been at variance with what had happened to him.

Flowing from this is a debate between the media and the Presidency – and among the media and media analysts – about how best to handle this on-going medical drama, as it may be about to enter its final act. On one side is the assertion international and South African media have very different approaches to a story like this. The argument goes that while foreigners are in it for the story, the glory and the headline, regardless of the cost to people, somehow South Africans are more reluctant to traduce the privacy of a national icon like Nelson Mandela and his family – at this difficult hour. Undercutting this view, of course, is the fact the moment the story broke on the CBS TV network, local media were prepared to run the story themselves. (There is also the inconvenient fact for this theory of decisive national differences that a South African reporter working for CBS did the reporting.)

University of the Witwatersrand Journalism Professor Anton Harber (himself a seasoned reporter and editor) has recently written on this topic that “South African news operations are hiding behind their international colleagues on this one. They would be lambasted if they did not show the utmost respect for Mandela’s privacy, making it always likely that they will leave their international colleagues to make the running on this. News24 started by carrying the official denial of the CBS story as a way to get into it. M&G online was reporting that CBS is reporting it. By Sunday morning, the local were using the CBS report to call into question the government version. Are the authorities telling us the truth about Mandela?” Thus, is there really a major difference between South Africa and, say, America in the way in which detailed information would be reported on a leader?

Added to this mix is that, if one listens to numerous government figures, and even some media types, much of this presumed western, or American, approach to the reporting of personal facts is assumed to stem from some kind of desire by journalists to dig up every bit of private, privileged detail on a famous man’s final days – simply for the joy of revealing this information for their nefarious motives like beating the opposition with the latest scoop regardless of their impact on people.

But, in truth, the South African media has, in fact, traditionally been rather free in reporting the minutest details of certain kinds of issues like crimes – and the criminal accused. Back in the bad old days, the writer is convinced he recalls stories headlined along the lines of, “Businessman Found in Love Nest with Coloured Beauty.” The headline would be followed by details of yet another transgression of that supposedly sacrosanct “colour line”. More recently, one only has to think of the way private, personal details in the Oscar Pistorius matter have consumed the local media. Personal, private details may not really be the issue, despite those who argue there is an implicit right to privacy about medical issues for public figures. Rather, this may just be one more version of a tussle over government control over the right to know by the public.

The other day, after President Zuma had given his briefing to the press, the one where he argued he simply couldn’t provide details beyond the term “critical”, the writer spoke with one of the government’s senior message managers who also was attending that meeting. When it was suggested that a more consistent, routinised, authoritative briefing – including the participation of a physician – could help alleviate some of the angst and ambulance chasing now going on, the government official brushed off the idea, arguing it would never work, it would only feed the media frenzy further, and it would make the press pursue the issue even more breathlessly. They were, are, and would be entirely relentless on this. The media were, in a word, “unstoppable”.

Perhaps, however, this is the case precisely because the media feel they have been fed less than a diet of the whole truth during this extended saga. This is especially true after that earlier run-around over which hospital Nelson Mandela was actually receiving treatment in; what had happened during his post-midnight ride to the hospital, or how his condition had changed from that of him doing well, laughing and talking with family and friends, to serious, and then on to critical – all with very little in the way of serious explanation.

In fact, is all medical information necessarily private, personal and privileged? Not, perhaps, if one compares the way similar tasks are carried out in other democratic nations. The real key seems to be ensuring the public gains just enough information so that it is not spooked by sudden downturns – or worse. While Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, is obviously not in the same category as Nelson Mandela in terms of his being a global political icon, the British royal family and its government seem to believe that while the Duke’s entire medical history and all of his test charts needn’t be released to the public; nevertheless, during his most recent hospitalisation they have been issuing regular, albeit short, medical bulletins that have been sufficiently clear and frequent to have reassured people concerned for him.

In America, in recent years, certainly, it has become a virtual rite of passage in the quadrennial presidential campaign that the medical and health circumstances of the major candidates for the presidency are released to the public. As National Public Radio could report in 2008, “During his first run for the White House in 2000, Republican John McCain released details about his bout with melanoma. And he has promised to release his full health records soon.” Once elected, the overall results of a president’s annual physical exam similarly get explained publicly – the implicit idea is that a senior public official’s health is not a private, personal, privileged item at all. Instead, it is, at least in part, an important element of the nation’s public fund of knowledge.

Back in 1972, Senator Thomas Eagleton, of course, ran up against public fears about psychological treatments when he had had to speak about his shock therapy for depression years before he had become a candidate for the vice presidency. This late-coming admission drove him off the Democratic Party ticket that year. Eagleton had famously announced, “On three occasions in my life, I have voluntarily gone into hospitals as result of nervous exhaustion and fatigue. As a younger man, I must say, I drove myself too far, and I pushed myself terribly hard, long hours, day and night.” And that was end of it for him in national politics. Probably the last candidate who attempted to seriously underplay his medical conditions was Massachusetts Senator Paul Tsongas, who insisted during his unsuccessful run for the Democratic nomination for president that his treatment for lymphoma had been fully successful – although he passed away three years later from that same disease.

Increasingly, as presidents undergo surgical procedures and treatments, the public has been kept more fully informed. It is now routine to see a physician – or even a team of them – brief the media on presidential operations or treatments. When Ronald Reagan was wounded in an assassination attempt in 1981, soon after his major emergency surgery, the physicians gave a briefing in a conference room of the hospital (however, they did elide around questions of his state of consciousness during those emergency procedures. This, in turn, generated a brisk, after-the-fact discussion about whether or not the 25th amendment to the Constitution – the one that deals with presidential disability – should have been invoked at that time.)

Of course this openness come about incrementally. Health Media Lab comments, “Over the past century, the health of our presidents has become a political as well as a medical issue. Beginning with Chester Alan Arthur’s [who suffered from Bright’s Disease] administration in 1881, the perceived political consequences of disclosing a president’s medical problems have sometimes conflicted with the public’s concern for accountability and openness. Presidents Arthur and Kennedy chose to keep their incurable diseases secret. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, on the other hand, advocated full disclosure.

Back when Grover Cleveland was operated on for cancer of the jaw in 1893, in order to avoid spooking further an already-falling stock market and faltering national economy then in full financial panic mode, the surgery was carried out secretly on a small yacht at anchor in the river off Manhattan. And his lengthy recuperation was termed publicly to be just a long-needed mountain vacation. The NPR adds that, quoting historian Robert Dallek, “When Woodrow Wilson ran in 1912, ‘he’d already had a series of small strokes.’ Toward the end of Wilson’s second term, he had a stroke that left him totally disabled. His wife essentially ran the White House for 18 months.”

Franklin Roosevelt, of course, was elected four times while confined to a wheel chair. Rather than be the poster boy for the heights a handicapped person could reach, he and his advisors chose to keep his disability out of view – and the White House press corps and everyone else went along with this occlusion of fact. Moreover, when he was an increasingly sick man in 1944, neither his electoral opponent (nor anybody else) ever raised his health as an public issue. It was only after his death that the extent of his illnesses became more generally known. But by contrast, when Dwight “Ike” Eisenhower suffered two major heart attacks while in office, while his doctors did minimise the extent of the danger to his life from those attacks, they did provide regular briefings to the media.

By contrast, Eisenhower’s successor, John Kennedy’s full medical history was never actually made public – let alone his growing dependence on pain blockers and stimulants to cope with degenerative bone injuries from WW2 combat and the effects of Addison’s Disease. Some scholars now argue that this even put the country potentially at risk during major crises like the Cuban Missile Crisis, when tough, globally life and death decisions had to be made.

In fact, the real turn in public disclosure on health really only came during Lyndon Johnson’s tenure when he underwent surgery for the removal of his gall bladder. After initially trying to minimise the seriousness of this procedure, he took to showing the resulting abdominal scar to friends and visitors. Perhaps his growing fears about his falling credibility as a national leader due to the Vietnam War led him to go the full way and then some on his personal health issues. Thereafter, however, this set a bar that made it virtually impossible for the president, his medical caregivers or other officials to mislead seriously or dissemble about presidential health.

And so, as for South Africa, in this time of national concern, it is probably too late this time around for the Presidency to suddenly begin issuing detailed medical bulletins, and to bring a panel of medical specialists out each day to give clear, crisp and concise briefings to allay every concern. There has probably been a bit too much bad blood for that. Moreover, despite his series of medical emergencies, Nelson Mandela is obviously a very special case – especially since a national sense of wellbeing and national worth is so thoroughly intertwined with him personally and with his life’s achievements.

Nonetheless, this pushing and shoving between the media (both the foreign and domestic contingents) and the information gatekeepers about a leader’s medical circumstances should be brought to heel for the next time a senior official falters. For a start, when a future president has to speak on medical matters, it should be standard practice that he – or she – gets the best possible advice for explaining what must be said by the nation’s political leader.

Then, in addressing a president or other senior leader’s medical issues, it should be routine that a regular regimen of clear bulletins and straightforward medical briefings should be prescribed. This should be dispensed concurrently with a better diet of media understanding and appreciation that, going forward, the Presidency pledges to keep the country fully informed about the health of its leaders. DM

Read more:

- Different approaches to Mandela’s health (Anton Harber’s recent column on this issue, issued at his own website)

- To tell or not…disclosing candidate health issues at the National Public Radio website

- Reconsidering Ike’s Health and Legacy at the Eisenhower Institute of Gettysburg College website

- Deception, Disclosure and the Politics of Health at the Healthmedialab.com website

- ‘The President Is Ill’: How Health Has Impacted the U.S. Presidency at the Public Broadcast Service News hour website

- When Leaders Ail: Health Problems of Past Presidents and What They Tell Us at the ENT Today [the ear, nose and throat specialist] website

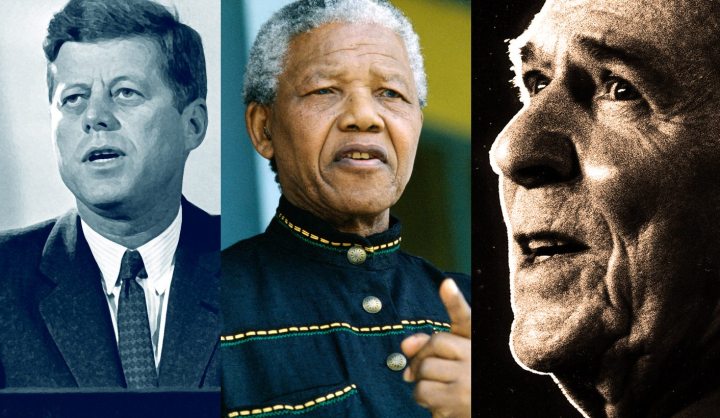

Photo: John Kennedy (Reuters), Nelson Mandela (Greg Marinovich), Ronald Reagan (Reuters)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider