World

When the air is the enemy

Recent news reports say the British and French governments have concluded that chemical analysis of samples obtained from Syrian sources confirm the use of sarin gas (a powerful nerve toxin agent) in the fighting in Syria. CBS News (as well as other media) reported, “France said Tuesday it has confirmed that the nerve gas sarin was used ‘multiple times and in a localized way’ in Syria, including at least once by the regime. It was the most specific claim by any Western power about chemical weapons attacks in the 27-month-old conflict. Britain later said that tests it conducted on samples taken from Syria also were positive for sarin.” This may – but only may – be the thing that changes the fundamental dimensions of the Syrian conflict. By J BROOKS SPECTOR.

The CBS report continued that “White House spokesman Jay Carney, speaking before the British announcement, said the French report is ‘entirely consistent’ with the Obama administration’s own findings, but added more work needs to be done to establish who is responsible for the use of the toxic substances and when they were used. ‘We need more information,’ he said.” The Russians, meanwhile, say they remain officially unconvinced of such allegations and their support for the Syrian regime remains as it was. As a result, despite these new claims about sarin usage inside Syria, at least at this point it remains unclear what specific tactical or strategic objectives the presumed users were attempting to achieve.

Nevertheless, this newest development has helped trigger various kinds of personal reminiscences on the part of some about gas in warfare; reminded us all of what we have read and know about the horrors of gas warfare from World War I up to our own time; and, finally, and most ominously, propels us onto a contemplation of what could yet happen in the Middle East if chemical weapons are truly unleashed in the civil war – or become distributed yet further.

As for those personal memories, inductees into national military service eventually had to confront what potentially was the most frightening drill of all for them pyschologically. It was much worse than all those live fire exercises, the long marches, or even those efforts to reassemble an M-16 rifle in the middle of the night in the dark – without leaving out the firing pin. This was the day recruits were herded into a lightless building, the doors were closed, there was a soft hissing sound, and then that sharp command, “Gas! Gas! Masks on! Move it, move it, soldier!”

Eyes began to burn, there was much rasping and coughing, and in the dark, soldiers furiously fumbled with that gas mask pack, tearing their fingernails on the clasps as they tried to get their slippery mask out of the bag and over the face. Recruits bumped into each other while drill instructors chivvied the laggards with, “move it ladies, move it!” just like the scene in films like Jarhead.

Now the gas in that room was only a strong dose of tear gas, maybe mixed with a bit of pepper gas – it certainly was not phosgene or mustard gas. It was about the same as the weapon of choice used on hundreds of college and university campuses, in city streets throughout the 1960s and into the 70s. But inside that gas-obscured, claustrophobic shed, with all those panicky trainees, the subconscious fears might just as easily have been channelling Wilfred Owen’s World War I battlefield dirge:

…Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling,

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime . . .

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs….

In one sense, of course, a death from gas warfare is no more brutal than any other death in battle. Dead is dead. But from the perspective of the struggling victim, it must be so much worse because it has turned the one thing everyone believes to be safe and free – the air – into an insidious killer. When the very air has become the enemy, it seems way beyond unfair; it is so much more horrific, random and capricious than any other kind of death.

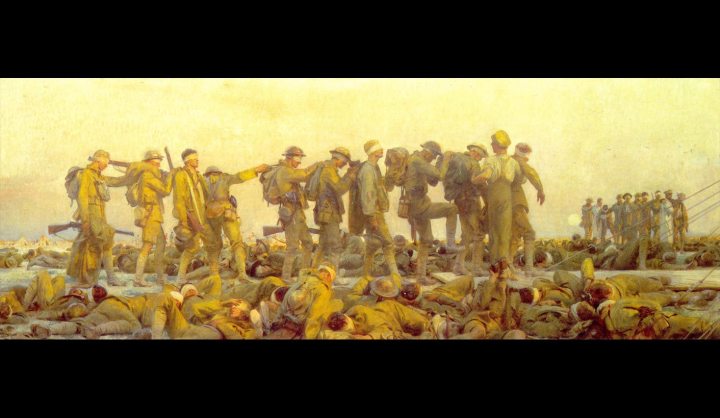

John Singer Sargent’s 1919 painting, Gassed, helped bring home the horror of gas warfare in World War I. In a broken, brown landscape, largely shaped out of the bodies of corpses, there is a group of 11 soldiers, each bandaged around the eyes, one leading the next as they trudge forward single file. Each has an outstretched hand on the shoulder of the man in front of him, as they struggle to reach a battlefield first aid station. A bleaker portrait of traumatic, useless death would be hard to find – and thousands upon thousands of British, French, German and other soldiers endured just such deaths and injuries to sight and lungs.

The experience of gas warfare was so heinous there was a global push to outlaw it entirely by treaty. Although the 1899 Hague Convention had already produced international agreement in which nations agreed “to abstain from the use of projectiles the sole objective of which is the diffusion of asphyxiating or deleterious gases,” this was a largely notional agreement signed prior to any major use of such weapons.

However, post-World War I, there was widespread public support globally for banning chemical warfare outright, resulting in the Geneva Protocol barring such weapons. In many ways, World War II marked a significant success in keeping chemical weapons off the battlefield – although not out of the death camps like Auschwitz, or in medical experiments on Chinese prisoners by Japanese guards. However, after the use of two atomic bombs to end World War II, arms control negotiators turned their attentions to develop regimens to limit the development and spread of nuclear weapons, given their obvious civilisation-ending, destructive capabilities.

But, then, after poison gas was used during a civil war in Yemen, after the US had used a range of defoliating agents in the Vietnam War, and then, most especially, following the use of chemical warfare in the Iraq-Iran War, world attention shifted back to attempting to keep the genie of chemical warfare under control. This culminated in the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention – a full-scale ban on the use, production and stockpiling of weapons that took force in 1997.

International concern about chemical weapons got another kick-start from the troubling saga of Shoko Asahara’s Aum Shin Rikyo religious cult in Japan that developed a stock of sarin gas it then deployed against its enemies and on the Tokyo subways in 1995 as a means of provoking mass terror in Japan. These attacks killed 13, injured hundreds more, and generated widespread fear about the group’s motives – and capabilities.

Photo: Former leader of Japanese doomsday cult Aum Shinri Kyo Shoko Asahara poses in this undated file photo. Asahara, whose real name is Chizuo Matsumoto, was found guilty of responsibility for the 1995 nerve gas attack that killed 12 and sickened thousands, and sentenced to death by a Tokyo court in February 2004. (Reuters)

A few years prior to the Aum Shin Rikyo events, Iraqi military use of chemical agents against Kurdish villagers in the Iraqi settlement of Halabj in the midst of the Iraqi-Iranian War, killed somewhere between five and ten thousand people. News of these attacks contributed to Western concerns about the deeper penetration of chemical (and biological) weapons (CBW) into the Middle East. Of course this event also triggered Western assertions that Iraq was well on the road towards the large-scale deployment of weapons of mass destruction – something that turned out to be a bit of wish fulfilling cover for the ill-fated invasion of Iraq in 2003.

However, since the Syrian uprising began, there have been growing worries about Syria’s possession of CBW capabilities – how much of it there was, what was going to happen to it as the regime faltered, who was going to use it, and against whom. As the civil war has grown in intensity and destructiveness, there has been growing concern these weaponised stockpiles of sarin and VX gases could be weapons of last resort – by Assad’s government and military, or perhaps by one or another of the rebel groups fighting for control. Alternatively, as the civil war moves towards some kind of end stage, whatever that might eventually look like, these chemical weapons might even be shopped or smuggled to other Middle East actors for their own ends – to states or radical non-state actors.

As a result, a key question is what will Syria’s neighbours – and their allies as well as Syria’s allies – do about such chemical weapons. Israel and Turkey may be the two neighbours most immediately and intimately concerned with this. Turkey is already hosting tens of thousands of Syrian refugees, has had occasional hostile fire along the border, and feels deeply concerned the possible collapse of the Syrian regime would send thousands of additional refugees fleeing northward – very possibly bringing weapons and sectarian fights with them into Turkish territory.

With Turkey’s own civil-military-religious conflicts becoming more prominent and potentially destabilising themselves, Turkish security officials must be increasingly concerned about these newest reports about Syrian chemical weapons use. A similar story has been playing out in Jordan as well, a country that has fewer resources to deal with the growing tide of Syrian refugees and much less of a sense of comprehensive nationhood.

Southward, the Israelis have been watching the civil war with growing concern as well, of course. In a recent column in the Jerusalem Post, Michael Widlanski, a former strategic affairs advisor in the Israeli Ministry of Public Security, is now advocating a more proactive approach to the Syrian crisis. As Widlanski argues, “Picking sides in Syria’s civil war is a bit like choosing between Hitler and Stalin. You do not like either side, do not want to deal with either side, but you have to choose anyway because, as they say, ‘it is what it is.’ ”

Widlanski then adds, “Today things in Syria are much worse than they were in 1979 [during another revolt]: more than 80,000 have died in warfare that began not long after the Obama administration reached out to engage the Assad regime, sending a US ambassador over the express and formal disapproval of Congress…. Hundreds of thousands of refugees have destabilised Jordan. Syria has already fired on Israeli positions, and Israel has already destroyed Syrian arms shipments to Hezbollah in Lebanon. Meanwhile, chemical weapons have been used, and the Russians are sending more advanced missiles to the Assad regime.”

Widlanski goes on to argue the Israeli government needs to hold its nose over the atrocities being committed on both sides and line up behind the lesser of the two evils to keep the whole country from falling apart completely. “Whatever the sins of Syrian dissidents, they do not match the half-century of blood spilled by the Assads. A second moral-strategic reason: Assad’s Alawites comprise a tiny part of Syria. The Alawites and other small groups deserve their rights, but the Sunni plurality has been waiting too long, and the Sunnis will eventually win.” Moreover, “Two of the worst terror forces in the world are backing Assad: Iran and Hezbollah. Bringing down Assad reduces Iran and Hezbollah.” So far, at least, the Israelis have held back, but if chemical weapons evolve into a weapon of choice for either or both sides and such weapons also begin to bleed across the border into Lebanon and into the hands of Hezbollah, well then that will be a very different set of circumstances for the Israelis to respond to as they will feel they must.

As for the major powers beyond the region, the Russians are clearly watching to see how they can continue to hold onto their Mediterranean naval base at Latakia, continue military sales to Syria, and thereby maintain a regional ally – even if it becomes a badly dented and shrunken one. But that also means being so positioned that – if necessary – they can jump ship on Bashir al-Assad.

As for the Americans, well their goals are to avoid more general warfare in the Middle East, somehow engineer a transition away from the Assad regime inside Syria, avoid the general collapse of authority in the country – and perhaps most important of all, prevent the diffusion of Syrian chemical weapons into the hands of radical non-state actors where controlling their use would become virtually impossible.

The real conundrum is how to get to some point beyond the civil war at present – especially since the warfare inside the country shows no sign of coming to an end; there is no real sense of momentum tipping the balance definitively one way or another; and, as each day passes, the humanitarian circumstances become ever worse inside the country and beyond. In such conditions, unless some kind of united international will can be imposed, will it really be such a great surprise if one side – or perhaps both – finally reaches for those tempting but terrible chemical weapons and then attempts to stage a 21st– century repeat of those World War I battlefronts of Ypres, the Somme and Verdun. And once such a thing comes to pass, what then for the onlookers? DM

Read more:

- France, Britain say sarin gas used in Syria at CBS News

- Britain finds evidence of sarin gas use in Syria at Reuters via the Jerusalem Post

- Our Syrian menu: Bad, worse, worst, a column by Michael Widlanski in the Jerusalem Post

- Suspect in ’95 Tokyo Attack Is Said to Be Caught at the New York Times

- Between the Covers (a review of Haruki Murakami’s book, “Underground”) at Jade Magazine

- Art from Different Fronts of World War One at the BBC

- List of chemical arms control agreements at Wikipedia

- War In The Gulf: Reporter’s Notebook; Poison Gas Attack: A Longstanding Fear That Continues to Nag the Troops at the New York Times

Main photo: John Singer Sargent’s 1919 painting, Gassed

Become an Insider

Become an Insider