South Africa

Analysis: When truth is the casualty, what is the cost?

The government’s bid to justify South Africa’s military misadventure in the Central African Republic was hardly Orwellian in elegance. However, stamped all over it was the blunt intent of Big Brother; so much so that it triggered some disturbing memories of a time when the US Army unflinchingly, even piously, declared: “We had to destroy the village in order to save it.” South Africa has some important lessons to learn, writes J BROOKS SPECTOR.

Whenever governments lie, dissemble or evade the obvious, it seems inevitable that writers will reach for their Orwell to clarify and make sense of what is true and important, and most especially his essay, “Politics and the English Language”. Immediately following World War II, and under the cumulative weight of the war’s horrors, plus Stalin’s purges, the early revelations of the Gulag Archipelago and still other terrible things on the way, Orwell had written eloquently from a position of undiluted anger at what had already happened – and what was clearly on the horizon.

In that famous 1946 essay Orwell had argued, “In our time, political speech and writing are largely the defense of the indefensible. Things like the continuance of British rule in India, the Russian purges and deportations, the dropping of the atom bombs on Japan, can indeed be defended, but only by arguments which are too brutal for most people to face, and which do not square with the professed aims of the political parties.”

And he had continued, “Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness. Defenseless villages are bombarded from the air, the inhabitants driven out into the countryside, the cattle machine-gunned, the huts set on fire with incendiary bullets: this is called pacification. Millions of peasants are robbed of their farms and sent trudging along the roads with no more than they can carry: this is called transfer of population or rectification of frontiers. People are imprisoned for years without trial, or shot in the back of the neck or sent to die of scurvy in Arctic lumber camps: this is called elimination of unreliable elements.”

The writhing to justify South Africa’s military misadventure in the Central African Republic, until the government’s most recent decision to cut its losses and withdraw before being sucked in deeper still, triggered some uncomfortable memories of another time. Like many who came of age during the Vietnam War, the thrust of Orwell’s essay, with its disgust over government prevarication and obfuscation, came to have particular relevance to that contentious time as well. America’s early, limited involvement in Vietnam’s conflict began after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu and the 1954 partition of Vietnam.

Soon the US had dispatched a small contingent of military trainers and advisors to South Vietnam. By the end of the Kennedy administration and its revived focus on counterinsurgency warfare and a pro-active defence of American positions around the world, there were more than 10,000 military personnel in Vietnam. At that point, however, they were still mostly serving in advisory, training and support capacities rather than as active combat soldiers.

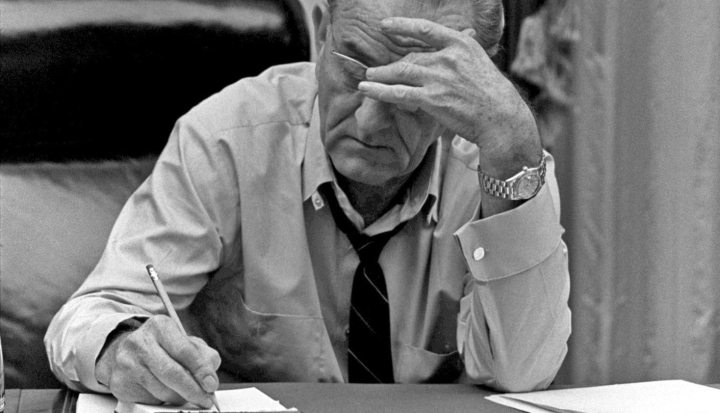

When Lyndon Johnson succeeded Kennedy on 22 November 1963, there was still little planning for a major increase in a US military commitment in Vietnam. But there was also that fact of a 1964 presidential election pitting Johnson against a vigorous right-wing conservative Republican, Senator Barry Goldwater. Johnson had famously declared he was not about to be the first American president to lose a war.

Moreover, Johnson was facing an opponent whose hawkish views on opposition to communist expansion during the height of the Cold War would be a challenge with many voting constituencies. Together, these facts effectively levered Johnson into a mindset of looking for a way to demonstrate strength, resoluteness and military fortitude, even if he always insisted his first focus was to concentrate on the economy, reduce poverty and lock down the legislative basis of the civil rights revolution.

Providentially it seemed, on 2 August 1964, US Navy destroyers were engaged in routine reconnaissance and surveillance patrols in the waters of the Gulf of Tonkin, international waters but near to North Vietnam. On that night, the USS Maddox and support aircraft engaged several North Vietnamese patrol craft, inflicting damage on them while receiving incoming fire as well.

Then, just two nights later, the Maddox and a second destroyer, the USS Turner Joy, reported a second round of unprovoked attacks. These reports fed outrage on the part of many in America and led to calls for a serious response to these North Vietnamese attacks. (Subsequent careful examinations of the communications and signals records for both ships have cast great doubt on the claims that there ever even was a second attack, but the psychological effect was achieved.)

The climate of the times for Americans was one which had recently seen the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Berlin Wall and much more – all seeming to be challenges to American resolve. It was easy to take the view that here was where it was necessary to draw a real line in the metaphorical sand. And so, in the wake of those initial, alarming reports about attacks by North Vietnamese patrol boats on American naval units – and egged on by the hubris of many in the Johnson administration which seemed eager to make a firm stand on national strength of purpose – the Senate moved quickly.

Just three days after that now-discredited second attack, the Senate passed its Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, a vote that authorised the full use of America’s conventional military forces in Southeast Asia. Rather than moving on to a formal declaration of war, and without a thorough evaluation of the implications of this open-ended commitment, this one vote in the Senate became the basic legislative justification for the calamity that unfolded over the next decade.

In the years that followed, through the wreckage of two presidencies, there was one false prediction after another that just one more escalation of military strength would be the turning point for American fortunes in Southeast Asia, even as the US became yoked to an unsavoury ally that to far too many people seemed little different from – or even worse – than the enemy the nation was supposed to be opposing.

As the untruths continued, opposition to the war grew, half a million American troops were sent off to “The Big Muddy”, the military service draft hauled in millions for increasingly reluctant service, and succeeding presidents and other officials accused students and other dissidents of inciting disloyalty – or worse. This climate led directly to domestic spying on American war opponents, the Watergate scandal that stemmed from that psychosis and then, ultimately, Richard Nixon’s forced resignation as president.

Before Vietnam, for most Americans, there was a broad national consensus that the government largely acted in the best interests of its citizenry. By the time the American involvement in Southeast Asian warfare had lurched to its unhappy conclusion, by a sizable majority, trust in government’s most basic actions had largely evaporated. For far too many people, the very Orwellian phrase, “We had to destroy the village in order to save it” had come to be the embodiment of the government’s heedless way with the truth. This acrid relationship between citizens and their government continues to this day in many ways, for many people.

While South Africa’s intervention in the Central African Republic never reached Vietnam’s military extent or its effect on American individuals and institutions (or, for that matter, the impact of the lies and dissembling of the old South African regime in its description of its wide-scale attack on Angola as merely fighting “at the border”), there were disturbing echoes of those conflicts.

Important lessons must be drawn from this misadventure if even worse is to be avoided. The dissembling on what missions, exactly, South Africa’s troops were carrying out in the CAR; who, precisely, they were fighting, and on behalf of what objectives – and for whom – they were fighting remains deeply troubling. There was little in place to stop the onward rush to disaster except growing public criticism. Even worse, the foundation for this intervention – a secret, unseen memorandum of understanding signed some six years ago – allowed South Africa’s leaders to assert anyone challenging the government’s justifications or calling for a more thorough examination of this commitment – here again as with America’s Vietnam experience – verged on disloyalty.

As these words are being written, it seems that the Zuma government has – under pressure – decided its CAR misadventures were loss leaders whose cost in lives, treasure and national reputation were more than any potential commercial benefit that might accrue to its shadowy beneficiaries. As the country’s international relations minister told the press on Thursday, quoting Jacob Zuma, “Since the self-appointed leader of the CAR took over, in the process nullifying the Constitution, the Parliament and the Judiciary, it has become clear that the Government that we entered into an agreement with was no longer in place.”

Even so, there are reports that South African military forces remain in stand-by positions in a nearby nation, available for another, later run at national military hubris. The ongoing justification for such ideas seems to be that any rebellions against sitting African presidents can no longer be tolerated and must be resisted by other African leaders and their military forces. If followed to its logical conclusion, such a position could still open the door for future baleful choices that could commit the SANDF to other follies.

Back in 1964, for a generation of American leaders, it was an article of faith that no more territory would be ceded to the Sino-Soviet bloc and its satellites – that the advance would be stopped at the DMZ separating North and South Vietnam. And the result – ignoring a century of history about the nature of guerilla insurgencies and the need to ensure that in a territory like South Vietnam it was crucial its population was also invested in its government – became a terrible, costly lesson for Americans.

If South Africa had continued to invest its reputation and treasure to undo what had occurred in the CAR, would there have been any reason to assume the result would have been any more fortunate for South Africa, its leaders, its government, its military or its international reputation than America’s decade of fighting in Vietnam ultimately proved to be for that nation? If there had ever been such a justification, this country has yet to hear it from its leaders. DM

Photo: President Lyndon B. Johnson in an undated photo courtesy of the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library & Museum. REUTERS/Lyndon Baines Johnson Library & Museum/Handout

Become an Insider

Become an Insider