South Africa

The TRC’s unfinished business: Old wounds, new oppressor

The death of Apartheid assassin Dirk Coetzee and exhumations of two bodies, believed to be those of missing Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK) activists, have reopened the old wounds of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s unfinished business. It has also prompted questions again about why the ANC government has been so contemptuous of victims of Apartheid and why the state has also not bothered to prosecute those denied amnesty by the TRC. Perhaps most bizarre is why government wanted (and still wants) to introduce a new special pardons process for politically motivated crimes, something which would completely undermine the work of the TRC. By RANJENI MUNUSAMY.

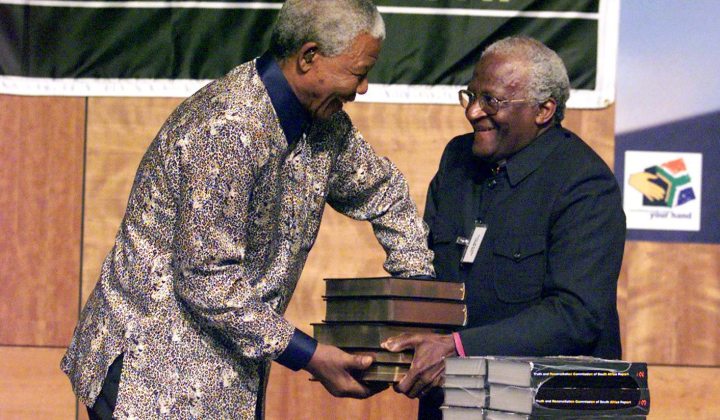

Ten years ago, on Human Rights Day 2003, the president, Thabo Mbeki, was handed the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) by Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The TRC report documented some of the most painful chapters of South Africa’s past, and recorded the public process to heal some of the wounds of those who suffered, who lost loved ones and who search for answers.

The TRC report is by no means a comprehensive record of Apartheid crimes and confessions, but it chronicles the journey and findings of the process to uncover some of the truths about atrocities committed across the political spectrum. It is a picture of the horror of our past, but also a source of pride: in a nation able to tell its painful story, and build a future free from retribution.

But there is still a lot of bitterness, pain and anger. The South African government has largely ignored the TRC’s recommendations in the final report on reparations and rehabilitations. Apart from a nominal R30,000 paid to about 17,000 victims, the state has ignored appeals for proper reparations.

To add insult to injury, it has emerged that government wants to use funds earmarked for the compensation of Apartheid-era victims to renovate municipal infrastructure.

According to the Sunday Times, the Department of Justice’s TRC unit wants to divert R500 million of the R1.1 billion in the President’s Fund, which includes donations from foreign governments for victims of Apartheid crimes, to municipalities to renovate the crumbling infrastructure around the country. The Khulumani Support Group, an organisation representing the survivors and victims of human rights abuses during Apartheid, says this constitutes a further injustice to the victims.

“This is happening despite thousands of interventions made by victims themselves to ensure access to appropriate and effective remedies. It remains inconceivable that a justice ministry could preside over implementing proposals characterised by such callous disregard for human suffering, particularly in the month dedicated to human rights in South Africa.

“Ten years on and 20 years into democracy, the state has not yet taken the views and submissions of victims seriously. Thousands of appeals have been lodged to date by Apartheid victims with the Presidential Hotline to no avail despite the contributions of those who were violated in the quest to bring a new government to power. They will never forget the extent of this failure,” Khulumani said in a statement.

The South African Coalition for Transitional Justice has instructed lawyers to assess the legality of this action, Khulumani said, also noting that countries that have drawn inspiration from the example of the South African transition are dismayed by these developments.

The contempt shown to the victims of Apartheid are indeed perplexing, particularly since most would have been members and supporters of the ANC. While the ruling party has set up an investment arm for its own benefit, it has done no such thing for those whose blood, sweat and tears it took to win state power.

The state has also shown very little willingness to pursue cases emanating from the TRC process. When the amnesty process was complete, the commission handed over a list of 300 names to the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) for investigation and prosecution.

The NPA established the Priority Crimes Litigation Unit (PCLU) to pursue these matters but, according to Howard Varney, senior programme advisor at the International Center for Transitional Justice, the unit was “rendered impotent” by the failure of the state to assign it investigators or to compel the police to provide investigation officers. Varney said less than a handful of prosecutions were taken forward.

The unit’s only successful case has been a plea bargain agreement with Apartheid law and order minister Adriaan Vlok, police chief Johan van der Merwe and three other police officers for the attempted murder of former presidency director-general Reverend Frank Chikane. The matter was steeped in controversy, as all the accused received suspended sentences and were not required to disclose information on hit lists and hit squads that could have been used against other senior security officers.

The PCLU has been in the news recently as a missing persons task team working under it was responsible for the exhumations of two bodies at Avalon Cemetery in Soweto, believed to be the remains of Umkhonto we Sizwe activists Corlett “Lolo” Sono and Siboniso Tshabalala who disappeared in 1988. The two were last seen alive at Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s house in Soweto and the TRC found that she was involved in Sono’s abduction by the Mandela United Football Club. The remains are undergoing forensic tests to confirm the identities.

The PLCU had also been working with Apartheid death squad commander Dirk Coetzee to identify burial sites of missing activists. Coetzee died earlier this month before he could point out the grave of Sizwe Kondile, whose body Coetzee and his cohorts burnt while they had a braai nearby.

The TRC granted Coetzee amnesty, a move that angered the families and friends of his victims, who said Coetzee’s revelations had failed to bring closure to deaths of their loved ones because he had not fully disclosed all the information he had about their.

And if the controversy sparked by the TRC’s amnesty process is any yardstick, the government’s plan to open a special pardons process for political crimes will cause outrage if it goes ahead.

In 2007, former president Thabo Mbeki created the special dispensation process to deal with pardon applications from people convicted for offences they claimed were politically motivated, but who did not participate in the TRC. About 2,000 convicted persons applied for pardon under this special process. Vlok, Van der Merwe and several far-right prisoners convicted of racially motivated crimes were recommended for pardon by the political party reference group processing the applications.

The reference group repeatedly refused to allow victim input also declined to disclose its recommendations to the president. When Kgalema Motlanthe was acting president, he also refused victim input or to lift the blanket of secrecy under which the pardons process had been conducted. A coalition of civil society organisations applied to the Pretoria High Court to restrain the president from issuing pardons under the special dispensation.

In April 2009, the North Gauteng High Court issued an interim order restraining the president from granting any pardons under the Special Dispensation for Political Pardons. Bizarrely, President Jacob Zuma then joined members of the AWB, perpetrators of brutal race crimes, in an appeal to the Constitutional Court, which ruled in February 2010 that the decision to exclude the victims from participating in the special dispensation process was irrational and contrary to the rule of law.

But the matter is still not off the table and, for some inexplicable reason there is still reluctance to consult the victims. Last April, an NGO coalition sent Zuma a warning letter with comprehensive documentation setting out their objections to the special pardons process. In a memorandum attached to the letter, the South African Coalition for Transitional Justice says that central to the TRC’s amnesty process was the requirement of full disclosure. However, under the special pardons process, applicants were not required to make full disclosure.

The memorandum states that the reference group which processed the special pardon applications divided them into offences before 1994 and political offences post 1994. The post 1994 category includes taxi violence, stock theft, “repossession, arms acquisition and fundraising” and farm attacks.

The coalition points out to Zuma in the memorandum: “The political objective requirement of the TRC process related to those offences aimed at overthrowing the Apartheid order and those offences committed to resist such actions. It was not open to amnesty applicants to put up any and all political objectives.”

The coalition asks Zuma in the letter to provide any information he has on the granting of special pardons so that it can make representations. It also asks that Zuma or his legal representatives provide an undertaking that the president will not issue any pardons under the special dispensation until all the issues raised by the coalition have been resolved.

The matter is probably still sitting in Zuma’s overflowing in-tray as there has been no substantive response since then. However, the danger of special pardons being introduced has still not been removed.

The underlying reason for the special pardons process, as well as why the ANC has been treating the victims of Apartheid with such disdain, is difficult to fathom.

Why will it not compensate victims – to the extent that it would rather redirect money for reparations to the renovation of municipal infrastructure?

Why can’t it prosecute those who could not be bothered to tell the TRC the truth about their horrendous actions?

Why can’t it dedicate resources to finding those missing for decades, and put their families out of their pain and misery?

And why does it want an opaque pardon process, which has dubious criteria for amnesty and no victim participation?

The ANC cannot continue to trade on its struggle credentials while it becomes the new oppressor, tormenting, or at the very least forgetting, those who have already suffered for its cause.

Is this the ultimate example of how the ANC eats its own? It is morally not right, legally wrong and very, very bad politics. The well of goodwill from which the ANC has been thirstily drinking for almost two decades now may be deep, but infinite it is not. The rulers of South Africa might want to think about that. DM

Photo: Chairman of the TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission) Archbishop Desmond Tutu (R) hands over the TRC report to South Africa’s President Nelson Mandela at the State theater Building in Pretoria October 29. (Reuters)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider