World

Dalai Lama: I would love to see Mandela once more

Having been witness to a tragedy that has unfolded over five decades, with no sign of reprieve from the Chinese, the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader, His Holiness the Dalai Lama, brings a hard-won sense of compassionate pragmatism to his worldview. And if South Africa has the confidence to negotiate a “Middle Way” with trading partner China, and if there is no risk of it being embarrassed (or even inconvenienced), the Dalai Lama will be “very happy” to visit again. And pay his respects to Nelson Mandela. It’s really that simple, writes GUY LIEBERMAN.

The Himalayan hill town of Dharamsala starts in the plains and rises up to the snowline of the towering Dhauladar range, with the village of McLeod Ganj perched on a narrow ridge somewhere in between. With commanding views of the mountain peaks and terraced valleys, this is the refuge of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, home of the Tibetan government-in-exile and was, from the mid- to late 90s, my home too.

The refugee settlement, a hodgepodge of colourful, shabby buildings that ascend the forested foothills, serves as a safe haven for Tibetan exiles, many of them escapees or victims of Chinese imprisonment and torture; many of them orphaned. Stories too numerous tell of children having to boil and eat their shoes to stay alive while lumbering over the high altitude passes that take them from Tibet, into Nepal, and eventually to Himachal Pradesh, the North Indian state where the Dalai Lama and Dharamsala receives those who have survived.

It is a tragedy that has unfolded over five decades, with no sign of reprieve from the Chinese.

The Tibetans in McLeod Ganj work and live among Kashmiri shopkeepers, local Himachali Indians and an array of Westerners – Buddhists, activists, spiritual adventurers, partiers – many of whom have found one or more reason to be happy either visiting Dharamsala for a few weeks or staying on long term. I first arrived in 1994, a 23-year-old hippy, high on the fresh hopes of a new South Africa. My entry into the world of expatriated Tibet was a turning point for me. I stepped, unknowingly at first, into the initiation of a new path: one of an activist. Granted, I was a little slow on the uptake – my mates back home were in celebration, all our exiled heroes were already returned and jostling for government positions – while I was hitting the lows of a parallel political battle that had, and still has, no end in sight.

When the first Tibetan self-immolation took place in Delhi, I witnessed the stunned silence of Dharamsala, followed swiftly by the fire of impotent rage that set the community on edge. The inverse act of a suicide bomber, a man had doused himself in petrol and set himself ablaze to draw the eyes of the world to one of the most painful – and unnecessary – liberation struggles on the planet.

My activism led me into several years of full-time involvement in the Tibetan cause, including the three eventful visits of the Dalai Lama to South Africa, in 1996, 1999 and 2004. As local liaison for these trips, and during my time in Dharamsala, I was privileged to meet several times with the man who has led the Tibetan nation through the darkest period in its history.

Fast-forward 19 years and more than 100 self-immolations, and I’m back in McLeod Ganj, this time with my Blackberry and MacBook Pro, enjoying super fast wi-fi and mouthwatering Tibetan veggie momos for breakfast, lunch and dinner. I marvel at how things have changed – and yet realise how so much has stayed the same.

Photo: Dharamsala under the full moon (Michael Foley)

I’ve returned to Dharamsala to once again meet with the Dalai Lama, mainly to hear his thoughts about his last two attempts to visit the country and being rejected by the South African government, and how he feels we should proceed. We meet in the same place we have over the years, a simple, comfortable sitting room on the property of his temple complex, which also houses his home and private office.

“Firstly”, he leans closely over to me, to be sure that I understand what he is saying, “it is important to not cause any embarrassment. If for some reason the South African government feels uncomfortable with my visit, then okay. If, however, it doesn’t cause too much inconvenience, then I would be very happy to come. Very happy.”

How would he advise South Africa to deal with China’s growing influence both here and on the continent, considering that it directly affects his access to the country. “Africa needs to stand firm with China – to view themselves as equal, not beneath them. The Africans can learn much from China’s approach to work, they are very industrious. They can be good partners.” He understands that China needs Africa as much as Africa needs China. The truth is that I’ve found the Dalai Lama often far more pragmatic than the emotional activists who want to push China’s influence back. He navigates with a sense of compassionate practicality.

His approach has always been to engage China, bring it into the family of nations, gain real trust on all sides, then if any change needs to happen, that will be the time. Isolating China, he feels, is a useless and impossible pursuit. It’s the same policy he has held on the issue regarding China’s control of Tibet. His Middle-Way Approach, the government-in-exile’s official position on China (by democratic vote, not decree), states clearly that what the Tibetans want is genuine cultural autonomy, while staying within China’s borders. If the Chinese leadership could hear this, without the consistent fear of a later attempt at independence, it could serve as the greatest PR exercise the People’s Republic would ever take on – especially while this current, and much loved 14th Dalai Lama is still alive.

Photo: A monk points to a picture from a book of the Dalai Lama (R) beside Choekyi Gyaltsen, the 10th Panchen Lama (2nd L), at a Tibetan house in Labrang Monastery during the Tibetan new year, in Xiahe county, Gansu Province, February 11, 2013. REUTERS/Carlos Barria

In the eyes of the Chinese, however, if they give Tibet this opportunity – not that they recognise any political justification for it – then attempts at secession would set in like rot within the motherland. Just like the Tibetans, other smaller ethnic groups that the Han Chinese have forcefully absorbed into One China over the centuries would want their own form of official identity too. This is not in China’s game plan –which means that Tibet remains under a firm and brutal fist. With no relenting on China’s part, the only way a society that is formed on non-violence can respond is this continued macabre expression of protest: self-immolation.

The Dalai Lama is the most significant person I’ve met. When in conversation with him, you realise how rare it is to be in the presence of someone who is completely engaged with the one in front of him – totally undistracted and with an exceptional clarity of mind. Because of his mastery as a Buddhist meditator, his daily contemplations on impermanence and the inevitability of change seems to have drawn him deeply into the moment, awake and illuminated. There is no rote, no tedium, nowhere else to be.

Still, I want to drill down further into his experience regarding South Africa –does the Buddha of Compassion get hurt feelings?

The 2011 visa debacle was managed with an undeniable cowardice by our government. In the end, there was never an official “no”, just a repetitive bleating that “it’s still in process”, for months up until the day before the intended visit. By that time, the Dalai Lama himself had to step forward and inform his hosts that there was no realistic way the trip could happen – which gave our leadership the opportunity to say, “ah, well, there you go, he cancelled the trip.”

So in this context, I find it ironic that the Dalai Lama would concern himself with the dignity of the South African government, with little concern for his own humiliation. This is the gauge of his wisdom and spiritual maturity. He is, somehow, beyond the battles and fears and pride that steer society. But the irony continues; why is our government not allowing the Dalai Lama entry into South Africa? Because China has bought us, including our foreign policy. What is China’s position on the state of South Africa’s dignity? There is no position.

We effectively help shackle and silence those who call for freedom, in the name of the very same form of oppression this country suffered for decades. Our liberation narrative has transformed itself into a chilling parable. Why does the irony seem totally lost on our leaders? Where is our honesty, our courage? Has everyone left the house that Luthuli built?

I reflect for the Dalai Lama that the first time we met in this room 18 years ago, I was an amped up but naïve activist, convinced that then president Nelson Mandela and the South African government would come to Tibet’s aid. It seemed such an obvious political segue. The empathy linkages were clear, and the timing was perfect. South Africa’s recent treatment of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan situation has been more than a disappointment, it’s been shameful – our leadership needs to look closely at itself and acknowledge complicity.

The last time I saw the Tibetan leader in South Africa was on the eve of his departure in 2004. We had had an outstanding trip, and were preparing for the last few engagements of the day. Mandela sent word through to us that he wished to meet with the Dalai Lama before he left the country. After their meeting, I approached Madiba to greet and thank him, and when I turned to leave I saw that the entourage had left the room, leaving just the Dalai Lama standing there. He was looking over at Mandela, so I stepped aside to witness this extraordinary moment.

Now, here in his home, I had the opportunity to share with the Dalai Lama what I had honestly thought to myself was likely the last time these two giants would see one another in this lifetime. As the thought passed, the Dalai Lama lifted up his hand in a gesture and said to Mandela, “See you again! I’ll see you again.”

Does he wonder if he’ll ever meet with Madiba? “Of course, I hope to meet with him again.” He lifts his hands slowly in prayer to his forehead. “I would like very much… to pay my respects to Nelson Mandela.” Then he sits, quietly, looking into middle space. Silence fills the room. He’s thinking about the question, and all the factors that constellate around it, this is clear. His reverie is profound and still, and one begins to sense the level of depth this man operates at. He sighs and returns his attention to our conversation.

I bring it around to this: will the Dalai Lama once again accept the many invitations to South Africa that have been extended to him by universities, institutions and individuals here in South Africa? His response is direct. “Yes, certainly.”

The loudest champion for his visit to South Africa is clearly Desmond Tutu, who publicly flayed the government for not allowing his fellow Nobel laureate and very close friend to attend his 80th birthday celebrations in Cape Town in October of 2011. In his fury, he even promised at the time to pray for the ANC’s demise – which, interestingly, is a totally foreign sentiment to the Tibetans.

His Holiness always warms when he speaks of Tutu. “I am still very keen to visit my friend Archbishop Desmond Tutu at his home. Whenever there is a gathering of Nobel peace laureates, he is always the most jovial one, always laughing, always happy.” At this he chuckles deeply, shaking his head. When the two of them get together they are like mischievous children. It’s no wonder Tutu expressed such heated outrage at the denial of the Dalai Lama’s entry into South Africa – without an overlord (besides the Trinity), he has no-one defining for him how he has to behave, or whom he can and can’t befriend. The blatant incongruity here is not lost on him.

In South Africa the Dalai Lama has had an effect on many who have met him, sometimes on people one would least expect. Among his most memorable experiences were his visits to Soweto. In 1996 I witnessed a spontaneous exchange with a family in a suburb there. We had just met with Walter Sisulu at his home, and were about to move on toward the next appointment, when the Dalai Lama asked if he could meet some local people – perhaps those who didn’t know who he was. He wanted a direct experience with some residents from the neighbourhood. So the entourage drove around and decided on a street that the VIP state security team (whose members don’t appreciate surprises like this from their VIPs) decided was easy enough to secure. The local representative from the Department of Home Affairs who was travelling with us knocked on a door, and the Dalai Lama was welcomed into a small home. There he met a family with a few children and through tea and conversation, a connection was made.

On his return to Joburg in 2004, he asked if it was possible to meet that family again in Soweto, so he could check in on them. The son, then a child and now 17, was asked by the Dalai Lama what he was doing at the time, and the lad told him he was completing matric. What were his plans afterwards? He hoped to study, but it looked like he would have to find a job – the family did not have the means to send him on to further education. The Dalai Lama then made a commitment to the young man to put him through university, which he did. It was a small, personal act, not broadcast on any platform or in the media (until now, and that’s my call), but it spoke to his way in the world. Of course, the life of the young man, who’s now working at a bank, was altered dramatically – not just upon being granted a university education, but having met this unknown, holy uncle from another continent, who clearly saw something in him.

Photo: Guy Lieberman and His Holiness the Dalai Lama, in Dharamsala, late February 2013.

The Dalai Lama shared his thoughts on Africa in the context of the current state of the world. “I always consider Africa a huge continent, not only physically, but huge with potential. I think the world is passing through a critical phase. We need to find our common interest, our global interest. If there is a general happiness in the world, and there are no serious problems, then okay, some small fighting here and there, that is to be expected. But if the whole world is fighting…! Then this is critical.”

He sees Africa’s potential as a player in bringing the world to some form of equitability, as a vast middle ground, a place of common global interest. If we could genuinely experience ourselves in this light, and reciprocate his view, we might begin to feel large enough for the simple act of letting a man of his stature into the country.

Does he feel if there is one essential ingredient missing for Africa to stand up and play its role in the future of the world? His answer, more as a kindness than a criticism, says everything: “Africa just needs to find confidence in itself.” DM

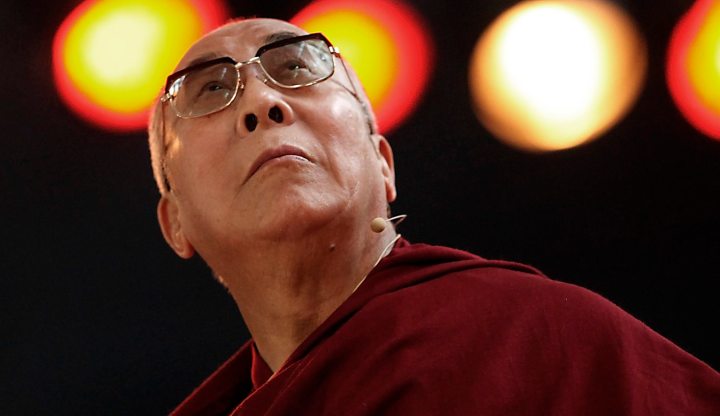

Main photo: Tibet’s exiled spiritual leader the Dalai Lama attends a conference called “Living Together with Responsibility and Cooperation” in Sao Paulo September 17, 2011. REUTERS/Nacho Doce

Become an Insider

Become an Insider