Maverick Life

Amina Cachalia: The poetry of her hope and history

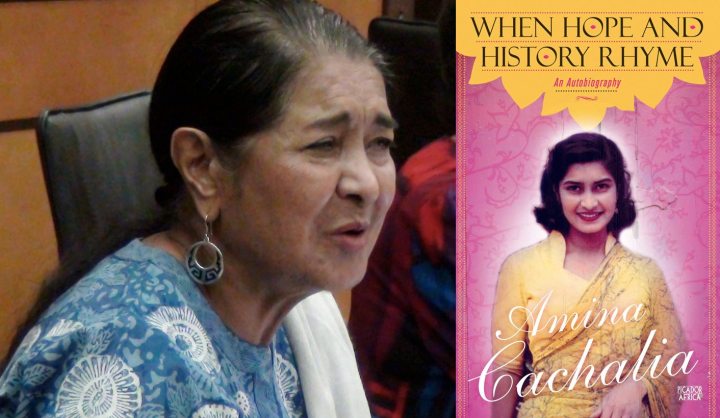

Amina Cachalia, the diminutive feminist and icon of democracy, died just 37 days before the launch of her autobiography. KATHY BERMAN read the book, and pays tribute.

One can’t help but wonder what kind of event Amina Cachalia – beautiful, gracious and feisty struggle stalwart – would have envisaged for the launch of her autobiography, When Hope and History Rhyme. Who would Cachalia have cajoled to join her on the podium? What would they have said?

The salient question, of course, is also what Cachalia herself would have spoken about. The Past? (“There were anecdotes and memories that flooded my mind, some of which I had written down and were strewn all over my desk and elsewhere.”) The present – potentially less perfect than what she had fought for? (“What I am living through now in the early years of the twenty first century is the golden age that Nelson Mandela mentioned in one of his letters to me. He had been dreaming about this all of his life… Are we living in the golden age? I certainly hope so, although it doesn’t always feel like it…”)

Or a more golden future?

Sadly, we will never know. For the book launch of the diminutive icon of democracy and the democratic struggle for women’s rights, coincided with her memorial: Amina Cachalia died, unexpectedly, 37 days before the launch of her autobiography – at the age of 83. She never saw a printed copy of the book. And so one can only speculate that the book launch would have been perfectly orchestrated: elegant, honest, and memorable.

As things stand, the event occurred in its place was just that. The memorial/ book launch for Cachalia was held on Saturday 9 March at the Wits Great Hall, where, ten years ago, she had been accorded an honorary doctorate in law for her contribution to the struggle for social justice and human rights.

Coming as it did, on the heels of some of our most distressingly and inexplicably violent months, it was fitting that the memorial was timed for the day following International Women’s Day.

Attended by so many members of the ‘golden generation’ of struggle stalwarts – all intimately referenced in the autobiography – it was a moving reminder of the true sacrifices of the founding mothers and fathers of our democratic country… and, sadly, the massive imperfections of our almost two-decade old democracy.

Amina Cachalia was born Amina Asvat on 28 June 1930, the ninth of eleven children of activist Ebrahim Asvat and Fatima (Essack) Asvat. Beset with a heart condition that threatened to end her life prematurely, the diminutive Cachalia had a feisty spirit that would not be beaten. From an early age, as her family moved from Vereeniging to Newclare to Fordsburg and surrounds, she committed herself to the struggle for human rights and gender equality – in her immediate, and broader, South African community. At the age of 18, she formed the Women’s Progressive Union, and went on to make her mark on, and participate in, nearly every one of the landmark events that marked the Struggle for democracy during the latter half of the twentieth century.

Fortunately for us, she has immortalised this in print: “One day I realised it was time to go beyond dwelling on the past, which I did from time to time in a few stolen moments, and jotting down notes here and there, and get down to serious business. I wanted my grandchildren and their children to know their roots, and I wanted to travel back as far as I could remember in order to record my extraordinary journey.” And boy, can she remember – in exquisite detail.

Cachalia’s autobiography tells the tale from inside, in vivid, delineated precision, relating not only each and every one of the momentous moments in the “long march to democracy” – but the motivations, decisions and emotional nexuses that governed each and every historical event. “There were times when I carried an adventurous spirit within me, there were times of pain, there were times of joy, and, at other times, a great sadness engulfed me,” she writes.

Amina Asvat married Yusuf Cachalia when she was 25, in 1955. They had two children, Ghaleb and Coco, and she and Yusuf enjoyed forty happy years together – under the most trying circumstances, as the Apartheid regime meted out one calculated and inhumane challenge after another against them and their cadres. Yusuf died in 1995, on the eve of the first anniversary of our democracy. Cachalia was to continue with her commitment to justice and democracy to her death. Among other awards, Cachalia was accorded the Order of Luthuli in 2004 for her “lifelong contribution to the struggle for gender equality, non-racialism and a free and democratic South Africa”.

Nadine Gordimer heralds her friend in the Foreword: “Of all Amina Cachalia’s distinctions and achievements, the greatest is her identity, lifelong, active in past and present, as a freedom fighter, now needed as much, believe me, in the aftermath of freedom as in the struggle”.

Both Cachalia and her husband were born into activist homes and were destined to make their marks on our collective history. Cachalia describes her heritage: “My father was a very learned and well-read man, and I always remember him saying earnestly, ‘If you don’t resist injustice it’s like death’. Their lineage was illustrious: “My father and Gandhi were close colleagues in the struggle but Ahmed Cachalia [Yusuf’s father] was Gandhi’s most beloved right-hand man.” She appends a quiet rider to this: “Gandhi left South Africa in 1914, and some years later, I would marry the son of his right-hand man. “

And so the tale unfolds, including her involvement in the Passive Resistance Campaign in the 1940s, and the Defiance Campaign of the 1950s – which led to her incarceration in 1952. It was on 9 August 1956 (now commemorated in South Africa as Women’s Day) that Cachalia, along with the other icons of the women’s struggle, Helen Joseph, Lilian Ngoyi, Albertina Sisulu and others marched on the Union Buildings in Pretoria with 20,000 women in protest against the proposed amendments to the Urban Areas Act of 1950 – colloquially the heinous “pass laws.” That day was marked by the phrase that has resonated across – and beyond – Anti-Apartheid history: Wathint’Abafazi Wathint’imbokodo: ‘Strijdom, you strike the women, you strike a rock.’

Cachalia went on to be banned in 1963 for 15 years, while Yusuf was placed under house arrest and banned for a total of 27 years. The book describes in precise detail not only the “myriad and momentous occasions that are part of the tapestry” of her own life – including the decision to send their children, Ghaleb and Coco, to be educated in exile in the UK – but also the myriad and momentous events that led to the freedom of this country – in precise and, at times, disturbingly intimate, detail. The book’s pages drip with icons of the struggle who are today still revered as heroes of our liberation – for Cachalia, all comrades, friends, intimates. And, in her compassionate honesty, revealed also as real, flawed people. Cachalia doesn’t shy away from describing these flaws in her gentle and genteel – but uncompromisingly honest – manner.

And it is this sense – of gentility, compassion and honesty – that translated into the memorial itself. The memorial was addressed by her four grandchildren, Luiza, Chiara, Tariq and Yusuf; her children, Ghaleb and Coco, and Wits Politics Professor Shireen Hassim, with contributions from her sister and nephew from the UK.

A rousing, erudite and elegant opening address by Deputy President Kgalema Motlanthe positioned Cachalia clearly in the firmament of our historical icons: “A product of her times, Amina Cachalia comes from a ‘golden generation’ in the annals of both the anti-colonial and anti-Apartheid history: Invoking Amina Cachalia’s name necessarily brings to mind such glorious names as Yusuf Cachalia, Fatima Meer, Yusuf Dadoo, M.G. Naicker, Helen Joseph, Lillian Ngoyi, Rahima Moosa, Sophie de Bruyn, Ruth First, Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Joe Slovo and many others.”

And with this came some disjuncture. For while on the one hand, the Great Hall was filled with the [now aging] familiar faces of the [then Transvaal] UDF of the 1980s, and the remaining ‘golden generation’ of heroic democrats, it was the reference to the post-Apartheid political mandate – couched in political rhetoric – that jarred somewhat. No, not that the speech wasn’t beautifully penned, elegant and poised. Just that it spoke of a South Africa that we haven’t quite realised – which the Deputy President acknowledged – but for which, it must be said, Motlanthe and his cohorts in government have to take responsibility.

One can’t but help but wonder whether the Deputy President was somewhat discomfited by the frank critiques of our current democracy, framed as they were through Cachalia’s eyes – as an impeccably committed, loyal life member of the ANC, but as one who saw her loyalty translating into honest critique.

For time has moved on from these [oddly halcyon] days of the Struggle, when all democrats we were united against a clear embodiment of evil. It was quite disheartening to see the same collective of UDF cadres sitting in the same Wits Great Hall, 30 or 40 years on, still talking rhetorically about breaking the cycle of poverty; freeing the chains that bind our people… And the five foci of the current regime.

But Motlanthe covered this neatly, with a philosophical conceit of history as a continuum:

“Such a trans-historical experience imposes on the current generation, as it does the next, the responsibility to keep alive the vision Amina and her generation set in motion.

“Amina spent her life in a revolution to eliminate Apartheid; our revolution is to ensure that we deliver on the needs of all South Africans in order to change their lives for the better.

“In this connection, the Buddhist saying, ‘If you want to know your past, look into your present conditions, if you want to know your future look into your present actions’, is closer to the mark.”

He added: “While Amina and her generation saw their goals through, the goals of obtaining liberation and ushering in democracy, this in itself does not mean the end of the struggle.”

In this regard, a distinctive aspect of her life stands out: she was a committed anti-Apartheid activist, who passionately embraced the strategic vision of a united, democratic, non-racial, non-sexist and just society.

These tasks speak of a society whose construction is still work in progress today.

So, while the book provides a vivid recollection of the atrocities of the Apartheid era, and an almost voyeuristic depiction of the struggle stalwarts – warts and all – its elegant honesty poses the eternal conundrum of contradiction, of the negative co-existing with the positive – even post-liberation.

This she pithily encapsulates in her description of a visit to Orania. “We were offered melktert, koeksisters, coffee and other goodies and were taken on a tour of the Orania Museum. Behind glass were displays of uniforms worn by various white men and women, and there were guns of every description – big and small – but mostly old and rusted. What horror stories could be told from this exhibition!”

Cachalia had vivid memories of Apartheid atrocities meted out to both her and comrades by the regime under Verwoerd, and “was overcome with nausea and made my way outside to breathe the dusty air of Orania. Then we walked the short distance to Verwoerd’s monument. There on top of a koppie was this tiny statue of the man who had ruled our lives with an iron fist. Madiba stood – a giant – looking down on this wee statue and quipped: ‘I didn’t realise he was so small’. I controlled a burst of laugher by looking around for a distraction.

“Back in the aircraft, I heaved a sigh of relief and whispered to Madiba above the noise of the engine: ‘Never, ever bring me here again’. He threw his head back and laughed.”

Later she reflects on the disjuncture of the day:

“When I got home I reflected on the events of the past 24 hours and I cast my mind even further back. I thought about the momentous years that had passed when I had been part of the struggle. I also remember the time Nelson and I had spent together with Yusuf who was the most important person in my life. But now the personal historical and political times had changed. Or had they?

I asked myself how I, the young activist of years gone by, fitted into the present scene of pomp and splendor. I realised that I had to reconcile myself with the present as this was a new era that was so different from that experienced by my family who had battled tirelessly to improve their lives and overcome the indignity of Apartheid.” And in this tumble of thoughts around the conflation of experiences, Cachalia indeed encapsulates the contradictory emotions and ethical dilemmas posed daily to old-order democrats in the post-Apartheid environment.

And so the memorial somehow achieved its complex objectives of gentle contradiction, and perhaps fulfilled what Cachalia herself would have envisaged. In the elegantly penned speech of Mohlanthe, and in the blunter critiques of following speakers, the memorial served to remind those gathered of how much this country still needs stalwarts of the ilk of Cachalia.

As one grandchild so wittily noted: “Amina has moved on to another life – and there is no doubt she is leading the struggle there already.”

In the words of her other grandchild: “Amina stands as a model for all of us: We need to follow her in the path of ongoing integrity, commitment and honesty.”

As the gathered golden generations of activists flowed out of the Wits Great Hall, some of them were leaning on walking sticks; some were bent over with time; some were sadly not even strong enough to be there. And some were already fighting injustices with Cachalia in another world… The words of Motlanthe resonated:

“Amina Cachalia lived for a higher purpose; she was driven by idealism which, with the dawn of democracy, was translated into a living reality during her lifetime.

“While indeed she is a hard act to follow, pursuing her vision, the vision adopted by her generation is within the realm of possibility for all those who are equally inspired to bring to fruition a better human condition.”

And the admonition: “We cannot afford to fail her, and all those who come before her. We can also not afford to be the generation that failed the future. Our unique challenges are not insurmountable.”

And so the Struggle still continues – aluta continua. Sadly we have lost the living fighting spirit of Amina Cachalia and so many of her generation. Fortunately, however, the memory of Cachalia lives on. And now her own vivid memories do as well. DM

Photo of Amina Cachalia by the Ahmed Kathrada Foundation.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider