Africa

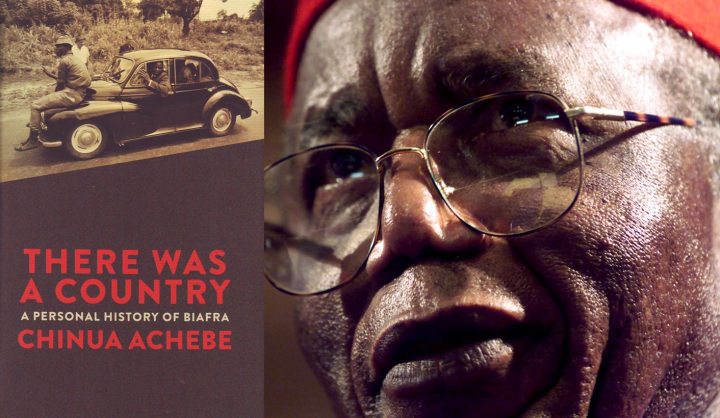

Review: Chinua Achebe on Biafra, finally

It’s taken more than four decades for Africa’s greatest author to talk about his experiences in the Biafran war, still one of Africa’s most tragic – and defining – conflicts. After the long wait, his book There Was a Country was always going to be a little anti-climactic. Still, AGHOGHO AKPOME and SIMON ALLISON weren’t expecting quite as much indulgence.

It was the golden age of African independence. Ghana was free, Guinea was free, then they tumbled one after the other: Cameroon, Senegal, Togo, Congo, Niger, Somalia, Benin, Nigeria, Tanzania, Kenya, on and on. This was the 1960s, when giants of African liberation bestrode the continent with their grand utopian visions. This was the age of Nkrumah, of Senghor, of Nyerere, and a pan-African, socialist utopia didn’t seem so far away.

And then Biafra happened. A little slice of Nigeria, which had borne the brunt of the deadly rivalry between political and military elites, decided it had had enough. It wanted to go its own way, and Biafra was born in 1967, with its own money, flag and capital city. But not so fast – the rest of Nigeria wasn’t exactly pleased with this development, and vowed to restore its British-imposed borders.

The rest is history. Ugly, messy, violent history which set the template for African civil wars and defined how they would be covered. The final death toll was estimated at between one and three million people, many killed by an engineered famine rather than the conflict itself. Multiples of this number were displaced. It was the first televised war, and those familiar, haunting images of starving African babies, of emaciated mothers with hollow, sunken eyes, have their origins here. Biafra was and remains one of the most horrendous manifestations of Africa’s post-independence dystopia.

And with this, the African independence dream was dead.

But that was 43 years ago, and Africa has moved on. So has Nigeria. The Biafran secessionist movement is largely an irrelevance, its one-time leader, the charismatic Odumegwu Ojukwu, is dead. Most of what will be written about Biafra has been.

There was always, however, one outstanding contribution. One man who has kept his silence, who has refrained – with the exception of a single volume of heart-wrenching poems – from expressing himself. That man is Chinua Achebe: one of Nigeria’s most famous sons, Africa’s best-read author, and one-time cultural ambassador for the ill-fated Biafran state.

It is no understatement, therefore, to describe his book detailing his experience and understanding of what happened in Biafra as the most eagerly-awaited publishing event in African history. Finally, after four decades, There Was a Country gives us Achebe on Biafra.

After all the hype, the result is somewhat underwhelming. The prose is quintessential Achebe: graceful, easy to read, and slightly old-fashioned. He’s from a different generation, and it gives his prose a dignity that modern authors struggle to emulate. But it’s also indulgent. By now Achebe has earned the right to write whatever he likes, but a strict editor would still have been a good idea, if only to get rid of the bizarre exclamation marks which litter the text, occasionally and uncomfortably reminiscent of a teenage girl’s Facebook posts.

Negotiating between autobiography, history, politics, religion and cultural studies, Achebe blends reportage, analysis and opinion with extensive telling of his own experiences. It is here that the book is most compelling: when we read about Achebe’s own life, his family’s tribulations, the extreme danger they were all exposed to.

Even after all these years, Achebe’s pain and frustration comes through strongly: he’s still angry about what happened in Biafra, and he’s even angrier about what Nigeria has subsequently become. “Nigeria had people of great quality, and what befell us — the corruption, the political ineptitude, the war — was a great disappointment and truly devastating to those of us who witnessed it,” he writes. This comes as no surprise. Achebe has frequently vented publicly his frustration with Nigeria, and repeatedly snubbed the government’s attempts to honour him with medals and awards.

More surprising is Achebe’s analysis of why Biafra happened, in particular his apparent fixation on ethnic differences in his overarching representation of events and issues. In a sense, it represents an alarming regression to the colonial tendency of explaining away Africa’s internal conflicts as the results of ancient tribal hatreds. It also lacks nuance, and fails to consider the existence of fluid and conflicting definitions. His characterisation of Igboness, Igbo culture, and the idea that Biafran secession was “the decision of an entire people” is especially problematic (the Igbo are one of the three major ethnic groups in Nigeria, and made up the bulk – but not all – of the Biafran state while it existed).

Achebe presumes and projects a homogenous, undifferentiated, and centrally organised political unit, something that did not exist before the war broke out, does not exist now, and has probably never existed. The same holds for his suggestions that Nigerians were (and are) united in harbouring a “common resentment of the Igbo”. This seems unlikely: it is well-known that the absence of any serious form of national unity remains a key cause of the country’s endemic socio-political problems.

“The myth of the tribe is the greatest block to an understanding of Africa by the white world. It makes it impossible for the white world to know and understand what is going on in Africa,” a very wise man once said. That man was Chinua Achebe, and it’s strange to see him revert to that same myth here.

Still, it’s an engaging read, not least because it dredges up all these old problems from Nigeria’s past which are far from being resolved. The book has sparked intense debate in Nigeria, and, thanks to Achebe’s renown, will undoubtedly influence discussions for years to come, and possibly action, on what contemporary Nigerian and African nationalism really means. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider