Maverick Life

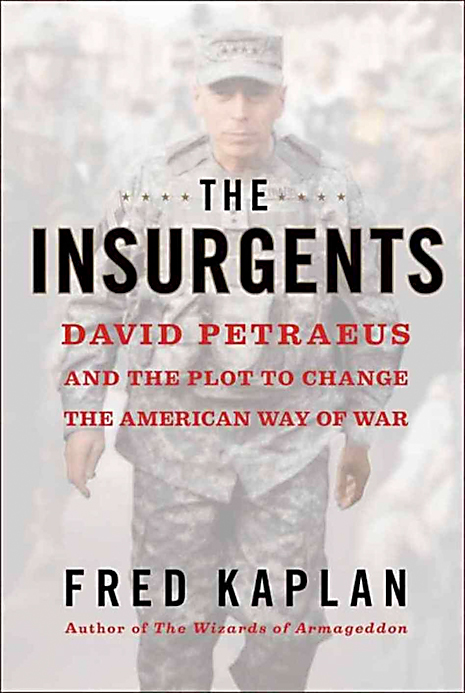

Book review: The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the plot to change the American way of war

Want to know what it takes to win a war in the Middle East? Let me rephrase: want to know what it might take to win a war in the Middle East? This book. By RICHARD POPLAK.

If there is an out-and-out star of Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Fred Kaplan’s essential new book, The Insurgents: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War, it must be the recently disgraced four-star general, who resigned from his post as head of the CIA after it was revealed that he got a little too close with a biographer. The supporting cast is filled out by dozens of heroes and villains, all of whom had a hand, however large or small, in shaping the latter half of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. One of the good guys was a lieutenant colonel named Mike Meese, who did a short stint in South Africa.

His time here helps summarise the difficulties in dealing with counterinsurgency warfare, dubbed Coin in the halls of West Point, where acronyms of that sort are de rigueur. In 1999, Meese was hired as a consultant by the Clinton administration to help the Mandela government merge the Apartheid-era army with the remaining Umkhonto we Sizwe militias. A coherent National Defence Force was never going to be easy, but even by the standards of South African reconciliation, it was proving to be a bitch. Most people assumed the problem was racial – to say nothing of the fact that these two groups had been shooting at each other across the Limpopo only a decade before Meese arrived. But while race is always an issue in these climes, Meese came to realise that the far more serious problem was cultural. The white soldiers were trained in the Anglo-American style of hierarchical structures and rigid fighting techniques. The MK guerillas were steeped in the lean, mean Maoist tradition – quick decision making in a loose power structure. “Integrating the two,” writes Kaplan, “wasn’t so different from integrating regular soldiers and Special Operations forces in the American Army.”

In that short anecdote, Kaplan sums up the challenges facing the many dozens of insurgents – a clever catchall for those trying to change the American Army’s obsession with fighting tank battles against the Soviet Union long after the collapse of the Soviet Union – over the course of the so-called Global War on Terror (Gwot, to West Pointers). The Insurgents is an alternative history of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, played out in Pentagon offices and conference centres and over email, rather than on blood soaked battlefields. This is because Kaplan details an intellectual revolution that developed within the army establishment. It is fought with PhDs rather than Gatling Guns, with PowerPoint, rather than thermonuclear warheads. For instance: “The metrics of success aren’t how many enemy troops you kill but how many townspeople or villagers are spontaneously providing intelligence about where the enemy is (an indication of how much less they’re fearing the enemy and how much more they’re trusting you), how many community leaders openly support the government (and how long such leaders continue to live before the insurgents threaten or kill them), and how much spontaneous economic activity is going on in a town (reflecting the sense that it’s safe to go out on the streets.)”

Now, we must keep in mind that during the early years of the Bush administration, the word counterinsurgency was banned from the lexicon. The incredible delusion that swept through the White House, especially in the first two years of the war, was buttressed by the likes of General Tommy Franks and TK Casey, who were so entirely out of their depth that they assembled a version of events that bore no resemblance to the carnage playing out on the streets of Iraqi (and later Afghani) towns and villages. If Petraeus is the book’s intellectual lodestar, former secretary of defence Donald Rumsfeld is its dunce. Rumsfeld’s conception of American power was encapsulated by the “shock and awe” doctrine – massive doses of pyrotechnics followed by swift ground campaigns. Rumsfeld and his cohorts were working under the long shadow of Vietnam, a war in which an unprepared American army battled insurgents who always had the upper hand. The best way to avoid another Vietnam, so the reasoning went, was to never mount another counterinsurgency campaign.

Flash forward to 2003, and that’s exactly what Rumsfeld had earned after the shock of shock and awe faded. Many of Kaplans’s subjects have starred in their own biographies and profiles – think of The Insurgents as the Avengers of the Gwot, with Petraeus as their Ironman. My personal favourite is an Australian import named David Kilcullen, who was profiled in the New Yorker by George Packer, one of those war journos who was initially bamboozled by Bush administration’s pre-war sophistry.

One of the book’s more gripping sections takes place after Petraeus is reassigned to Fort Leavenworth following his second tour of Iraq. He organises a conference, inviting about 100 disparate voices – Cold War warriors, Coin boffins, army strategists, human rights activists, and reporters – in order to solicit comments on a counterinsurgency field manual he’d commissioned. The manual, romantically titled FM-3-24, Counterinsurgency, fulfilled Petraeus’s long-held dream – to reconfigure the army according to his own intellectual peccadilloes. The manual was premised on a construction that is both tricky and daunting: “the elements of Coin are a matter of multiplication, not addition – it’s ‘military times civilian government times judicial,’ and if one of those factors is zero, the whole is zero.”

There were problems. As anyone who has put a piece of Ikea furniture together knows: manuals are more easily written than followed. There was something antiseptic about how Coin was interpreted in earlier drafts of FM-3-24, Counterinsurgency, encapsulated by one of the participants when he pointed out “there need[s] to be a section on the fighting that goes on in an insurgency war: when soldiers do apply firepower, as well as when they do not.”

Furthermore, where was the army supposed to recruit all the soldiers who were to implement what amounted to a “think first, shoot later” policy of war-making? Was it not asking the impossible of 19-year-old grunts to arrive in a foreign country, quickly come to grips with the social and historical minutia (which in Iraq, one imagines, would require speaking fluent Arabic), figure out how to rebuild and run a bureaucracy – garbage collection, infrastructure repair, health care – all the while identifying and killing genuine insurgents?

And what did “legitimate government” mean in the case of Iraq? Different cultures have different standards when it comes to governance (don’t we know it!), and there was certainly a contingent of Iraqis who thought of Saddam as legitimate precisely because he was brutal and autocratic. How does an occupying army know when they have achieved “legitimacy”? When the weekend markets are full? When Bon Jovi comes to play a benefit concert? When there are only three suicide vests exploding every week? In other words, the manual aimed for benchmarks that were little more than ghosts swirling around an imaginary battlefield.

The case studies cited in the manual read as absurd to several of the attendees. Algeria? That was a brutal colonial campaign that had about as much legitimacy as R200 Rolex. And what did the British in Malaya have to do with a counterinsurgency in the 21st century? The Brits had been in the region for decades before the Malayan Emergency broke out (and was finally quelled in 1960). Many officers spoke not just the local language, but local dialects, and they were able to draw on a network of collaborators that fed them the human intelligence that is arguably the most important weapon in the Coin operative’s arsenal.

Petraeus’s manual described operations for an American force that parachutes into a conflict in virtually unknown territory, and is forced to, well, nation-build. What the manual failed to describe is how that was to be done in a place like Iraq, which is as utterly fragmented – a nation in name only. The unspoken consensus of those opposing the manual was the following: the man the Americans deposed was possibly the only person on earth who could manage “nation-building” Iraq. It didn’t require winning hearts and minds. It required gassing your sectarian enemies. The Iraqi government didn’t want the same thing the Americans wanted. They wanted to settle ancient, and not-so-ancient grievances. And that doesn’t make for a stable partner.

In other words, the manual wasn’t necessarily a rulebook for winning that war, it was a roadmap for transforming the army. Petraeus and his more voluble supporters had to know that their work would have more influence in changing how the military thought, rather than how it behaved on the battlefield. The soldiers on the ground in Iraq who were capable of implementing the manual were already doing so, years before the manual was written, and without the benefit of an overarching methodology.

In what would eventually become an appendix to the FM-3-24, Counterinsurgency, Kilcullen wrote an essay called “Twenty-eight Articles: Fundamentals of Company-Level Counterinsurgency” (a nod to TE Lawrence’s observations), a tip sheet directed at young soldiers to whom all of this was very new. “What does all the theory mean, at the company level?” he asked. “How do the principles translate into action – at night, with the GPS down, the media criticising you, the locals complaining in a language you don’t understand, and an unseen enemy killing your people by ones and twos? How does counterinsurgency actually happen? There are no universal answers, and insurgents are among the most adaptive opponents you will ever face. Countering them will demand every ounce of your intellect.”

Indeed, The Insurgents documents this intellectual revolution in lucid detail. Kaplan has done a fine job of breaking down a history that has not yet played itself out. It’s a vital read for anyone trying to figure out the past decade or so in US military history. And for anyone who hopes to understand what future campaigns may look like. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider