World

The house that Bo built: Taking Chongqing’s pulse after the fall

Almost a year after Bo Xilai, the Chinese princeling involved in the most significant political scandal in China since, well, the Gang of Four were kicked around, the city that personalised his particular brand of neo-leftism awaits a second coming. Chongqing is in a deep freeze; its awakening will offer many clues on the Xi Jinping decade. By RICHARD POPLAK.

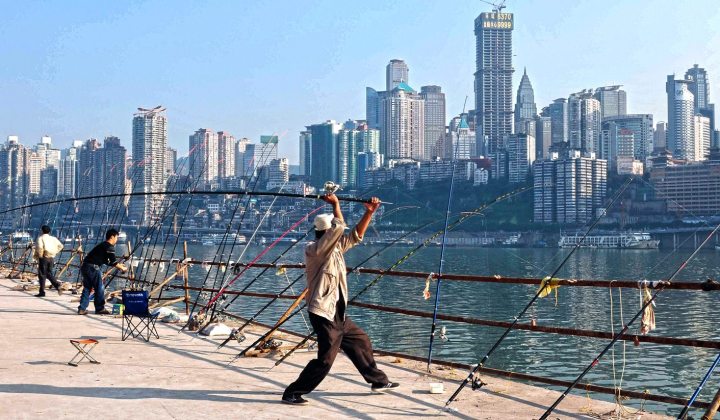

They call it the invisible city. For one thing, Chongqing spends much of the year hunched beneath a thick pillow of fragrant fog, its alleged skyscrapers obscured behind an admixture of moisture and pollution. For another, it’s a municipality of almost 32 million souls – roughly the population of Canada – that gets very little attention. It does not have the awe-tinged cachet of other monstrous metropoli, like Sao Paulo, or, Mexico DF. Even in China, Chongqing plays second fiddle to nearby Chengdu, which locals assure the visitor is “much, much more international”.

But glance at a map of the Middle Kingdom, and note that Chongqing is in the middle of it. With its privileged position on the banks of the Yangtze, Chongqing has long functioned as a river port and a landing spot for the hundreds of river clans that made the region a rich and spirited nexus point. No surprise that Chongqing was, during the Sino-Japanese war, the Kuomintang’s provisional capital. It is also the youngest municipality to come directly under the management of the central government in Beijing – in 1997, it was formed in order to co-ordinate the resettlement of migrants from the Three Gorges area, and to jumpstart development of the western regions. In 2010, it became one of only five so-called “national central cities” to evolve since Deng Xiaoping began the process of decentralisation in 1979.

So Chongqing, then, isn’t properly a city. It’s a power centre. The municipality sprawls over more than 77km², gulping in trading towns, counties, districts and swatches of rural land. The de facto city holds about seven or so million people, and it is a very busy place. But all the activity belies a significant sense of instability – nobody quite knows where the city is going. And it has everything to do with the fall of Bo Xilai, one of the biggest political scandals ever weathered by the Chinese Communist Party, the shockwaves of which have yet to cease battering the city.

“My parents did not want me to come here,” one businesswoman told me. “They fear it is unstable. They want to know what will happen here.” One pervasive theory is that the CCP will punish Chongqing for the sins of its one-time leader. That seems highly unlikely. The government has too much riding on the success of this city– and yet the choices it has made hardly inspire confidence.

What terrifies most people is the return of organised crime, which was the most obvious concern of Bo’s reign as municipal Communist Party secretary. Bo, as the world has come to learn, was the son of Bo Yibo, one of the so-called Eight Elders – a princeling destined to shoot up the party ladder and claim a spot on the Politburo. Unlike so many of the high-ranking party officials, Bo did not, in Deng’s words, “hide brightness, cherish obscurity”. He was loud, he was charismatic and he was charming. He had none of the faux humility of the most garrulous of China’s recent leaders, Jiang Zemin, and certainly none of Hu Jintao’s technocratic forthrightness. He was a populist, who made his name during a successful mayoral tenure in the port city of Dalian, where he and his chief of police, Wang Lijun, cleaned things up and ran a tight ship.

Chongqing was a job of a different order. The city represents a genuine prize – a nominal GDP of $158 billion, with huge companies like Ford and Hewlett-Packard building plants and putting down roots. Like Shanghai, which has always been a standalone power centre, Chongqing promised its leader a smooth run to the top, and perhaps a shot at the presidency.

One of Bo’s first initiatives was to go after organised crime. Chongqing was notoriously crooked, and billions of yuan were siphoned out of the city by the mafia. The crackdown was swift and massive, incarcerating almost 5,000 people, many without trial. Lawyers who claimed that their clients had been tortured were themselves arrested, and the brutality with which Bo and Wang cleaned the city up shocked even Beijing. But what really rattled the good folks at the Great Hall was Bo’s neo-leftist “Chongqing Model” – a strain of development-friendly, populist red capitalism that ensured double-digit growth, but freaked out Bo’s many enemies. They were waiting for a slip, and when his wife murdered English businessman Neil Heywood, it was game over.

What, wonders the citizen of Chongqing, comes next? The post of municipal secretary will have to go to a team player, more likely a member of the Politburo. The city will become even more business-friendly with the opening of another special economic zone, and a second convention centre reportedly being built outside of the clogged downtown. The days of populist Mao-was-awesome sing-alongs is over, and the city will be rebuilt in the Xi Jinping image, whatever that image happens to be. So far, Xi appears to be sticking to the course by favouring large parastatals and crushing any sense of openness. His recent “crackdown” on corruption, always a big problem in Chongqing, is probably political theatre – but that still remains to be seen.

In other words, no one really knows what is happening in the city. One of the world’s largest cities hides under its pestilential cloud, and waits for the future to happen. The stakes are big, the money is large, but Beijing can’t allow another rogue to have his way with the joint. The future is foggy. It’s always been that way in Chongqing. DM

Photo: A man casts his fishing rod into the Jialing River in Chongqing October 31, 2012. Many people have been seen fishing along the river due to the rise in water levels after the Three Gorges hydropower project reached its full water storage capacity of 175 meters during a storage test on Tuesday, local media reported. REUTERS/China Daily

Become an Insider

Become an Insider