World

Thirteen days when Earth stood still – 50 years later

The 50th anniversary of the Cuban Missile Crisis brings both thoughts of a darker time in world history and a renewed sense of caution as we face mounting international pressures. By J BROOKS SPECTOR.

Cuban leader Raúl Castro’s announcement that Cubans will now be allowed to travel freely beyond their island is the latest reminder of the legacy of the 1962 US-Soviet standoff over nuclear missiles in Cuba that nearly plunged the two nuclear powers into atomic warfare 50 years ago this week.

It may seem astonishing now, but throughout the 1950s and early ’60s, children like this writer throughout America, and most probably in the Soviet Union as well, lived with the idea of death. Death in the form of nuclear Armageddon that would be visited on school children foolish enough to fail to follow the instructions in every school’s routine “duck and cover” civil defence drills. The rise and fall of a wailing civil defence siren would sound, children scrambled safely beneath their elementary school wooden desks, heads down, eyes covered to protect against the deadly atomic flash (sometimes peeking through fingers) fearfully watching for the tell-tale flash of the real explosion.

Fear was palpable. Television, radio, newspapers and popular novels frequently offered stories about the atomic holocaust visited upon Earth as Russian and American bombers, missiles and even nuclear-armed artillery duelled for victory in a world where the living would surely envy the dead. Shows like “The Twilight Zone” dealt frequently with the terrors of a post-nuclear war world; films like Dr Strangelove and Failsafe fantasized about the inevitable; while classic science fiction stories like On the Beach, A Canticle for Leibowitz and The Golden Horn set out the new human society that would arise on the ashes of the old – or perish amidst the flames.

A popular story had it that Albert Einstein was asked by a journalist what super weapons would dominate World War III. Einstein answered that while he wasn’t sure about the Third World War, he was absolutely certain the war that came after that one would use sticks, stones, bows and arrows.

The US defence bureaucracy and military establishment – and undoubtedly their Soviet equivalents – were equally transfixed with the emerging nuclear balance, trying hard to create a military doctrine that could explain how one side’s nuclear weapons would be a counterweight to the other’s in a balance of terror in a strategy of deterrence and Mutually Assured Deterrence and Destruction. Each side was intent on stockpiling sufficient weapons that even if its antagonist could carry off a pre-emptive launch of weapons, the other side would still have sufficient forces left over in reserve to deliver a lethal response.

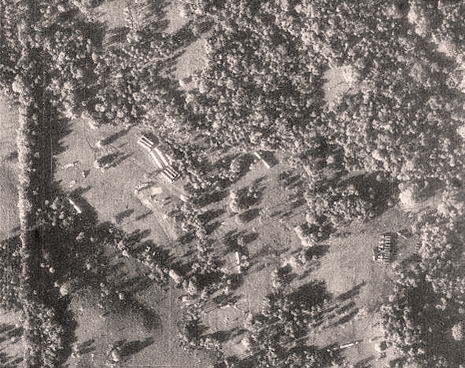

Photo: U-2 reconnaissance photograph of Soviet nuclear missiles in Cuba. Missile transports and tents for fueling and maintenance are visible. Photo taken by the CIA

With that clarified, no rational leader would choose to launch a first strike if it meant their own half of the world became cinders once all the missiles and planes had done their horrible work. For the theorists, the idea, instead, was to create a perfectly protected second strike that could guarantee retaliation and thereby prevent the first strike from ever happening.

Strategists like Herman Kahn and Thomas Schelling developed mathematically sophisticated models of the movement up the escalatory ladder from a modest border patrol clash to a full-scale nuclear war, the better to sort out how to put a break on any run-away military confrontation. Meanwhile, however, the two sides continued to test increasingly terrifyingly sized nuclear weapons and worked on missile delivery systems of increasing accuracy and ease of operation.

But one stubborn question remained. Could one side come up with a weapon that would break this stalemate, providing a first strike capability that would put the other side permanently off balance, thereby creating a decisive strategic advantage that could be used for major geopolitical gain?

In 1960’s American presidential election, one of the electrifying issues that animated the campaign was the supposed missile gap favouring the Soviet Union. Democratic candidate John F Kennedy charged that Dwight Eisenhower’s Republican administration had allowed the Russians to achieve tactical, and perhaps even strategic, success as they built larger, more agile guided missiles in contrast to those developed by the American military. This was paired with the Russians’ success in reaching space with their new rockets. The fear was that a Russian satellite, loaded with a bomb, could pass over the US and launch its payload from space.

Fidel Castro’s increasingly radical socialist revolution in Cuba was drawing closer to a full-scale alliance with Russia at the time, antagonising the Americans. Many in the Cuban middle class began to flee to America, and once there pressed for something to be done to re-establish their one-time control of that island, just 150 kilometres from Florida. In the temper of the times, this had popular resonances with many political leaders in the US.

Early in the his administration, Kennedy, perhaps unnerved by his unhappy first encounter with Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, allowed the CIA to go forward in sending a secretly equipped army of Cuban exiles to end Castro’s rule on the island. This invasion force was defeated at the Bay of Pigs landing zone, but Castro, himself now close to panic over the possibility of a formal US invasion of his island, prevailed upon his Soviet allies to build up their military forces on the island, including the secret installation of batteries of intermediate range nuclear missiles.

These were missiles that could reach most of the territory of the continental US, most of its major cities, many of its primary nuclear weapons bases – all in less time than it would take to prepare to launch America’s own missiles and strategic bombers. Strategic surprise with an actual first-strike capability in the hands of the Russians seemed in place. For Castro, this missile force has also become a shield that will prevent an American invasion. For the Soviet Union this gamble seems poised to achieve strategic success, allowing them to force the Americans to make yet other concessions in Berlin, Southeast Asia, the Mediterranean littoral – almost anywhere – or else.

Then these new missile emplacements are discovered by routine surveillance flights over Cuba by American spy planes. Once military and intelligence analysts were sure they were missiles, the president and his cabinet and staff were briefed.

On 22 October, Kennedy went on nationwide live TV and radio to announce that terrible Russian missiles were in Cuba, with more on the way. He insisted they would have to go. America – almost literally – held its collective breath, then checked out bomb shelters and stocked up on supplies like tinned milk, beans, tuna, biscuits and water. This might have meant the nuclear war a generation of children had spent afternoons under their school desks giggling about. Newspapers rushed out special editions with maps that showed how those Russian missiles could destroy Chicago, New Orleans, New York, Washington, Atlanta and everything in between.

The president ordered troops to move south to Florida in the first steps of an actual invasion force. This was becoming very serious. The navy steamed a flotilla into place to tighten a ring around Cuba, quarantining the island to prevent the arrival of further shipments of missiles and supplies and, it was hoped, to monitor the return to Russia of the missiles already in place. It was called a quarantine, an antiseptic, clinical word, instead of a “blockade”, which could be interpreted as an act of war.

The two sides were moving quickly into unknown territory, like night drills in a dense forest. The wrong turn of phrase, the wrong message, the wrong act, the wrong signal, the wrong twitch and things could go all wrong.

The mythology that evolved out of this confrontation is of steely eyed men in the White House who carefully calibrated quarantine ship placements and Russian transport ship inspections without boarding the enemy vessels. The craftily interpreted messages from Khrushchev to pick the one that gives a way forward out of madness. There is the sly but effective slipping of messages to Russian intelligence via the ABC News UN correspondent in New York City to keep the communication channel open; and then a quiet backhand agreement to give a tacit pledge not to invade Cuba.

These steps were coupled with a promise to dismantle older American missiles based in Turkey and Italy aimed at Russia, making it easier to climb back down that ladder of escalation and away from nuclear disaster. The world breathed again as then-Secretary of State Dean Rusk said, on 28 October 1962, “We’re eyeball to eyeball, and I think the other fellow just blinked.”

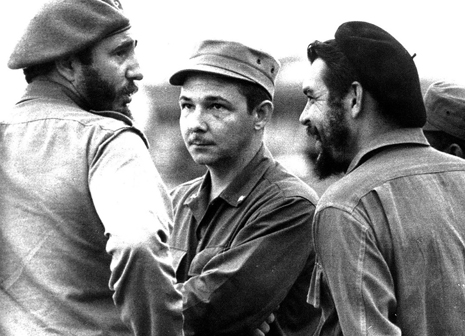

Photo: Cuban leadership: Fidel Castro, Raul Castro and Che Guevara

The standard version is canonized by the Robert Kennedy memoir, Thirteen Days, a movie of the same name and hundreds of academic studies that make use of the Cuban Missile Crisis as the definitive test case of Cold War resolve, tempered by flexibility and a willingness to compromise tactically to the benefit of broader strategic success. Entire university courses are built around the crisis as a case study in political management. Even now, conferences in honour of the crisis’ 50 anniversary, lectures and yet more books are coming forward.

But Cold War historian Michael Dobbs has recently argued that “the myth has become a touchstone of toughness by which presidents are measured. Last month, the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, called on President Obama to place a ‘clear red line’ before Iran just as ‘President Kennedy set a red line during the Cuban missile crisis.’” Dobbs has learned that the Russian ships did not in fact continue ominously to steam towards the quarantine line in the Caribbean Sea.

Instead, “acting to avert a naval showdown, the Soviet premier, Nikita S Khrushchev, had turned his missile-carrying freighters around some 30 hours earlier…. (And) there is now plenty of evidence that Kennedy — like Khrushchev — was a lot less steely-eyed than depicted in the initial accounts of the crisis….” Rather than this clash of the titans, the real dangers came from the more mundane fog of war. Those unknowns and unknowables. “As the two superpowers geared up for a nuclear war, the chances of something going terribly wrong increased exponentially.”

By 27 October, Dobbs argues, the two national leaders were no longer the total masters of their respective military machines now sliding onward under their own momentum. “Soviet troops on Cuba targeted Guantánamo with tactical nuclear weapons and shot down an American U-2 spy plane. Another U-2, on a “routine” air-sampling mission to the North Pole, got lost over the Soviet Union. The Soviets sent MiG fighters into the air to try to shoot down the American intruder, and in response, Alaska Air Defence Command scrambled F-102 interceptors armed with tactical nuclear missiles. In the Caribbean, a frazzled Soviet submarine commander was dissuaded by his subordinates from using his nuclear torpedo against American destroyers that were trying to force him to the surface,” Dobbs writes.

He concluded that “in deciding how to respond to Khrushchev, Kennedy was influenced by his reading of The Guns of August, Barbara W. Tuchman’s 1962 account of the origins of World War I. The most important lesson he drew from it was that mistakes and misunderstandings can unleash an unpredictable chain of events, causing governments to go to war with little understanding of the consequences.” Dobbs warned that this was the lesson presidents Johnson and Bush should have considered as they contemplated what to do with Vietnam and Iraq, “and one that remains valid today.”

Left unsaid by Dobbs, but just as clearly true, is that this very same lesson will need to be understood by whoever takes charge of the US military forces on 20 January 2013. DM

Read more:

- “The Price of a 50-Year Myth,” on the New York Times

- “Lessons from the Cuban Missile Crisis, Then and Now,” a forum at the Harvard University Institute of Politics

- “Pentagon Estimated 18,500 U.S. Casualties in Cuba Invasion 1962, But If Nukes Launched, ‘Heavy Losses’ Expected, on the George Washington University National Security Archive

Main photo: Khruschev and Kennedy meet at Geneva in June 1961.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider