Maverick Life

Found in translation: Mo Yan wins literature Nobel

The 2012 Nobel Prize for Literature has drawn almost as much attention onto the translator as it has onto the writer. What does this say about the cultural gap between West and East? More importantly, does Mo Yan’s win signal a new dawn in world literature? By KEVIN BLOOM.

The story goes that Isaac Bashevis Singer, winner of the 1978 Nobel Prize for Literature, spent much of his writing career moaning about his translators. Which was an unfortunate thing for his translators, but could have been even more unfortunate for Mr Singer. He wrote in Yiddish, a language whose speaking population had been decimated by the Nazis and whose remaining ultra-religious adherents didn’t much care for the heresies that marked his work (for instance, that love affair between the Jewish man and the shiksa woman in his 1962 masterpiece, The Slave).

“There is no such thing as a good translator,” Singer once said, seemingly oblivious to the likelihood that his readership would have peaked in the low double digits – including friends and family – had this long-suffering literary caste refused to indulge him. “The best translators make the worst mistakes.”

Still, as a man named Howard Goldblatt observed a decade after Singer’s death, the Nobel win appeared to confer on the writer a measure of magnanimity. Seems that post the decision of the Swedish Academy to bestow upon him his profession’s greatest honour, Isaac Bashevis Singer took to calling translators “the very spirit of civilisation”.

So who is this Goldblatt fellow and what inspired him to highlight such a blatant hypocrisy? Funny you should ask. You’d think, given the hues of his surname, that the translation of books from Yiddish into English was his stock-in-trade, and that sometime in his career he sustained a wounding blow from the old master. But you’d be wrong. No, Howard Goldblatt is the world’s pre-eminent translator of books from Mandarin into English, and he was making the point about Singer so as to give added heft to a larger point.

“I count as friends a few novelists whose work I’ve translated from the Chinese,” he wrote in 2002. “In part that is a result of the trust the authors – few of whom read English – have placed in me, and in part it is due to their willingness to deal with inevitable queries regarding difficulties, even errors, in their texts. Mo Yan, for instance, whose Red Sorghum brought him international recognition in the early 1990s, is one of those gracious individuals who sings the praises of his translator as often as his translator sings his as a novelist.”

On Thursday afternoon, 11 October, Mo Yan was named by the Swedish Academy as the 2012 winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature, and Goldblatt featured prominently in many of the news items that delivered the announcement. What was odd about this was not that the award had been given to a translated non-Anglophone (as the recent history of the prize suggests, English-language writers are now more of a long-shot than ever), but that there was an implied assumption of a “partnership”. Chinese literature, the subtext hinted, is so far removed from the Western paradigm that the job of the mediator is as important as that of the creator.

Is this true? Or, to be specific, is it more true of Chinese authors than, say, Yiddish ones?

John Updike, had he been alive to watch himself not win the Nobel for another year, certainly might have said so. Reviewing a pair of Chinese novels for the New Yorker back in 2005, he complained that the form had “no Victorian heyday to teach it decorum”. One of the novels on Updike’s desk was Mo Yan’s Big Breasts & Wide Hips, which he described as “a groaning table of brutal incident, magic realism, woman-worship, nature description and far-flung metaphor.” In speaking of Goldblatt’s task, he used words like “exertions” and “midwifery”. His ultimate pronouncement on the book’s use of imagery – which, from another writer, is always an ultimate pronouncement on the book itself – was that “(such) surplus energy of figuration attests to, if not greatness, a greatly ambitious reach.”

Updike was of course an undisputed champion at the sport of damning with faint praise, and so his takedowns, unexpectedly vicious as they may have been (kind of like a belated kick-in-the-head after a nice bottle of rice wine), were best stripped to their essentials – he didn’t fancy the writer, only one man’s opinion.

And the handiest place to go for one’s own opinion of Mo Yan, as thousands of English-speakers did yesterday, is the website of the literary magazine Granta, where an extract from his novel Frog was posted in August.

The story follows Aunty, who is explaining to the narrator how she came to marry the sculptor Hao Dashou, a turn of events that has saddened the family. As Updike remarked of Mo Yan’s earlier novel, it is likewise packed with brutal incident (tens of thousands of frogs attacking Aunty and covering her in a substance that she takes for either urine or semen), magic realism (more frogs, some hanging by their mouths to the lobes of her ears) and nature description (see: frogs). But the metaphors are not what this reader would call “far-flung” – they are unusual, charming and strong.

To wit, the image of Hao Dashou sitting quietly at his workbench, “eyes glazed over and a blank look on his face, like a dreamy old horse. Did all master artists turn into dreamy old horses once they became famous?” Or the description of the multitudinous variety of aggressive frog: “Some were jade green, others were golden yellow; some were as big as an electric iron, others as small as dates. The eyes of some were like nuggets of gold, those of others, red beans.”

Mo Yan is clearly a whimsical writer, a maximalist and an allegorist, which is not everyone’s cup of tea. But he’s also a historical and political writer, a combination that allows him to chide the Communist Party and yet remain a free man. Frog is essentially a critique of China’s one-child policy, a topic that’s no longer as controversial in the People’s Republic as it once was – it’s been said of Mo Yan in this regard that he knows exactly where the line is, and how to come close without stepping over.

The difficulty of pigeonholing Mo Yan more precisely is reflected in how news of his win was reported differently in China and the West. Xinhua and Chinese state media called him the “first” Chinese national to be awarded the Nobel; Western media called him the “second,” after Gao Xingjian, who took it in 2000, and whose work is banned in his native country (Gao has been living in France since 1987).

But however you do the math, Mo Yan could well represent a new dawn in world literature. As Goldblatt recently stated: “China has been behind the curve on promoting and funding translations of its literature in foreign countries by native speakers in those societies. The US, some European countries and Japan actively fund literary translations and help to get them in the hands of domestic readers. China ought to do much better than it has so far.”

That those words appeared in the state-backed China Daily, where Goldblatt went on to say that winning the Nobel is for the Chinese population a matter of “national validation,” means the People’s Republic could soon be exporting its literature as effectively as it does its consumer goods. DM

Read more:

- Interview with Howard Goldblatt, on China Daily

- “Frogs,” on Granta

- “Bitter Bamboo,” on The New Yorker

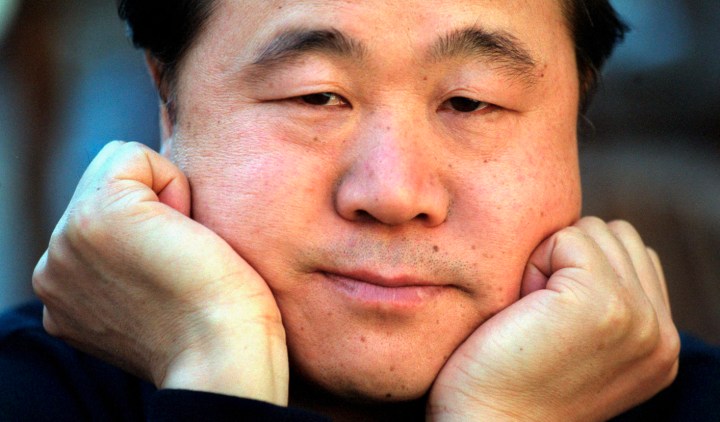

Photo: Chinese writer Mo Yan, in Stockholm, Sweden in this May 2001 file photo. Mo won the 2012 Nobel prize for literature on October 11, 2012, for works which combine “hallucinatory realism” with folk tales, history and contemporary life in China. Mo, who was once so destitute he ate tree bark and weeds to survive, is the first Chinese national to win the $1.2 million literature prize, awarded by the Swedish Academy. REUTERS/Peter Lyden

Become an Insider

Become an Insider