World

150 years later, Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation remains a milestone

America’s Emancipation Proclamation, issued a century and a half ago, marked not only the end of slavery in the US but a strategic shift that assured the country would become a unified nation as opposed to a confederation of distinct states. By J BROOKS SPECTOR.

It is a pleasant two-hour drive from the Washington, DC, area to the rolling hills of the Antietam Creek battlefield, site of the single bloodiest day in the American Civil War. The battle, on 17 September 1862, resulted in a virtual stalemate, although the Confederate (Southern) Army was forced to retreat across the Potomac River and abandon its first effort to carry the war to the North. Northern Union forces, on the other hand, were so exhausted by the furious battle that commanders chose not to pursue their similarly exhausted enemy further.

Five days after this relatively inconclusive battle, on 22 September 1862 – 150 years ago – President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, announcing the end of slavery for all slaves in Southern states then in rebellion against federal authority. In concrete terms, of course, the Union’s rule of law did not extend to those Southern states. Nevertheless, by taking this step, Lincoln dramatically recalibrated the goals of the Northern effort. Now the war aim was no longer just the reestablishment of national authority over the entire country. To that somewhat abstract cause, something else had been added: the final abolition of slavery on American soil.

As The New York Times summed up the impact of the battle, “the bloodiest day in American history, rebuffed the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia’s first invasion of Northern territory, convinced European nations to withhold recognition from the Confederacy, assured Republican control of the House of Representatives in the upcoming midterm elections, gave Abraham Lincoln political cover to announce the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation and finally persuaded the president that the Union could no longer afford Gen. George B McClellan.”

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation thereby turned the war into something that increasingly approached the texture of a national crusade. It gave the war the crucial moral centre of the abolition of slavery as a just, transcendent cause, rather than just an argument over whether the United States was a single nation with one legal identity, or essentially a free, voluntary association of independent states with two competing economic systems.

Lincoln’s proclamation read in part, “That on the 1st day of January, A.D. 1863, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.”

In reporting on the battle and the proclamation’s anniversary commemorations, The Washington Post noted that “The Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation – which declared Jan. 1, 1863 the date when African Americans held as slaves in any part of the Confederacy that continued the war effort would be considered ‘forever free’ – may have been meant as an announcement of future action, but to many enslaved people it was an invitation to liberate themselves immediately…. But for all the lofty talk in Washington, the cold reality was that no plan was in place to care for the thousands of slaves who would run to the safety of Union military camps on Jan. 1, or any day before that. Thousands did indeed begin their trek to freedom well before the end of the year and arrived wearing tattered clothes and weak from hunger, quickly overwhelming any services the military could offer.”

Readers who recall the film Glory and its portrayal of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment (the iconic all-black military unit) may also remember those graphic scenes of newly manumitted African-Americans being turned into itinerant camp followers and pawns of military raiders as growing areas of the South came to be occupied by Northern armies.

The paradox within this proclamation, of course, was that it was a careful political compromise coexisting with a deeply moral act. The proclamation only called for the ending of slavery of those living in Southern states then in rebellion – precisely where the Union’s legal writ did not run – and delayed any decision on slavery in those states still legally permitting slavery to exist but which had not declared their independence from the Union.

The rationale for that exemption was simple, if morally anomalous. Lincoln and his advisors had concluded that freeing slaves in Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, Missouri and the newly separate state of West Virginia might lead to such dissent in those states that the political leadership class there might even reconsider their decisions to stay loyal to the Union. Or, at a minimum, they might choose to impede further military progress towards re-conquering the rebellious South.

What it did do, of course, was to ensure that as increasing areas of the South came under Union control through battlefield victories, more and more of the South became areas where slavery no longer had legal sanction to exist. However, it took the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the US Constitution to decisively end slavery, bar any future abridgement of the rights of any citizens by virtue of previous condition of servitude and end race as a legal bar to voting rights. These amendments were ratified successively in 1865, 1868 and 1870 – after the Civil War had ended in spring of 1865. Once the Northern occupation of the South ended in 1876, however, segregation and racialised oppression returned to the South in both de jure and de facto forms – a set of circumstances not decisively broken down until the civil rights revolution of the 1960s.

Another important element of this proclamation was that it authorized the enlistment of free African-American, now-former slaves into the army and navy, saying, “And I further declare and make known that such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” As manpower needs grew ever more rigorous during the war, more than 200,000 black troops enlisted, contributing significantly to the North’s decisive manpower advantage and its ultimate military victory.

In yet another way, the Emancipation Proclamation changed the texture of the war. With the abolition of slavery now an explicit war goal, it made international support for the South synonymous with support for a continuation of slavery, thereby making it less and less palatable for officially anti-slavery nations like France and England to support the South. Ironically, however, the proclamation and its declaration of the end of slavery as an explicit war aim also triggered several days of serious rioting in New York City, as would-be inductees into the army – mostly new immigrants from Ireland – fought pitched battles with troops in the summer of 1863, fearing they would be fighting for the freedom of people who would then be competitors for jobs and generating downward wage pressure in the process.

Historian John Fabian Witt also argues that the proclamation achieved another important result: it changed the nature of property rights in warfare, transforming the international laws of war. Witt writes that the proclamation “created the rules that now govern soldiers around the world… (as it led directly to a set of military orders that) set out a host of humane rules: it prohibited torture, protected prisoners of war and outlawed assassinations. It distinguished between soldiers and civilians and it disclaimed cruelty, revenge attacks and senseless suffering. Most of all, the code defended the freeing of enemy slaves and the arming of black soldiers as a humanitarian imperative, not as an invitation to atrocity. The code announced that free armies were like roving institutions of freedom, abolishing slavery wherever they went.”

This Emancipation Proclamation finally put the US national government squarely on the side of the complete abolition of slavery, a process that internationally had gained much of its initial impetus – and concrete impact – from the ideas of the French Revolution and then the English abolition movement led by William Wilberforce that achieved its final victory in 1833. America’s decision actually came more than a decade after the end of legalized serfdom in Czarist Russia.

After America’s abolition of slavery, save for more shadowy circumstances in parts of the Middle East and Africa, Brazil stood out as the only major nation where slavery continued to remain legal for millions until that country abolished the practice in 1888. The fight against slavery is not entirely over, however. In recent years, a new abolition movement has come into being as an international effort to bring an end to the slavery-like conditions still endured by people in parts of Africa and Asia where lifelong indentured labour conditions continues to exist, despite global outrage. DM

Read more:

- “Another side to emancipation,” on The Washington Post;

- “Emancipation Proclamation, 22 September 1862,” on CivilWarInteractive.com;

- “America’s Bloodiest Day,” on The New York Times;

- “150th Anniversary of the Battle of Antietam,” on the National Parks Service.

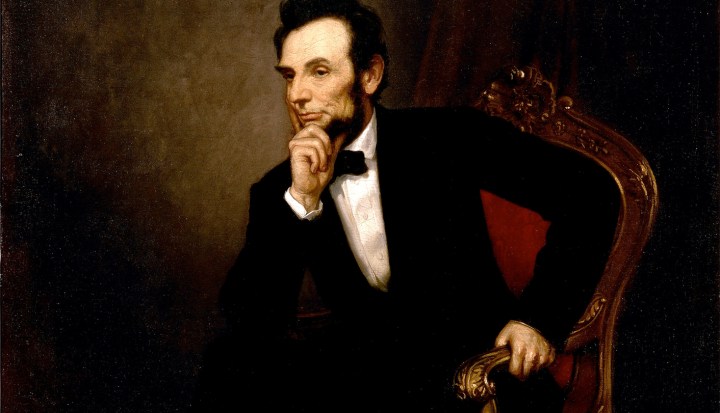

Photo: Abraham Lincoln (Wikimedia Commons)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider