Africa

SA plays nicely with ‘pariah state’ Eritrea

South Africa, unlike most of the rest of the world, is very nice to Eritrea; nice enough to host its foreign minister and exchange a few meaningless diplomatic pleasantries. This is more than the little east African country—also known as a ‘pariah state’ —is used to, and cements South Africa’s place as one of their most important allies. By SIMON ALLISON.

In one of South Africa’s least exciting diplomatic encounters this year, Eritrean foreign minister Osman Saleh Mohamed was entertained in Cape Town by his South African counterpart, Maite Nkoana-Mashabane.

For South Africa, it was a pro-forma meeting. Staffers at Dirco told the Daily Maverick that it was a non-event as far as they’re concerned, just another stop on the diplomatic merry-go-round that must be observed with due protocol to ensure no one’s feelings get hurt. Besides, we got what we wanted from Eritrea recently, namely their vote for Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma in the African Union Commission Chairperson elections. That’s about as useful as the tiny, belligerent east African country is ever likely to be.

That’s not to say there wasn’t anything worth discussing. The agenda should have been dominated by the death of Ethiopian Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, which has the potential to alter the political dynamic in the horn of African significantly. It could have been supplemented by a frank talk about Eritrea’s reported connections to Islamist militant group Al Shabaab in Somalia. The United Nations has accused Eritrea of arming Al Shabaab.

Instead, what we got was a bland statement from the minister and a meaningless agreement: “In order to further enhance our bilateral relations, we have signed a Declaration of Intent, which records our mutual intention to work towards enhancing bilateral relations,” said Nkoana-Mashabane.

For Eritrea, the official visit—officially aimed to enable discussions on “a range of issues of mutual interest”, whatever those might be—is of somewhat greater importance. South Africa is one of Eritrea’s largest trading partners, and one of their few friends in a world which has largely rejected the country as a result of its poor governance record.

This record is worth further examination. Here are the lowlights, according to Human Rights Watch: “Eritrea is one of the world’s most repressive and closed countries. The government of President Isaias Afewerki has effectively banned the independent press. Journalists languish in detention, as do officials who question Isaias’s leadership; many have died in jail. No civil society organisations are allowed to exist. Arbitrary arrest of citizens is rampant, and torture in detention is common. Leading religious institutions—Orthodox Christian and Muslim—are run by government-appointees; adherents of other religions are jailed until they renounce their faiths. Nearly all men and many women over 18 are conscripted into indefinite ‘national service’, which exploits them as forced labor at survival wages.”

This domestic situation has complicated Eritrea’s relationship with the outside world (although it hasn’t given the South African government much pause; we are used to laying out the red carpet for tyrants and dictators).

Eritrea’s natural partner, both culturally and geographically, is Ethiopia, but the two countries hardly talk to each other. It’s hard to blame the Eritreans for this; the current administration is made up of veterans from the long and bloody—but ultimately successful—liberation struggle against the imposing Ethiopians, and from the just as bloody Ethiopia-Eritrea war from 1998-2000 that followed Eritrean independence in 1991.

Eritrea’s resentment is so deep that its entire foreign policy is predicated on the idea that “the enemy of my enemy is my friend”. In this case, the enemy is Ethiopia and the “friends” are a small, motley assortment of countries and organizations, including Islamist militant group Al Shabaab in Somalia, which the United Nations accused Eritrea of supplying arms to, and Qatar. Countries like the USA, the UK and China are unpopular in Eritrea’s capital Asmara thanks to their proximity to the Ethiopian government.

South Africa, on the other hand, enjoys no such proximity—indeed the relationship has been fraught recently over Dlamini-Zuma’s election. Ethiopia was firmly in the Jean Ping camp, understandably annoyed that South Africa has broken the unwritten rule preventing big countries from fielding candidates. This might explain Eritrea’s enthusiasm for our country, which translated into an unprecedentedly warm reception for South African Ambassador Iqbal Jhazbhai, who took up his post earlier this year.

“I was quite surprised,” Jhazbhai told the Daily Maverick in an interview in May. “They say the president only accepts credentials of ambassadors once a year. I arrived in Asmara in the middle of March and I was hardly there nine days when I was told, ‘The president wants to receive you.’ I met the Chinese ambassador afterward and he said to me, ‘You’re very lucky. I had to wait six months before I was officially received. You must be Superman.’ And I replied, ‘No, I think it’s the super country I’m from’. So I think it shows willingness from [Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki] to engage us.”

Eritrea could use a bit of engagement. Its isolation, much of it self-imposed, has left its economy in a dire state. GDP per capita is just $700, one of the lowest in the world (compare that to South Africa’s $11,100). A largely unskilled population and an inability to produce anything that the rest of the world wants to buy has left the government, which has a less than stellar reputation of managing the resources it does have, with an impossible task in terms of dragging the country out of poverty. It is a task complicated further by the international sanctions targeting individuals and entities with links to the government.

The one thing Eritrea has produced a little of in recent times is gold, a find which has spurred its economic growth to an almost unbelievable 17% last year. This is not as impressive as it sounds given the tiny base from which this is calculated; still, it’s an improvement and has given the government a little money for infrastructure projects.

South African companies have started sniffing round the mining concessions, hoping for a bit of the action. AngloGold Ashanti in particular has been active, having purchased a couple of exploration blocks which are still in the process of being analysed. The South African mining sector’s involvement, and the capital expenditure which it entails, helped to boost South African exports to Eritrea to over R200-million in 2010, mostly mining equipment. This is a massive sum in Eritrea, dwarfing American and European exports.

But for South Africa, it is small change—exports to Kenya are 50 times that. And Eritrea remains small fry as far as our diplomats are concerned, no matter how important we are to them. DM

Read more:

- Eritrea: Africa’s North Korea, complete with unhinged president on Daily Maverick

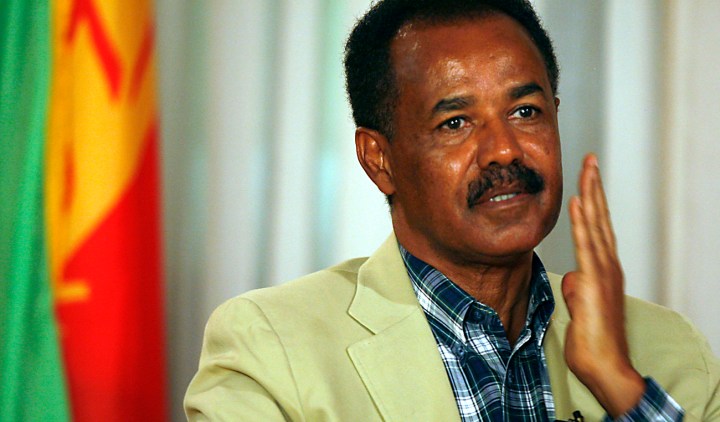

Photo:Eritrea’s President Isaias Afwerki gestures during an interview in Asmara May 13, 2008. (REUTERS)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider