Maverick Life

Paulo Coelho, Amanda Hocking, and social media’s great publishing lie

On the back of Facebook’s disastrous IPO, more and more pundits are predicting the imminent pop of the social media bubble. With few industries having become as bloated by this bubble as self-epublishing, the fallout is likely to cast aspersions on one very famous author—and not, it seems, the author you’d expect. By KEVIN BLOOM.

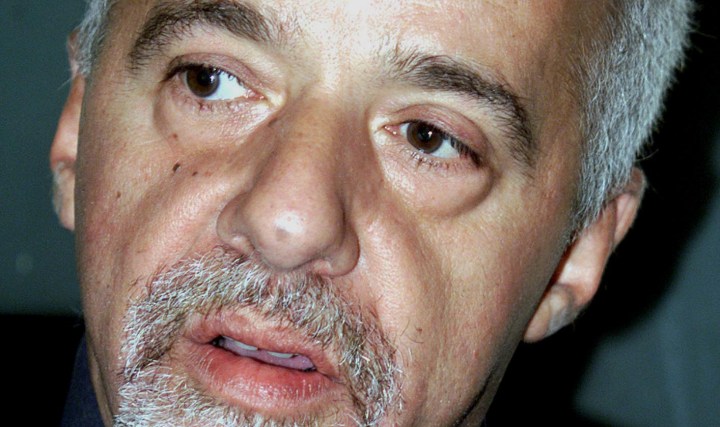

Paulo Coelho? Yes, you’ve heard of him. He’s the guy with 5.14 million Twitter followers. The dude who simply brands himself “writer” (with a small “w”) and lists his location as Rio de Janeiro. The guy whose most famous book, The Alchemist, sold 65 million copies worldwide and whose Tweets—currently numbering more than 16,000—tend towards the spiritual and the aphoristic. For instance: “The reward of our work is not what we get, but what we become.”

Anyway, that was the insight in the early hours of Tuesday, 31 July. On an otherwise unremarkable day in September last year, it was this: “When your legs are tired, walk with your heart.” Which was the very Tweet that got the New York Times to label Coelho, in a supremely switched-on and clever turn-of-phrase, a “sort of Twitter mystic”. The writer, it seemed, was the epitome of what social media could be—a universal peddler of influence for the Greater Good.

It was somehow appropriate, therefore, that Coelho would be the man to facilitate a “boot camp” for aspiring e-authors, wherein he would teach anyone who paid a not-insignificant fee how to give away their books online, an extension and a practical application of his personal philosophy of “self-piracy”. The logic of the course was that the old model of protected content was dead, that authors needed to internalise and embrace this higher truth, and that the surest way to build a future fan-base was to accept the open transcendence of the Web in the here-and-now.

However, as novelist Ewan Morrison noted in the Guardian on 30 July, Coelho neglected to apprise his paying devotees of a few key facts:

“[He failed] to mention that he made his millions in mainstream publishing in its heyday, or to explain that he carried his existing fan base with him on to the Net, so he isn’t actually a verifiable example of building a Net platform. He also seems to have overlooked the likelihood that if he had given his books away over the last 40 years, he would never have been able to build the career that he now enjoys.”

Morrison, of course, wasn’t writing about the apparent hypocrisy of Coelho per se—for another, less healthily reimbursed author to do so would too blatantly reek of sour grapes. No, he was taking a sideswipe at the guru to make a larger point. His article, entitled “Why social media isn’t the magic bullet for self-epublished authors”, was written in the spirit of an all-encompassing exposé.

Question is: what’s to “expose” about the fact that social media isn’t the answer to the prayers of wannabe authors? Surely everybody knows that? Are there really people out there who believe that thanks to the wondrous equalising powers of modern technology, all they have to do is master Twitter and Facebook, give away a few of their books for free, and soon they’ll be the next Amanda Hocking?

Seemingly, there are. The problem, apart from the obvious—the New Age promise that everyone has inside them a “novel waiting to get out”; the fantasy of working on the “sequel” to said novel from your yacht, while simultaneously quaffing canapés and bellinis—is Hocking herself.

In 2010, as the now legendary story goes, this 27-year-old group home worker from Austin, Minnesota, frustrated at the piles of rejection letters that had been building up from traditional publishers—in her spare time, she had written 17 novels in the genre of “paranormal young adult fiction”—turned in desperation to Amazon, and specifically its relatively new self-epublishing option.

By March 2011, she’d sold more than 1-million copies of nine of those books and earned $2-million from sales, statistics that set her up as the figurehead of the digital publishing revolution. As with Coelho, what wasn’t immediately clear to the would-be copycats were the years she’d spent honing her craft. The difference between Hocking and Coelho, however, was that the former used her wealth and fame to concentrate on being a full-time writer. She was just never that into cashing in on her digital publishing kudos.

And here, according to Morrison, may be why: “The bad news for social media companies is that after all the hype and the projections, there are stats: there is evidence, there are consequences and heads will roll. In publishing terms it has recently been revealed that 10% of all self-epublishers make 75% of all the money; that 50% of self-published ebooks make less than $500 a year …. and that 25% [don’t] cover the costs of production. Broadly, what this means is that if you went out on the street with a book in your hand and tried to sell it to a stranger… and you did this every day, you would still be making more money than 50% of all self-published authors on Amazon and all the other new epub platforms.”

By “social media companies” and the “bad news” they were facing, what Morrison meant was both intuitively simple and devastatingly portentous. All those “electronic publishing experts” claiming that authors should spend 80% of their time Tweeting versus 20% of their time writing? The legions of “online promotions specialists” offering to post glowing book reviews on Amazon for a small fee? They were, he predicted, about to be rendered obsolete by the next bursting bubble.

Needless to say, the Facebook listing in May of this year, an event Bloomberg termed the “worst IPO of the decade”, had a lot to do with Morrison’s prophecy. Social media, it seems, isn’t the selling tool it was supposed to be. In June, a Reuters poll revealed that four out of five Facebook users have never bought a product or service as a result of advertising or comments on the social network site. And in February, months before the IPO, a study by independent research house eMarketer suggested that Facebook could not compete with email or direct-mail marketing when it came to influencing consumers’ decisions.

Implying, if you’re an aspiring e-author, that all the Facebook “likes” in the world aren’t going to make you the next Paulo Coelho. Because only if you are already Paulo Coelho will you have a large enough social media following (in his case, Twitter followers) to generate worthwhile sales, and you only get to be Paulo Coelho if you’ve already generated previous sales via other, non-social media methods.

As for Hocking, the anomaly continues to fill unpublished writers with hope. And the parasite industries that feed on this hope continue to trot out their easy-to-master wisdoms: Why spend all day learning how to become a writer, when what you should really be doing is building a platform on Facebook?

When, as appears increasingly likely, the social media bubble fully bursts, it will be fun to watch these leeches slink back into their swamp. Maybe then we’ll get another mystical insight from Coelho: “When your legs are tired, slither on your belly.” DM

Read more:

- “Why social media isn’t the magic bullet for self-epublished authors,” in the Guardian

- “Best-Selling Author Gives Away His Work,” in the New York Times

- “The Social Media Bubble has popped,” in thenextweb.com

Photo: Paulo Coelho (Reuters)

Become an Insider

Become an Insider